Kurosawa had wanted to make a film based on Shuguro Yamamoto’s story “Peaceful Days” before he made Yojimbo. With the massive success of Yojimbo, the screenplay adaptation of “Peaceful Days” was reworked to be Sanjuro, the continuing adventures of Toshiro Mifune’s wandering ronin. Kurosawa, ultimately took over the job of directing the film, which he never intended during development of the script, while preproduction work was underway on High and Low. By all accounts the shoot was one of Kurosawa’s shortest and most fun.

What’s even better is that while Sanjuro isn’t likely to be called one of Kurosawa’s major works, it’s still an accomplished, highly entertaining film with a clear message. Not bad for essentially a lark in between major productions.

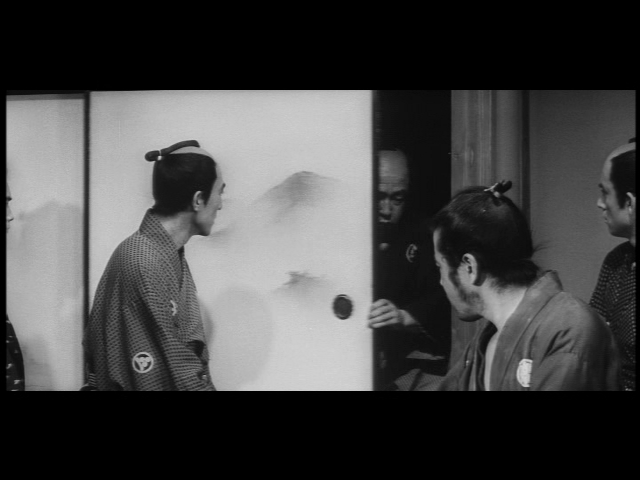

The film opens, somewhat surprisingly, without Sanjuro (Toshiro Mifune) wandering into town. Instead, we’re introduced to a gathering of young samurai in a temple. The lead samurai, Iiro Izaka (Yozo Kayama), breathlessly reports on how his goal of reporting corruption in the clan was apparently hushed up by his uncle Mutsuta (Yunosuke Ito), the Chamberlain of the clan. The uncle took their evidence and told them to go home and mind their own business, essentially. Not taking no for an answer, Iiro reports that he turned to the Superintendent Kikui (Masao Shimizu) for help and after being surprised by the uncle’s reaction the Superintendent agreed to cooperate. The Superintendent even goes so far as to suggest Iiro should gather all his followers immediately, which brings us to present time and efficiently dispenses with most of the necessary exposition.

Kurosawa frames the scene with Iiro in the center of the frame. He’s clearly the leader and the story is going to revolve around him. At least that’s the impression based on the setup. The other young samurai aren’t really given much characterization other than the hothead of the group. But, it’s clear that they’re all a bunch of idealists that believe wholeheartedly in making a difference and have a romantic view of the samurai life.

A foolish view, which is quickly pointed out as Sanjuro (Toshiro Mifune) intrudes on the scene. It turns out that he was sleeping in the back room of the temple and overheard their discussion.

With a few words, Sanjuro gets to the truth of the matter. He asks if the uncle is ugly and when told the response is yes, quickly surmises that the young samurai have been lured into a trap and the Superintendent is the corrupt force. Sanjuro is quick, but the Superintendent is wasting no time either and a glance out the window concludes that all escape routes have been blocked. Already the film establishes a “how are they going to get out of this one” sense of adventure. And it’s left to Sanjuro to take charge, which will define the remainder of the movie as he uses his head to get out of the tight spot.

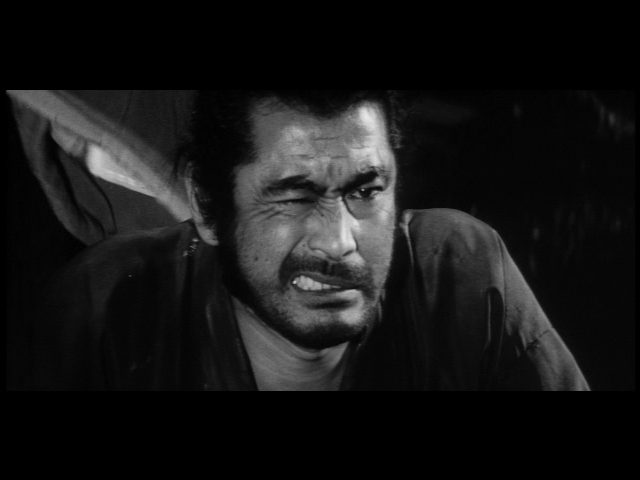

It doesn’t take long but the Superintendent’s men arrive and find a grumpy ronin, upset that his sleep has been disturbed, instead of a bunch of rebellious samurai. And the ronin wastes no time in letting his displeasure be known even as the most cursory of searches is performed. Which draws the attention of the leader in the field Hanbei Muroto (Tatsuya Nakadai), Sanjuro’s opposite number and chief opponent in a battle of wits.

Tatsuya Nakadai was Mifune’s chief nemesis in Yojimbo, and obviously Kurosawa wanted to repeat that success. It helps that Nakadai is playing a completely different character in looks and attitude. Moruto is no sadist, but a pragmatic leader in his own right who recognizes a kindred spirit in Sanjuro. Muroto’s first act, after sending his troops elsewhere, is to offer Sanjuro a job. It’s a connection that Sanjuro might take advantage of in a different time.

But, Sanjuro has already picked sides. In a bit of a repeat of Yojimbo, Sanjuro has hidden the young samurai under the floor boards of the temple. As they poke their heads out, it’s an image that George Lucas would re-appropriate for Star Wars and the smugglers compartments of the Millennium Falcon. They want to thank Sanjuro, but he doesn’t want their thanks, rather a few coins so that he can feed himself. Again it’s a contrast between the idealized world of these young samurai and Sanjuro’s pure pragmatism. Or almost pure, as Sanjuro decides to take some responsibility for these young fools who might get themselves killed out of their own idealism. Realizing that the Superintendent will act swiftly, they’re all immediately off to spirit the Chamberlain away.

Their adventure opens with immediate comedic results.

Ten samurai is clearly an unwieldy number. Sanjuro compares all of them creeping around to a centipede. Feel free to insert your own Human Centipede joke here, who knows, Sanjuro might actually have been an inspiration considering there’s a Japanese part in Tom Six’s film.

Again, the Superintendent and Hanbei Muroto are ahead of them as they arrive at the Chamberlain’s house in time to discover that the Superintendent’s troops are already there. Since they have no way of knowing where the Chamberlain is, Sanjuro takes charge sending many of the samurai off to spy on the houses of the Superintendent and his confederates while he plots the rescue of the Chamberlain’s wife (Takakao Irie) and Iiro’s love interest, Chidori (Reiko Dan). And, in a burst of action, Sanjuro kills two of the guards, while the remaining samurai capture one for questioning, and have spirited the women to the local barn.

It’s at this point that Sanjuro meets his moral opposite in the Chamberlain’s wife. Although she’s played for comedy, she’s just as naïve as the young samurai and totally unused to any physical exertion, she also embodies feudal nobility and ideals in a very real way. Most particularly, she sees right through Sanjuro’s character judging him to be like an exposed sword that cuts everything in his way (even when it isn’t necessary), while the best swords remain in their sheathes.

And, for once, Sanjuro has no response. Even against his better judgment, he lets the prisoner they captured live at her insistence. Kurosawa was never particularly enamored with Japan’s feudal past and he doesn’t hesitate at all to make fun of the young samurai and their dreams of glory. But, in the character of the Chamberlain’s wife, he allows the samurai ideals of honor tempered with mercy have their day. Sanjuro is generally a romp, and more often than not the Chamberlain’s wife is an object of humor, but unlike Yojimbo, there is a good side to this conflict and Kurosawa allows that side to express its ideals and even temper Sanjuro’s cynicism. The young samurai misjudge Sanjuro based on his appearance and mannerisms, and Kurosawa subverts the audience’s own judgment in the same way. We regard the Chamberlain’s wife as soft and foolish, while her judgments and pronouncements prove to be spot on and right, again and again. Kurosawa had used one version of the “wise fool” in Seven Samurai and here he presents another version.

To an extent, anyways. Kurosawa doesn’t let the ideas bog down the story, as there’s still an escape to be made with the two ladies, with Sanjuro offering himself as a footstool for the older lady. Kurosawa isn’t really known for his broad humor, but here he goes all in with Mifune playing the part to the hilt.

Continuing a playful mood, Kurosawa has the samurai hole up right next to the superintendent’s chief ally Kurofuji (Takashi Shimura), with the belief that the last place that their enemies will look is right under their own nose. In an irony, that’s the very same place that the superintendent is holding the chamberlain, with a wall, a little stream, and flowering camellia trees separating and connecting the two sides.

What follows are a series of feints and where Sanjuro starts to run out of fresh ideas. Hanbei Muroto is one step ahead of Sanjuro and the young samurai and they can’t even run a public relations campaign. Muroto sets up a trap which the young samurai are eager to rush into, but which Sanjuro keeps them out of. These events are necessary and fun, but they don’t really move the plot forward.

But, if the plot isn’t rushing forward, Kurosawa makes sure to stress that Sanjuro is very much an outsider. He is constantly depicted as separate from the group, dirty and constantly scratching, as contrasted to carefully coiffed and clean samurai. Even their prisoner, in a great bit of comic relief, almost becomes part of their group under the influence of the Chamberlain’s wife. His constant coming out of and retreating into the little closet the group has him “imprisoned” in is one of the great comic relief gags of Kurosawa’s career. Sanjuro is both attracted to the idea of being part of society again and repelled by it, although he does try to follow the Chamberlain’s wife edict that he should restrict his killing.

That conflict all comes boiling to the surface when Sanjuro announces to the group that he’s going to “accept” Hanbei Muroto’s job offer and spy on what the Superintendent is up to. Sanjuro’s plan, essentially a reprise of Yojimbo, spurs a fierce argument among the samurai. Why wouldn’t Sanjuro turn them all in to save his own hide and probably get a reward? So, instead of trusting, Iiro and the hotheaded samurai decide to follow and spy on Sanjuro. What can go wrong with that plan?

A lot can go wrong actually. Muroto welcomes Sanjuro with open arms. Muroto recognizes a man of Sanjuro’s skill and can relate to him on a level that the idealistic samurai cannot. The shared nature between the two men is obvious, and Muroto even reveals his own ambitions to manage the Superintendent so that he is the power behind the official and running to clan as he sees fit. And Muroto offers Sanjuro a place by his side.

Muroto is so trusting that he’s ready to reveal all to Sanjuro. Except for the fact that they both spot the young samurai spying on them. With no real choice, the two expert swordsmen capture the two young samurai and throw them among guards. Which forces Sanjuro to act, against his efforts not to kill people wantonly, to free the two samurai when Muroto leaves to get additional guards due to the importance of their two prisoners. Again it’s a reprise of Yojimbo, but a thrilling reprise nonetheless, as Sanjuro slaughters the guards in a tour de force action sequence.

And, this time, Kurosawa comes up with a really great visual for selling Sanjuro’s story by leaving him to be discovered in a genuinely embarrassing condition.

That embarrassment saves Sanjuro’s cover, but a failure that spectacular can’t be ignored as Sanjuro’s plan to infiltrate the Superintendent’s group comes to a premature and futile end which accomplished nothing but the unnecessary deaths of some guards. All that death is caused by a lack of trust.

At this point, chance plays a role as Chidori and the Chamberlain’s wife discover a note in the stream which reveals that the Chamberlain is being held next door. Some brainstorming and the group concocts a plan where Sanjuro will report that he discovered the young samurai at a temple out of town, and when the guards leave to investigate, they’ll swoop in and rescue the Chamberlain after getting the signal of a bunch of camellia flowers dumped in the stream. It seems like a perfect plan, except that the description of the temple is off which puts Sanjuro in jeopardy as soon as he steps through the gates.

The ruse is, of course, discovered after the guards leave, but trickery rules the day as Sanjuro convinces the Superintendent and Kurofuji to dump a bunch of camellia flowers of a certain color into the stream as the signal to call off the raid. The idea of flowers floating down a stream being a climax is a particularly Eastern and beautiful image which leads to a rousing, and surprisingly bloodless, ending of the Superintendent’s plot.

If Sanjuro was merely a fun romp, Kurosawa could have ended the movie right there, but even the lightest Kurosawa movies have some message attached. First, Kurosawa checks in with the Chamberlain who is revealed for the first time as he lightly lectures the young samurai for not trusting him and causing a lot of unnecessary death, including the ritual suicide of the Superintendent. The Chamberlain cuts them a little slack by telling a joke about his looks, but the lesson is communicated. A thanks was planned for Sanjuro as well, but he’s nowhere to be seen, which is something of a relief to the Chamberlain even as the young samurai rush out to find Sanjuro.

And it doesn’t take long for the samurai to find Sanjuro on the road out of town as he and Muroto prepare to square off in a duel. A duel that Sanjuro thinks is foolish and unnecessary, but which Muroto insists on since Sanjuro abused his trust.

The final duel sums up Kurosawa’s visual style and strategy succinctly. Much of it is a long take with a carefully composed composition as we wait for the two samurai to spring into action. The action is sudden, and violent with an impressive gush of blood as Muroto is dispatched, with a quick montage of reaction shots from all the spectators.

The duel brings no joy to Sanjuro who acknowledges that he cut down someone just like himself. Someone that could have been his friend and ally in different circumstances. Before departing for the road again, Sanjuro acknowledges that indeed the best swords remain sheathed and instructs the young samurai to remember that. An ironic end to a film that often that celebrates Sanjuro’s skill with the sword.

Which isn’t to say that Sanjuro is a tragedy. If it is, it’s the most enjoyable tragedy ever filmed. But, rather, it’s a film that acknowledges that there’s really no place in society for someone like our favorite ronin. Sanjuro may never get cut down out of foolish pride, but he’s clearly going to continue to wander in the wilderness.

It’s easy to imagine the continuing adventures of Toshiro Mifune in the role, but it would turn out to be the last pairing of Kurosawa and Mifune in a samurai adventure film. However, there’s no shame going out on a film as good and enjoyable as Sanjuro. Sanjuro may not be a masterpiece, but it’s only really because Yojimbo got there first. Audiences agreed as Sanjuro was yet another hit.

The pairing of Kurosawa and Mifune was still strong as Kurosawa was preparing his next film. Kurosawa almost always had a contemporary film lined up among his period films and he and Mifune would return to a crime thriller like their earliest outings. It would turn out to be another triumph, featuring one of Mifune’s best performances, and turn out to be one of Kurosawa’s most accessible films.

Next Time: HIGH AND LOW (1963)