After the international successes of Rashomon and Ikiru, Kurosawa had an enormous amount of clout and turned to a historical epic for his next work. In a line that was characterized as arrogant, Kurosawa said “jidai-geki (the samurai genre) faces a dead-end, there are no talented jidai-geki producers”. Well, it’s not arrogance if you can back it up and after spending an unprecedented year in production, it was the most expensive movie ever made in Japan at the time, Seven Samurai emerged to the world in 1954 and its reputation today is as one of the greatest movies ever made.

I’ll make no bones about it, Seven Samurai is my favorite film. I think it’s a flat out masterpiece. But, it’s a challenge to write about a film that’s been as endlessly dissected, referenced, and discussed as Seven Samurai. How can you try to encompass the whole film in a piece that will take considerably less time to read than the movie runs for a movie as full of technical achievement and meaning as this one? Is there anything new to really say?

The best place to begin is simply at the beginning. Seven Samurai has a very straightforward plot. After a brief bit of text explaining the setting in Japan’s civil wars while bandits roam the countryside, we cut to a series of bandits on horseback galloping through the country. They stop at a point overlooking a village which introduces one of the defining characteristics of the film, deep focus photography. The bandits loom over the village with both clearly in focus. At least most of the village, the graveyard is not in sight, but it will be before the end of the movie.

The bandits debate sacking the village now, but one of their own objects saying that they sacked the village last fall and there will be nothing of worth. They agree to come back when the barley is ripe, when there will be something worth stealing.

They ride off and it’s revealed that a villager has overheard the bandits’ plan. He hurries off to the village. Kurosawa keeps his god’s eye view of the village as we can see the villagers huddled together in despair. With a series of axial cuts and close-ups he moves the story into the village and inserts the p.o.v. within the village itself. There’s much talk about humbly appeasing the bandits, before Rikichi (Yoshio Tsuchiya) proclaims that they should kill all the bandits. An idea that is immediately scoffed at, but which gains some traction.

The villagers go to the village elder for advice and he tells them a story about a village that he saw survive a series of attacks because they hired samurai. The villagers are intrigued but know that they can’t afford to hire samurai. And what kind of samurai would take money, much less food and board, anyways? The elder’s response “Find hungry samurai” is to the point and sets the story and major themes in motion.

This is evidently not a typical village. Whether through pride or desperation they’ve been driven to act against type. And they’re seeking samurai that have fallen low, ronin, and perhaps aren’t too prideful to serve. Class is one of the underlying themes of the film and one of the reversals the film promises is that samurai are now going to serve to protect, rather than oppress, the peasants. At least, that’s the theory, but what are the samurai getting out of it? And what kind of samurai can they attract?

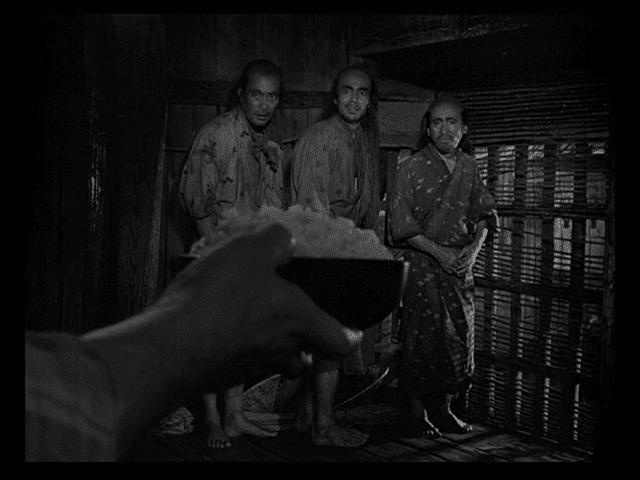

Those questions are quickly addressed as the film shifts scenes, via wipe cut, from the village to a nearby city where Rikichi, the comical Yohei (Bokuzen Hidori), and the sour Manzo (Kamatari Fujiwara), try to recruit samurai. And find that the reality of doing that doesn’t match the easiness of the theory.

There are plenty of samurai that still have pride and will have nothing to do with the lower class. The farmers find themselves being the butt of jokes by a group of lowlifes and finding only hostility or outright incompetence to their entreaties. The whole adventure looks like it’s over before it begins.

And then Takashi Shimura enters the movie and everything changes. There’s a commotion in town. A child is being held hostage by a bandit who was discovered during a burglary. And a samurai, Kambei Shimada(Shimura), is seen cutting off his top-knot and having his head shaved like a priest. There’s no reward, it’s simply a good deed, and this samurai is obviously not too proud.

Into the gathering crowd, two notable spectators gather. The first is a young samurai Katsushiro (Isao Kimura). Kimura had made his debut in Stray Dog as the object of Toshiro Mifune’s quest and Kurosawa had used him in a bit part in Ikiru, and this is a big role for him. The second, center stage carrying an enormous sword, as if he was compensating for something, is Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune). Like everyone else they’re curious about what Kambei is up to and with a deft bit of unrelated action to the main plot, Kurosawa is able to bring together a good chunk of the principal cast.

With the offer of a pair of rice balls, Kambei the monk gets the thief to let his guard down. We don’t see what happens, but Kambei rushes in and moments later the thief stumbles out, to die in slow motion as the wind blows dust around him. This might be the very first slow motion death on film and it’s a staggering one.

With that, Kurosawa has established the cunning of Kambei and his competence in a high pressure circumstance. It’s an action unrelated to the main plot, but it feeds back into it. The unrelated bit of action establishing the main character is a hallmark of much of action film making to this day. And the fallout from the scene immediately feeds into the plot.

Kikuchiyo, in a wordless scene, wants to measure himself against Kambei and Kambei has no use for the posturing. Katsushiro wants Kambei to teach him to be a great samurai, and although Kambei is flattered he doesn’t regard himself as great. He’s old and has always been on the losing side. And finally the farmers petition Kambei for help.

Kambei is initially flattered and somewhat excited by the challenge but he all but says “I’m getting too old for this shit” although he gives the farmers his sympathy. Kambei’s expression of sympathy is immediately mocked by the lowlifes who have been providing a running commentary. They point out that the farmers eat millet while offering rice, all that they have. Kambei finally sees the truth of their desperation and agrees.

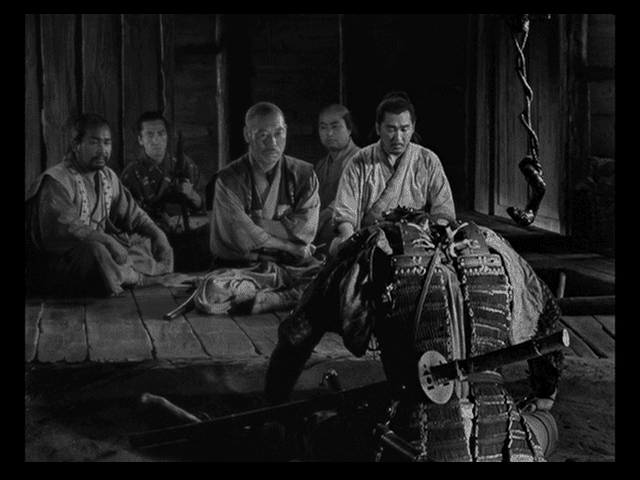

What follows is a swift series of scenes of Kambei recruiting: sometimes serious, sometimes comic. The recruiting serves as part of Kambei’s training of Katsushiro simultaneously tests the competence of the perspective recruits, and consists of Katsushiro trying to ambush samurai from behind the door. Again, Kurosawa is using deep focus for his advantage.

With the natural leader of men Kambei in charge, the ranks swell. Gorobei Katayama (Yoshio Inaba), a samurai who’s amused by Kambei’s test, is the first. With it, we see one of the first uses of Kambei’s most endearing traits, the rubbing of his newly shaved head. It’s a trait that George Lucas gave to Yoda out of tribute. Katsushiro ingratiates himself with the farmers, despite Kambei’s reluctance to include him, by paying for rice when they run out. Katsushiro is clearly not a ronin, but a samurai of means, putting him in a class above Kambei and the rest. Gorobei finds the good natured, natural comedian Heihachi Hasada(Minoru Chiaki) chopping wood. A man, who when introduced, will describe himself from the “wood chop” school of sword fighting. And Kambei runs into an old friend, Shichiroji (Daisuke Kato), a man who experienced defeat with Kambei but will follow him without question.

Most significantly, Kambei and Katsushiro witness a duel between Kyuzo (Seiji Miyaguchi) and another samurai in one of the standout sequences of the film. The contrast between the calm demeanor of Kyuzo and the nervous bluster of the other samurai makes it clear who the master swordsman is before they ever face off. And the face off is memorable with Kurosawa again using slow motion to remind the audience of the reality of death.

Katsushiro is instantly awestruck and with good reason. Kurosawa handles the duel beautifully as well as the transition from full speed to slow motion. It might be the earliest example of the concept of speed ramping which feeds into modern action film making. Kyuzo is a reluctant recruit, but he ultimately joins as he has no worthy opponent to test his blade against or cause to fight for.

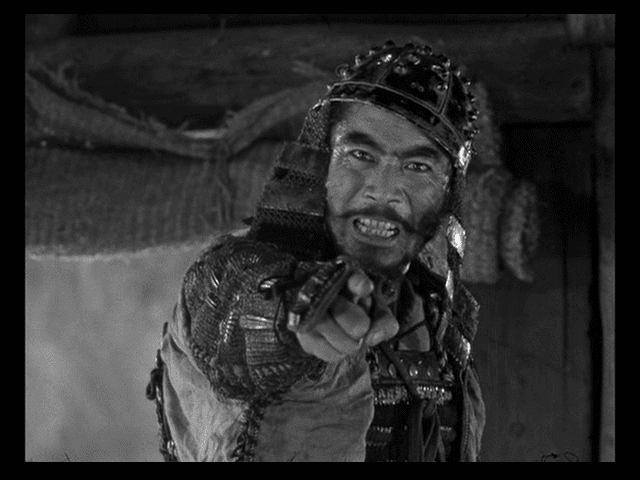

Ultimately that leaves them with five and time running out. A little arm twisting by the farmers gets Katsushiro included in the group making it six. And with the sense of a grand adventure running high, the local ruffians get involved and find a recruit. You get a sense that the ruffians are partly a representative of the audience getting swept up in this movie. Of course, the “samurai” the ruffians round up is Kikuchiyo, who’s drunk and fails the doorway test. He fails to prove he’s a samurai in more ways than one by presenting his pedigree, a pedigree that reveals him to be a teen. Kikuchiyo is no true samurai, although he desperately wants to be.

But Kikuchiyo is not one to take no for an answer and follows them to the village, demonstrating his skills along the way. He definitely has something to prove.

And once they get to the village, Kikuchiyo proves invaluable. Manzo, concerned about samurais seducing his daughter Shino (Keiko Tsushima), forcibly has cut off her hair in an effort to disguise her as a boy, which has set off a widespread distrust and fear since Manzo was one of the recruiters. If Manzo can’t trust the samurai to behave honorably, why should the rest of the villagers? Kambei and the elder of the village are stumped for a solution to this foolishness. Not Kikuchiyo who falsely sounds the alarm of bandits sending everyone running, including the samurai in a brilliant bit of cutting on action from Kurosawa, to the square to get organized. It’s evident that when it comes down to it, the villagers prefer samurai to bandits. It’s also evident that Kikuchiyo has more insight into the thought process of the farmers than the rest of the samurai, which makes him an invaluable addition to the group even if he is a loose cannon.

One of the best things about Seven Samurai is the way that Kurosawa sets up little crises along the way and pays them off. While the samurai set up their defense plans, helpfully laid out with a tour of the village complete with a map although the cemetery is conspicuously absent in the tour, you can see the seeds of ideas planted. This isn’t just a movie about a confrontation between samurai and bandits, but a film about class and community. And the individual motives of the various characters. Heihachi tries to solve the mystery of Rikichi, the man most eager to kill the bandits, by befriending him. Kikuchiyo shows nothing but disdain for the comically rustic peasant Yohei. Katsushiro and Shino meet comically and accidentally with the expected romantic results and the difficulties in keeping it a secret in a small village. The romance is given added juice with the unexpected idea that Shino is the more aggressive one in the relationship. The elder shows his pride, another common theme of the film, by being taken aback by the thought of abandoning his mill home on the other side of the river that’s impossible to protect. Kikuchiyo engages in comic hijinks involving a horse and finding a woman in the village. Even without the bandits, there’s no shortage of story.

As much as Kambei is the leader, the film really pivots around Kikuchiyo. He’s the link between the samurai and farmer. The samurai know he’s “passing” for one of them, but the full revelation comes near the mid-point of the movie when the samurai discover that the farmers have hunted defeated samurai in the past and have the spoils of their equipment. It’s shocking to the samurai to discover that the farmers aren’t the purely innocent victims they thought. Kikuchiyo, in a brilliant, angry scene by Mifune, further demolishes their illusions on what farmers actually are, and the fact that the samurai class has had a share of the blame in making them that way. Kikuchiyo shatters all the illusions, including those of the audience, that the samurai are pure heroes by speaking truth to their role in the status quo. Much of Seven Samurai is about class and this is undoubtedly the key scene that brings it to the forefront. The fallout is a mix of shame, for everyone involved, including Kikuchiyo who through the passion of his speech has revealed himself as the son of a farmer.

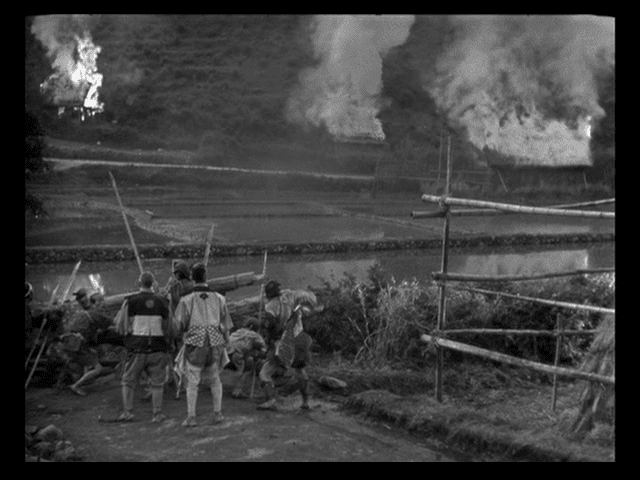

These simmering relationships play out in the background as the bandits ultimately attack in a series of thrilling sequences and all of Kurosawa’s trademarks are on display including masterful compositions, cutting on action, deep focus photography, some lovely nature footage, weather reflecting the emotional state of the characters, and a general command of the elements. Kurosawa is really at the pinnacle of his cinematic powers here and it shows. Much of the second half of the movie is about the siege of the village, and as an action movie alone it has few peers. What’s equally remarkable is how the characters aren’t lost in the action. We see Kambei’s calm leadership. We see Kyuzo’s skill. We see Katsushiro struggling to be a man. And, most of all, we see Kikuchiyo being reminded of his roots and flaws at every turn. Most particularly when he saves a child after the child’s family is slaughtered by the bandits and is reminded of how his family met a similar fate.

Kurosawa has set up so much in the first half, all that is necessarily is watching all of the subplots play out. We see Kikuchiyo’s pride get in the way, masking the shame of his ancestry and some of his actions, Katsushiro’s pains at trying to be a man, and the foibles of the villagers including Rikichi’s rage and the reason behind it. At this point, death becomes a part of the story. The bandits have muskets and a sword is no match for a musket, despite the skill of the swordsman. Shots ring out at maximum volume as we see the technological revolution spelling the ultimate doom of the samurai class.

It’s at this point that the village’s cemetery is introduced to the film and it will be a consistent presence all the way to the conclusion. Seven Samurai, for the most part, starts out as a fun lark, but as war breaks out and casualties mount it becomes grimmer and grimmer. It’s still a marvelous action film, but it has real stakes for the characters and its share of tragedy. All of which builds to a monumental final battle in a torrential rain storm. Words can’t do justice to the power of Kurosawa’s images, the rain, the mud, horses at a gallop in close proximity to people, real arrows getting shot into blocks of wood on stuntmen, and the emotional release of the participants. Seven Samurai was a long, difficult shoot on location, and the final results justify every bit of that difficulty. Watching Seven Samurai you appreciate the immediacy of the filmmaking, something CGI has yet to match.

It’s no secret that the village is saved from the bandits in the tradition of action-adventure films. On that level, it’s a complete success. But it also is a meditation on class and pride. In a crisis, the samurai and peasant can work together. But, when the crisis is past, the bonds of class are too strong. There’s no room for the samurai in the village in the aftermath. They have no place there, except in the cemetery. Seven musicians play a song as rice planting gets underway and the villagers celebrate, but the surviving samurai are left on the outside. They’re not part of the villager community and never can be. The only real room for the samurai is in the graveyard. The end is a mix of triumph and social tragedy and Kurosawa plays it for all it’s worth.

With Seven Samurai the “team action film” was formed and the cinematic world has been recycling the concept ever since. There have been direct remakes, The Magnificent Seven and Battle Beyond the Stars, and many movies that owe at least partial inspiration to Seven Samurai, everything from The Dirty Dozen to The Avengers. It’s one of the enduring templates of filmmaking. Seven Samurai is still a living, breathing part of modern cinema and not a museum piece representative of a bygone era.

Seven Samurai was an enormous success upon release, in Japan and abroad, and if it didn’t completely rewrite the historical samurai film, it at least set it at a high bar. After the long, difficult shoot of Seven Samurai, Kurosawa decided to tackle a smaller contemporary project based on the real fears of Japan in the nuclear age.

Next Time: I LIVE IN FEAR (1955)