In normal times, Kurosawa would have been given free rein after the success of Sanshiro Sugata. But it wasn’t normal times, it was World War II and Japan was losing. So Kurosawa was basically ordered to make a propaganda film with preapproved messages and material. The result was one of the most atypical films of his career.

Kurosawa, with his affection for western art and belief in individualism, was opposed to the regime in Japan and World War II. But it was a passive opposition and he was willing to put the goal of continuing to make films above his politics. At least to a point. Despite the propaganda office’s requirements, you can see Kurosawa’s beliefs sneak in at the edges. They don’t subvert the main message, but they support the idea that auteurism can never be completely hidden.

After the propaganda messages and the declaration that the film is “A MOVIE OF THE PEOPLE”, the film proper begins. The opening scene is a speech by the manager (Takashi Shimura) of an optics factory, which illustrates that Shimura was already assuming a place of authority in Kurosawa’s films. Shimura announces an emergency quota increase for the war effort; for men an increase of 100% and for women an increase of 50%. And, in a stroke that makes it a Kurosawa picture, he reminds the workers that they each must strive to become an outstanding individual as well. “One can’t improve productivity without improving one’s character.” And that theme of sacrificing and improving oneself becomes the central theme of the film. The film isn’t physical beauty, but the most beautiful in spirit. It’s also a smart script decision, because how interesting would a movie simply about meeting a production quota be?

One of the things that is immediately striking about The Most Beautiful is how much Kurosawa mutes his style in favor of a documentary look. The opening scenes of the speech, with the workers standing at attention and backlit look like Russian cinema of the period.

But the heart of the picture is when we get into the factory. Kurosawa was interested in a documentary style realism and shot the film in a real optics factory. (As you watch the film, you can learn many of the steps in the process of how optics are made.) He had his cast live in a dormitory, just like the workers of the story, march in a fife and drum corps, just like the workers of his film, and did everything to eliminate traces of theatricality. The camera moves are restrained. Most shots are at eye level giving a “you are there” feel to the picture. In its simplicity and emphasis on realism, it’s a precursor to the post-war neorealism movements in Italy, Japan, and elsewhere.

One of the ways that the film sticks out from Kurosawa’s filmography is in its use of women as the main characters. There are many fine performances by females in Kurosawa films, but they’re seldom the main characters. Here, they’re front and center and the film focuses on their trials and small triumphs as they work to meet the quota.

Right away, the film sets up the first crisis as the women respond to the speech in distracted groups in the factory. The quota increase being the source of their frustration. It turns out it’s not because the increase is too big, but that the women feel that they aren’t being asked to do enough. Although, this being pre-feminist times, they only ask for a 67% increase. It’s a small triumph for the women doing their part, and after that episode we’re introduced to the women as characters.

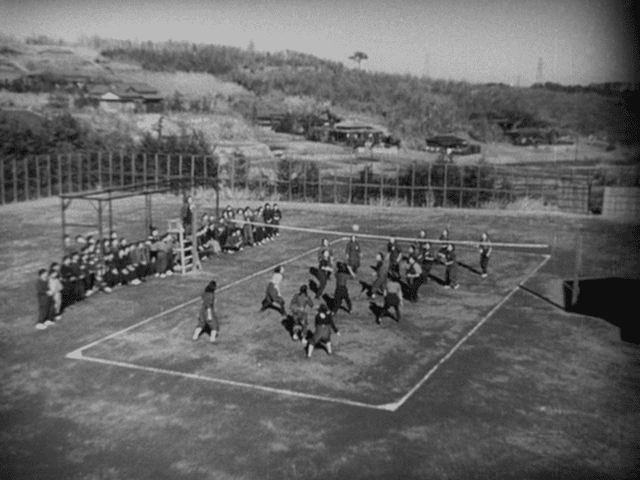

The principal character is Watanabe (Yoko Yaguchi ) who is the de facto leader of the women. The film follows an episodic structure for the remainder as we see the mini-crises which the group faces as they try to meet the demanding quota. (The quota goal being helpfully illustrated with an interspersed chart at various intervals.) Among the episodes that Watanabe must deal with is the production plummeting following a too quick start. Volleyball games organized to boost spirits. One worker becomes sick and is forced to go home in a tearful farewell. Another breaks her leg. A third is hiding her own sickness, with Watanabe as an accomplice in the deception. Watanabe has her own crisis with her mother falling ill. Interspersed with these personal crises are the volleyball games and scenes of their fife and drum corps marching in parades, respites for their individual trials in communal activity and purpose.

Much of the film is standard melodrama. What keeps it from sinking into sob sister territory is Kurosawa’s tight control on the tone. His emphasis on realism keeps the film emotional but not mawkish. At least for the most part, the weeping goodbye of Suzumura as she returns to her home sick is one of the few times Kurosawa indulges the more melodramatic side of his film. The restraint even works its way into the politics. The British and Americans are mentioned once, in a pledge of allegiance to destroy the enemy, but never again and they’re simply presented as “the enemy”. There’s no stereotyping that can mar even Allied propaganda films of the period to this day. It’s a story of a group of women doing their best in trying circumstances and for the most part it’s content to leave it at that.

Although the camera work and acting are very down to earth, it would be a mistake to dismiss the film as lacking in style and energy. Kurosawa isn’t indulging fancy camera work and acting, but he lets himself loose full bore in the editing suite. The editing on the film is very tight and sophisticated. There are wipes. There are axial cuts. And there are montages. The full force of the movie is unlikely to be conveyed in a series of still frames, because this is truly a moving picture where the juxtaposition of images matters.

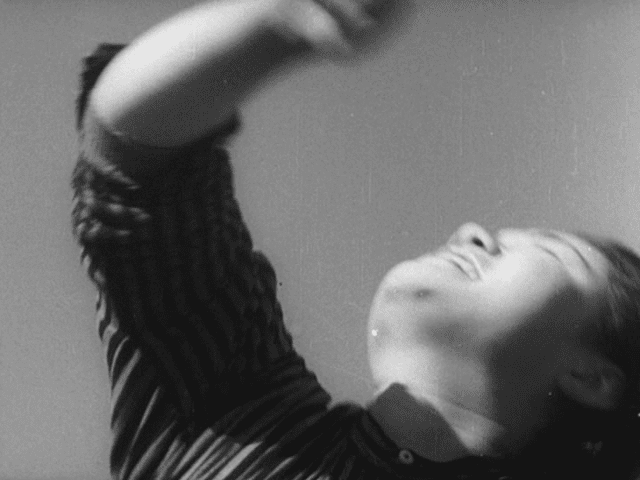

An example is the volleyball game mid-way through the picture. It’s a model of editing, beginning with far away shots giving an overview of the point, an axial cut to draw us closer, a cut to a mid-range shot at the net following the action, finally cutting to a montage of individuals, lovingly backlit, as they leap and volley, sometimes without the ball even being seen in frame. The montage is so effective that you can follow the implied action clearly and it puts you right in the action, almost as a participant. It is exciting filmmaking and an improvement over Sanshiro Sugata in many respects.

Events come to a head in the third act as we see what Watanabe is made of. The quota is in danger of not being met. The women under her charge accuse her of favoritism. Her mother is deathly ill. And, to top it all off, after being interrupted at work she’s misplaced a lens before finishing calibrating it. The reveal of the misplacement is an outstanding example of editing by Kurosawa rapidly fitting together scenes we’ve seen earlier where our attention was diverted elsewhere. After shaming her accusers with the revelation that her supposed “favoritism” was simply protecting a sick girl from being sent home, Watanabe sets herself the nearly impossible task of going through several days of lenses to check their calibration. In a skillfully edited sequence, it goes long into the night while she sings to herself to keep herself awake and fight the headaches the work is causing her. It’s an unnecessary, painstaking, lonely task, as the supervisors explain that there are other quality control checks along the way but it’s a point of honor for her and a triumph of character when she completes her task.

There are rewards that follow from that, as the group is fully reunited by the return of Suzumura. And it looks like the quota is going to be met. Into this triumph, Kurosawa throws the death of Watanabe’s mother. Watanabe won’t return for the funeral, following her mother’s wishes, but instead returns to her station, where tears stream down her face.

Triumph and tragedy are balanced. As Donald Richie notes in The Films of Akira Kurosawa, it will be a continuing theme of Kurosawa that “life is hard”. The rewards that Watanabe receives are internal, not external and the ending elevates it above simple propaganda into a work of art that can survive viewing nearly 70 years later as more than a curiosity.

Yoko Yaguchi is the heart and soul of the picture and turns in a really solid performance. Kurosawa was very demanding and the cast appointed Yaguchi as a go between. The director and his star butted heads often as a result, but in true Hollywood fashion, they became close and married in 1945. And they stayed married until her death in 1985. Kurosawa reportedly called the film one that was “most dear” to him, and it’s easy to read his subsequent marriage into part of the reasons.

The Most Beautiful certainly isn’t as fun as Sanshiro Sugata with its weepy melodrama and propaganda, but it demonstrates an increasing command of all the tools available to a director and indicates Kurosawa’s growing range. You definitely couldn’t dismiss him as a one trick pony after this film. And it foreshadowed post-war neorealism. In its own way, it’s nearly as successful as Kurosawa’s earlier picture, artistically and at the box office. Not bad for a picture that’s ostensibly about meeting a production quota.

That success would prove to be a mixed blessing in wartime. Kurosawa’s next picture would again be a propaganda film, but whereas he got to choose the story he wanted to tell for The Most Beautiful, he’d have it prescribed to him next time. And, to top it off, it was to be a sequel to his first hit, a film the censors had to be talked into releasing.

Next Month: SANSHIRO SUGATA PART 2 (1945)