Writing about Rashomon at this late stage is a challenge to a reviewer. What possibly can be added to the conversation? The orthodox view is that it’s one of the greatest movies ever made. One can even proclaim it as the greatest movie ever without it being considered a particularly controversial opinion. So much has been written about Rashomon that it’s hardly necessary to add to the conversation. Yet, Rashomon is all about the subjectivity of perception, so it invites an individual response like few other movies.

Given its historical reception, it’s perhaps surprising to learn that it was a struggle for as accomplished a director as Kurosawa to get Rashomon made in the first place. Rashomon was based on a pair of short stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, “Rashomon” and “In a Grove”. “Rashomon” basically gives the frame of the film, a ruined station where travelers relate how harsh the world is, while “In a Grove” tells the story that makes up the center of the film, a bandit, a samurai, the samurai’s wife, rape, and murder, only with seven different witnesses to the tale. “In a Grove” basically concludes that there is no single truth, although Kurosawa obviously had a different opinion. But, Kurosawa’s conception of the film was tough for the studio heads to comprehend. There was no movie precisely like Rashomon before Kurosawa made it. Even Citizen Kane, with its mixed film stock and telling the story from several different points of view is more a puzzle movie, fitting since jigsaw puzzles are featured in the film, than a statement on subjectivity. We’ve lost that sense of revolution since Rashomon has become so fixed in cinema, but every studio rightly viewed it as a risk that would leave audiences bewildered. It took Kurosawa several years to get the film made, through his own perseverance and belief in the project.

What’s more it was a break for Kurosawa from what he had been doing. Kurosawa had abandoned the historical film for about half a decade in favor of the contemporary neo-realist film. Turning away from contemporary concerns signals a change in Kurosawa the director, a director now most interested in “big picture” ideas. Kurosawa would return to contemporary concerns and stories, but the rest of his career springboards from Rashomon to a remarkable extent.

But enough rambling, it’s time to get on to the film.

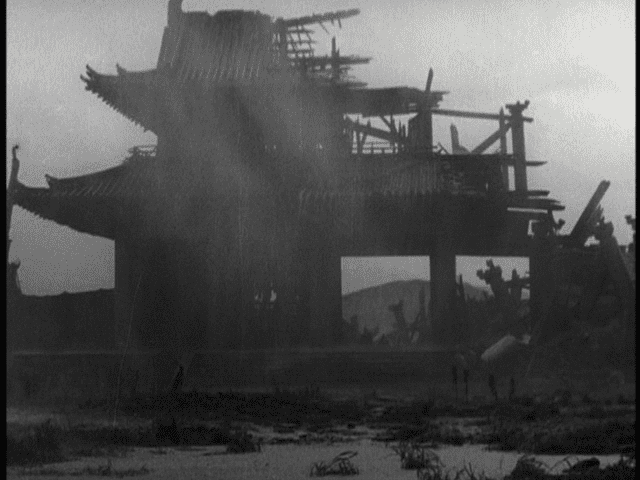

Kurosawa opens on the impressive ruins of a Japanese traveler’s station, Rashomon station, amidst a truly epic downpour. It’s not an exaggeration to claim that the heavens’ weep as the question of whether there’s any truth in the world is pondered. Usually, Kurosawa’s weather tends to merely comment on the action, but in this case the weather affects the plot. It forces three characters, a woodcutter (Takashi Shimura), a priest (Minoru Chiaki), and a commoner (Kichijiro Ueda) together as they await the passing of the storm.

Kurosawa reveals the woodcutter and priest through a series of axial cuts, putting his mark on the film. Even before the commoner shows up, we can see that something is bothering the pair. It doesn’t take the commoner long to figure that out either. Given that they’re all trapped by the storm, a story to ponder and pass the time sets up the flashbacks that drive the film.

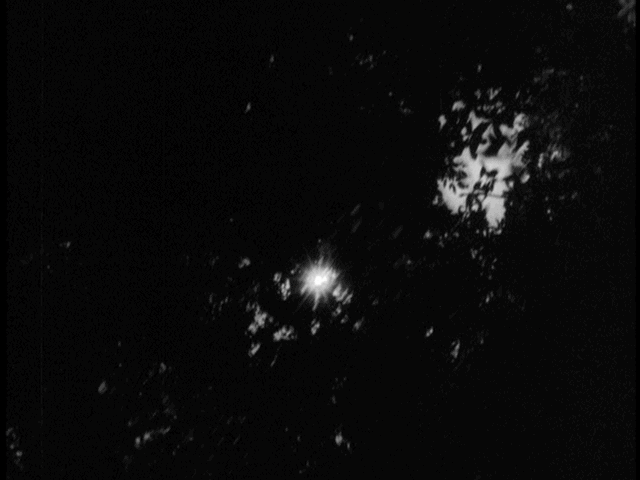

It doesn’t take much cajoling and the woodcutter relates his story of finding the body of a samurai (Masayuki Mori) and the subsequent trial. It opens with one of the most famous sequences of Kurosawa’s career as the film follows the woodcutter’s trek into the woods. There are cuts on action, tracking shots, and shots of the sun through the leaves of the trees. It’s been mistakenly referred to as the first time that a movie camera was pointed at the sun, Kurosawa himself did it earlier with Stray Dog, but it’s certainly the first widely seen movie to do so.

The sun shining through the leaves is important, Kurosawa isn’t creating a noir styled world in the woods, but a dappled world with light and shadow existing simultaneously and not being extreme in either sense. It’s a world not of stark blacks and whites and it comments on the story being told. Visually the film is a masterpiece, not just in the selection of shots but in keeping every shot consistent with the story being told.

Then, of course, the body of the samurai is discovered and the film shifts from the grove to the trial.

Kurosawa attempted breaking the fourth wall, unsuccessfully, in One Wonderful Sunday. He doesn’t quite break the fourth wall in the trial sequences in Rashomon, but he certainly pushes up against the wall as the characters testify directly to the camera. We, the audience, are to judge the testimony. While we can’t rely on much beyond the framing sequence, the simple trick of putting the audience as the judge of the action tells us that this section is to be regarded as reliable. The judge is never heard, even though he could have done so off camera, further heightening the illusion. Recently, A Separation used a similar setup for its story, another film where the audience is asked to judge right and wrong, truth and fiction, and the device is still effective to this day.

This is followed by the testimony of the priest, just confirming some facts as to the whereabouts of the samurai and his wife (Machiko Kyu). Finally, we have a policeman (Daisuke Kato) bring out the bandit Tajomaru (Toshiro Mifune) and we start to get to what exactly happened in the grove of trees.

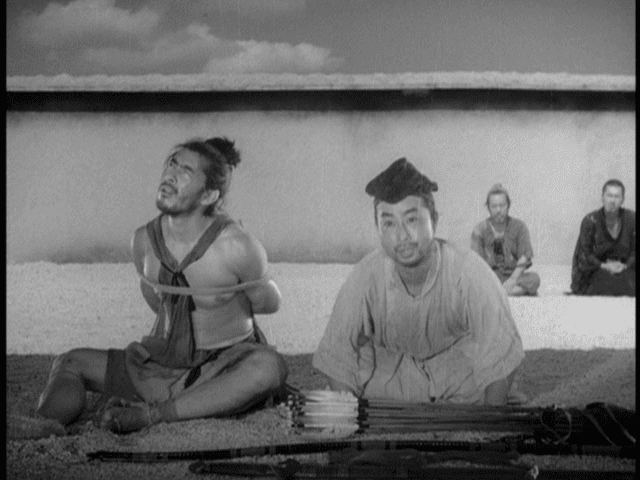

Before we dive into that, it’s worth noting that Rashomon features big ideas on what must have been a fairly modest budget. The court of law is basically a gravel courtyard with a wall in the background. There’s some on location filming in the woods. The one major set, the ruined Rashomon station seems to be the only major expenditure on Kurosawa’s part. Couple it with the fact that there are only eight speaking parts in Rashomon (half present in the above picture) and it’s an example of getting the most for your budget.

Getting back to the story, the scruffy, fleshy Toshiro Mifune is the image I have of the great actor and this is the first appearance of Mifune in that form. I like the more urban image of Mifune from Kurosawa’s earlier films, but getting a raw, unrestrained costume to go with Mifune’s often unrestrained characters really makes an impression. Unfortunately, Mifune goes too big in this role. The character is meant to be a braggart so it’s not a real flaw in the film, but Mifune could have dialed it down without losing the essence of the character. He’s a big character, but not bigger than life even if Tajomaru frames his story on a grand scale.

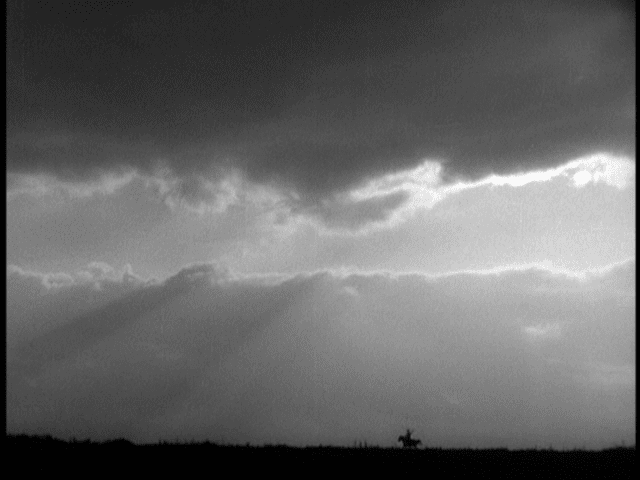

One of the things that notable about Rashomon is that even though it’s making a statement about one idea, the subjectivity of truth, it knows when to ponder other ideas. The notion of luck plays a role in Rashomon. Things may have turned out differently if the wind had not picked the right opportunity to unveil Machiko Kyu’s face to Tajomaru. Or if Tajomaru had stumbled in battle at the wrong time. These ideas aren’t just in the script, but are evident in how Kurosawa frames the images and directs the action.

A chance glimpse, and Tajomaru’s course of action is fixed. And, predictably, ends in tragedy. The samurai husband gives into his greed at the promise of treasure and his overconfidence that he can take out the scruffy Tajomaru. Tajomaru has to humiliate the samurai further by bringing the wife so that the husband can view her rape. And the wife has to deal with her victimization and the husband’s pride. Much of this is constant across stories.

Kurosawa does well to treat each of the stories equally. He doesn’t particularly change up styles or emphasize characters more than their place in the story calls for. He moves among the three characters in each story. Often Kurosawa uses his depth of field to make sure that we can see multiple characters in the same shot. Kurosawa uses his shots to illustrate a triangle of characters at every opportunity.

The fallout of the rape is where the differences in stories crop up as we see the characters react to their circumstances. Tajomaru’s story is perhaps the most straightforward. He see’s himself as a great thief and his story reinforces that. Right down to an epic sword duel.

It’s worth considering that this is Kurosawa’s first sword fight. And it’s everything a sword fight of this nature should be. It’s exciting. It has shifts in momentum. And it ends as much as by chance as by skill. We know the outcome already but how it plays out is exciting to watch regardless as we don’t know when or how it will end.

On its own, the film to this point would be a terrific textbook on how to make a film. It’s expressive. It’s exciting. It’s dramatic. And then, Rashomon truly gets great as it moves into its other stories.

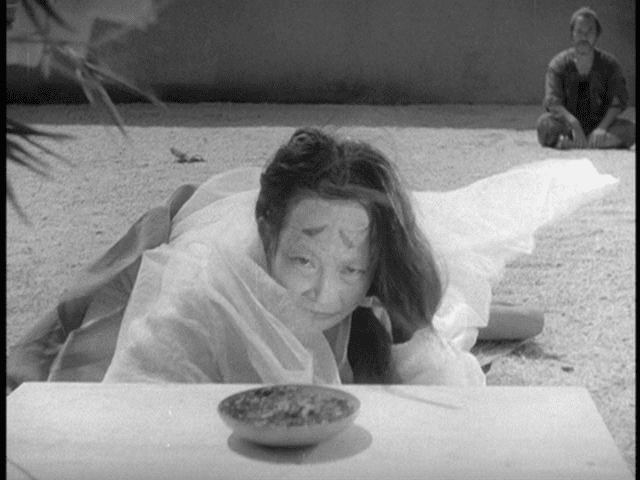

First up is the wife’s story. If there’s a standout actor in the film, I’d argue for Machiko Kyu. She is put upon and has to demonstrate the most range from victim to instigator. She has to move from fear, to shame, to anger. He face is expressive and clear always as she struggles with the situation. More than any other character she gets to react and that’s always a great showcase for acting.

The story ends inconclusively with the wife convinced that she must have killed her husband, not Tajomaru.

Perhaps if there were only two conflicting stories you could dismiss one. She’s ashamed. Tajomaru is a braggart. Kurosawa tosses in a third as we get the husband’s side courtesy of a medium.

It’s a shame that Kurosawa never really directed a horror movie, because his handling of the medium, her movements, and the voice that comes out of her mouth is impressively unsettling.

The husband’s story paints the wife as someone who victimizes him again. She becomes a harpy that wishes him dead and is easily led astray by the Tajomaru. But, he’s left alone to ponder his failures and opts for suicide as the only honorable way out. Rashomon is a film that lets its images speak even more than its words, perhaps reason for its international success, and this sequence is a particularly quiet one. Fitting, considering the ending.

At this point, it’s impossible to reconcile the stories. As a modern westerner, you can toss out the medium as being inherently unreliable and unbelievable, but as a filmgoer presented with this evidence it’s an exercise in logic that leads nowhere. This isn’t a trial, this is a film. The logic that applies to film isn’t the same logic that one brings to a trial. The filmmaking itself is evidence.

And, to his credit, Kurosawa both finds a way to unravel the threads and still preserve the idea that there’s inherent subjectivity in truth. Kurosawa could have simply cut to show us what really happened. Instead, Kurosawa finds another unreliable witness (aren’t they all?), the woodcutter, with his own agenda.

In the woodcutter’s story, the tables are turned and some of the hypocrisies of the samurai class are attacked head on such as the victim being blamed for the crime. And, the wife gets to goad and shame the men after her shame.

It’s worth noting that it must have been very hot when Kurosawa shot the grove scenes of Rashomon. There’s sweat on the faces of the characters throughout the films. Kurosawa doesn’t call attention to the heat, but he doesn’t have to. And it makes the final confrontation between Tajomaru and the samurai all the more visceral.

The final fight might even be viewed as a deconstruction of the final duel. It’s clumsy. The characters breathe heavily and are visibly frightened. It might be called more realistic, but that’s perhaps an overstatement. For a director that had never directed a sword fight before, Kurosawa directs two completely different types of movie sword fights and excels at both of them.

Kurosawa paints a pretty damning picture of humanity, even if you don’t believe the woodcutter’s story is rationalization for stealing the expensive dagger from the scene of the crime. Yet, while the film to this point may represent Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s stories and is a great representation of Kurosawa’s talents as a filmmaker, it doesn’t represent Kurosawa’s views on humanity. He’s still too much of an optimist.

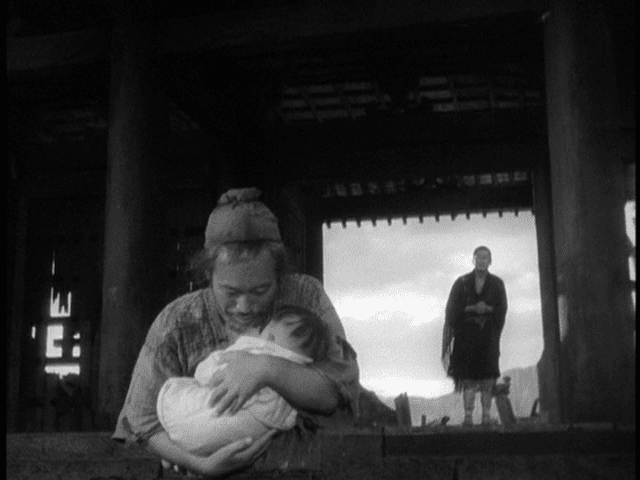

The coda to the film revolves around the woodcutter, the priest, and the commoner again. They’re considering the final revelations when they hear a baby cry within the ruins. The commoner finds an infant, abandoned by its mother, and steals the few meager belongings left that could provide for it. However the woodcutter, in a pure streak of humanity, takes the baby home with him. He’ll provide for the baby as best he can. The rains stop and the priest’s faith in humanity is restored by this gesture.

In this way, there are still truths in the world. No one can rationalize away the fact that stealing from a baby is evil. And that caring for an abandoned baby is an act of charity. Most of the world may exist in a dappled gray area, but that doesn’t mean that good and evil don’t exist. Kurosawa takes liberties with the source material, and makes a legitimate statement of his own which is perhaps truer than the source material.

What’s fundamentally great about Rashomon is that it illustrates a subtle example of human perception in clearly cinematic terms. It’s fiction illustrating truth. People filter the world around them in various ways and their perception colors the events. I’ll point to Series 3, Episode 2 of High and Low (Brow) as an example of this phenomenon in action. We’ve all had these moments in our lives, although seldom illustrated as effectively as Kurosawa’s film.

If there’s any ground for criticism of Rashomon it’s perhaps that Kurosawa exaggerates the differences in perception. The Rashomon effect is usually much more subtle, usually consisting of subtleties like inflection or interpretation of body language, not presenting itself as seemingly contradictory as the various episodes presented in the film. But, Kurosawa isn’t attempting subtlety here and the idea that subtle is always better isn’t necessarily true. We might not even be talking about Rashomon as a universally understood film today if it was more subtle. Trying to explain to a non-English speaker the dialect humor of something like Fargo is likely to be an effort in frustration. Kurosawa’s blunt illustration transcends language limitations and became a universal touchstone of cinema.

Rashomon did fine in its Japanese original release and undoubtedly made the studio money. It reportedly wasn’t much loved by the contemporary Japanese critics, although that may be exaggerated. The head of the studio claimed he didn’t understand it. Still, it was entered in the Venice Film Festival almost by accident as the Japanese film heads couldn’t come up with a film that they thought the west would enjoy and it was only at the urging of Guilliana Stramigioli, head of Italiafilm in Japan, that the film was entered. And it subsequently won the Golden Lion, then perhaps the most prestigious world film prize. Overnight, Kurosawa became a worldwide name.

Kurosawa, however, never anticipated that Rashomon would be the film that would make him famous. He was already at work on his next film when he won the prize and perhaps hadn’t fully grasped what he had tapped into. The post-Rashomon effect on his career would have to wait until he completed production on his next film. A film that had perhaps a more prestigious pedigree if less apt to be free from studio meddling.

Next Time: THE IDIOT (1951)