After World War II, neo-realism sprung up as a film movement; films about everyday people struggling with the new realities of the world around them, a counter-movement to the big, glossy, Hollywood productions. These films were often shot on location and frequently featured non-professionals. To me, the movement reached a pinnacle with De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves.

Kurosawa had presaged this movement to an extent with The Most Beautiful. But in 1947, relatively free from restrictions, Kurosawa looked at the realities of post-war Japan for the first time with One Wonderful Sunday, a contemporary film that combined the post-war concerns of a film like The Best Years of Our Lives with the simplicity and intimacy of a film like Before Sunrise.

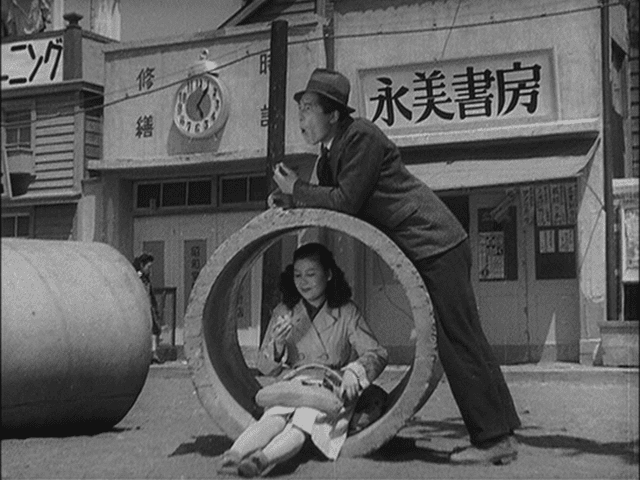

Like Before Sunrise, the setup of the film simply involves an extended date. A man, Yuzo (Isao Numazaki), meets his fiancée, Masako (Chieko Nakakita), on their only day off. He’s a veteran who’s struggling to get by in the devastated post-war economy and the two can’t afford a place where they could live after marrying. Between the two, they have 35 yen to somehow pay for a day together. What follows is a series of episodes involving their day together which explores the harsh realities of contemporary Japan and the strain it’s putting on their lives.

Kurosawa pulls very few punches with the exception that the American occupying force is absent from the movie. What’s there gives the film an edge even today, and the title of the movie certainly comes off as ironic for a good portion of the run time.

To start off, the couple looks at a cheap model home that only costs 100,000 yen. Even at that cut rate price, the dream of owning a home seems impossible. They learn of a cheap but awful apartment and rush off to see it. They’re warned off by the former tenant, now working off his debt to the landlord by being the property custodian in a funny scene as the custodian changes his sales pitch depending on the presence/absence of the landlord. Despite the apparent awfulness of the place they strongly contemplate the prospects of at least being able to live together, but quick calculations show the impossibility of even that modest dream. They had dreamed of being able to open a café together, but they can barely afford their own existence at present.

The power of dreams is one of the recurring themes. Kurosawa introduces it early. Of what use are dreams in the face of such a devastated reality? That’s one of the central questions of the movie.

Discouraged, Yuzo attempts to join a street ball game with the area kids as a momentary respite. Complete with western music playing on the soundtrack, in this case Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star, it’s fun and a rejection of pre-war feudalism. And it lifts the spirits, until Yuzo hits a ball into a nearby food stand costing a few precious yen for some damaged rolls. Even playing has a price to be paid.

Yuzo recalls that one of his army comrades, one he doesn’t particularly like, owns a cabaret and Masako encourages him to go visit. Ironically, Yuzo never gets to meet his army companion. Instead, he’s mistaken for a gangster asking for protection money and lead into the bowels of the club. It’s an outstanding sequence with a tracking shot that presages the iconic steadi-cam shot from Goodfellas.

After a few brief moments of interaction with the lowlifes present, he’s handed an envelope of money and it dawns on him how people perceive him. The corruption around him is ever present and everyone assumes the worst, probably with good reason. And despite his need, Yuzo walks out in disgust without the money as he still has his honor and wants no part of the Black Market or racketeering. It’s the first real statement of principles in the film, although subsequent events will show that Yuzo isn’t a saint or immune from failings. Without really having to state the theme, Kurosawa asks how one can survive in the world and maintain one’s honor?

Searching for anything cheap to do, the couple heads to the zoo, even though it’s been a regular stop for a while. Unfortunately the zoo visit is the weakest section of the film. The couple notes that the animals have food and security, but that’s such an obvious point that it doesn’t provide much insight. What are people supposed to do, let zoo animals starve? It’s an observed irony that adds little to a film full of observations of real problems. To top it off, the sequence is dull. Much of it consists of inset shots with the voices of the couple commenting on the animals. The whole sequence is uninspired.

It only seems necessary to get the couple to a darker place. Yuzo suggests that they go back to his room, his roommate is out, and you can tell from Masako’s reaction that it’s for exactly the reason you’re probably thinking. And it casts a pall over their conversation as Masako tries to come up with a good excuse not to go. The darkening mood as things go wrong is reflected in the fact that it starts to lightly rain, the weather reflecting emotional mood is a swiftly developing trademark.

A flyer for a Schubert concert, the first concert they went to as a couple, gives them some hope to salvage the afternoon. It’s only 10 yen apiece and “art is for the masses”. It results in a race through Tokyo as they try to get to the concert. And it displays Kurosawa’s chops as an editor and action director. It’s a decidedly modern bit of editing and features Kurosawa’s trademark cuts on action. It’s a sequence that technically doesn’t need to be

in the film, Kurosawa could have easily just cut to the couple running up to the theater, but it breaks up the couples wanderings and talking into a scene of action and excitement adding variety and adrenaline to the movie. It’s a small sequence that indicates Kurosawa’s growing mastery of pacing and variety.

All seems to be back on track. They arrive in time and tickets are available. But racketeers arrive at the ticket booth a few feet before them and buy up all the tickets. And then start scalping them at 15 yen instead of 10 yen. Yes, Ticketmaster’s practices are exposed as villainous by Kurosawa. Even if he wasn’t proud and frustrated, Yuzo doesn’t have the money to pay for these tickets, and so a confrontation arises as Yuzo demands that he be sold tickets for 10 yen apiece. The confrontation soon escalates into a fight and Yuzo gets a beatdown from the racketeers. It’s a public humiliation to his already damaged manhood. To top it off, it starts to pour.

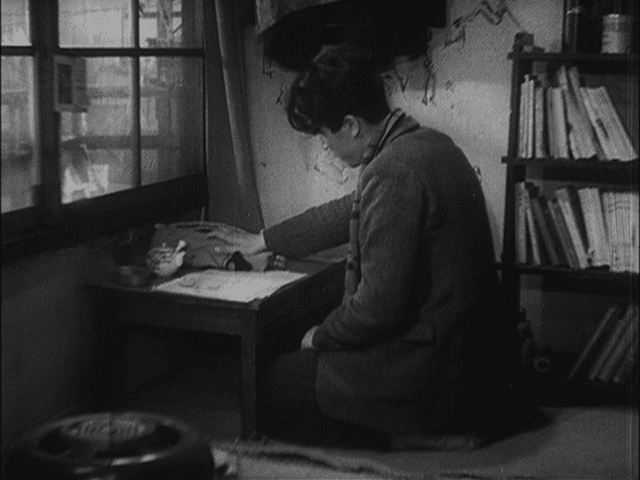

The couple retreat to Yuzo’s room. And while the rain beats down, Yuzo confronts Masako about his intentions. The guy’s been so emasculated throughout the day, it is little wonder he attempts to regain his manhood. The confrontation seems like the last straw as Masako leaves in tears and Yuko is left alone to stew. This is one of the key scenes for Isao Numazaki and Chieko Nakakita to show their acting chops and they’re both fairly good, albeit not up to the standards of Susumu Fujita or Setsuko Hara. One of the things Kurosawa handles about their confrontation is although it’s hurtful it’s handled in such a way that one’s not a monster and the other a victim. They’re two people under stress and making mistakes born out of a deep hurt.

Yuzo is clearly in the wrong though. And Kurosawa makes him pay in a scene that’s among his best ever. Yuzo is left alone, the rain pounds outside, a song plays in the apartment complex, and Yuzo is left to stew in his own misery. Kurosawa plays this without a word of dialogue as we observe Yuzo in an extended sequence. It’s a thoroughly modern moment that could play in a movie today and it’s powerful. Even if Kurosawa was no longer a new director, the confidence in his ability to let images and sound tell a story is something a lot of experienced directors never show. And Yuzo is given a reprieve as Masako returns and he sees how far he’s pushed her away and his unintended cruelty. He begs her forgiveness and they reconcile.

The reconciliation signals a shift in the film. The film drops its concerns about corruption and the style shifts from neo-realism as the couple now ventures outside into a Tokyo that’s clearly composed of studio sets. The tone of the film shifts where it was once hardnosed neo-realism, it’s now something akin to Frank Capra. They go to a little café to celebrate their renewal as a couple and discover that they don’t have enough money to cover the bill. Instead of a show of machismo, Yuzo dutifully hands over his coat as a deposit with the promise that he’ll be back tomorrow to reclaim it. Perhaps it’s Kurosawa’s suggestion on how best to deal with the demands of the shattered economy, with as much honor as one can muster.

Outside the café, the couple discusses their own dreams. To open a café that charges fair prices and good customer service. The non-reality of the sets softens the idea of a rebuilding Tokyo and gives it a romantic glow. The couple even play act what it would be like in this fantasy substitute for the real Tokyo. The spell lasts until they’re observed. Their dreams are for them alone. It’s very evocative of Capra and with his long messy hair and constant games with his hat, it’s possible that Kurosawa viewed Yuzo as a stand-in for the type of characters Jimmy Stewart would play.

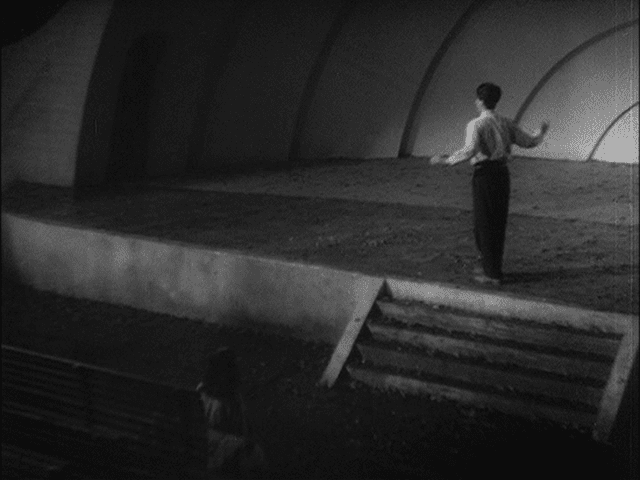

Finally they wander to an abandoned band shell, another victim of the war. Yuzo comes up with the idea that he’ll conduct an imaginary concert of the Schubert symphony. Even racketeers can’t steal their imaginations. But, even after strutting out like a proud conductor, he can’t quite muster the courage to proceed. In an uncharacteristic move from Kurosawa, Masako breaks the fourth wall and encourages the audience to applaud to encourage young lovers everywhere like Peter Pan encouraging the audience to applaud to revive Tinker Bell. Frankly, it’s one of the biggest missteps of Kurosawa’s career and would sink many a lesser movie. It doesn’t work on home video and it reportedly didn’t work in post-war Tokyo either. It stops the movie dead in its tracks.

Fortunately, Kurosawa redeems the misstep with another great sequence. Yuzo starts conducting, wind moves leaves around the band shell like dancers, Schubert’s music soars on the soundtrack, and the camera cranes and swoops with the music. Images and music work together to uplift and affirm the power of imagination to overcome reality. Not only do we hear the music, Yuzo and Masako hear the music. There is hope after all.

The couple has made it through the day and is renewed. Times are tough, but they have their honor, their hopes and dreams, their imagination, and each other. The movie ends on a happy note and a promise that things will get better.

One Wonderful Sunday, perhaps due to its episodic structure, has some extremes. The apartment sequence and the imaginary symphony are two of Kurosawa’s best sequences of any period. However, the episodic nature leads to sequences that don’t really contribute much, the switch in tone from neo-realism to a Capra-esque movie world is sudden, and the fourth wall breaking doesn’t work at all. There’s so much that’s good, observant, and exciting film making that One Wonderful Sunday still holds up as a good movie with a powerful message of hope, just a film slightly overstuffed. Kurosawa, in retrospect, regarded the film similarily. He’s quoted saying “I had a lot of things to say and I got them all mixed up…”. Still, it was reportedly popular and Kurosawa won a Best Director prize for it.

Perhaps Kurosawa wasn’t totally happy with the final result without the benefit of hindsight, because his next movie covers the difficulties in post-war Japan again. Only in the interim, Kurosawa will discover Toshiro Mifune and a legendary partnership is born.

Next Month: DRUNKEN ANGEL (1948)