After the commercial failure of Dodes’ka-den, his attempted suicide, and the difficulty of finding funding in a Japanese film industry that was going through major transitions, Kurosawa’s career looked over in the early 1970s. However, larger forces were at work; the Soviets were looking to improve relations with the Japanese in the spirit of détente and obtaining finance capital to exploit the resources of Siberia. That made a lot of things possible, including the Soviet’s Mosfilm financing a film and hiring Kurosawa to direct it, because even if Kurosawa wasn’t at the top of his game, he still was an international figure representing Japanese cinema. Kurosawa’s reputation really saved his career.

Kurosawa chose a memoir by Russian soldier Vladimir Arseniev as his subject matter and conceived of a great epic of exploration, friendship, and nature. It wasn’t to be an especially complicated film, perhaps indicating a lack of confidence by Kurosawa, but a film that Kurosawa knew he could make and which would undoubtedly find an audience in its splendid 70 mm visuals. Kurosawa set off to film it in the bleak landscapes of Siberia and the film shoot was reportedly grueling, it took 2 years and included filming in sub-zero weather. Kurosawa described the shoot as an “enormous military operation”.

The film is very straightforward. It opens in 1910 with Arseniev (Yuri Solomin) visiting a community that is carving itself out of the wilderness. The scale of the scene is impressive even if ’’ts simply a prologue. Trees are down all over the place with little consideration for their value except that they’re in the way of progress and civilization. Arseniev is looking for a grave, the grave of Dersu Uzala, which was under some fine trees but they’ve all been cut down. Arseniev probably finds the grave, which has certainly been impacted by encroaching civilization, and remembers his friend.

The film then cuts back to 1902 where Arseniev is leading a surveying expedition into the Siberian wilderness. The world is alien to much of the expedition and the success of the mission is very much in doubt in the wilderness.

One night, the expedition’s rest is disturbed by rustling in the brush. At first they think it may be a bear, but it quickly turns out to be a native hunter, Dersu Uzala (Maxim Munzuk). The confusion with a forest animal is a bit of an obvious statement by Kurosawa as Dersu turns out to be as much a creature of the forests as the animals he hunts. He’s amusing to most members of the expedition for his seeming simplicity, but he’s also comforting as a recognizable face in a foreign environment and he’s invited to stick around the expedition to act as a guide.

What follows is a series of episodes where Dersu shows his value to the expedition. Dersu finds tracks in the woods and accurately determines their date and the nature of the man who made the tracks, to the apparent disbelief of most of the expedition. A disbelief which turns to admiration when they later meet the maker of the tracks. Dersu accurately determines the location of a shelter that they can use to spend the night.

Dersu also demonstrates his kindness by demanding that the expedition leave food and matches for whoever may come along to the shelter after they use it, knowing that it could mean life or death. Dersu regards all living creatures as “men”, acknowledging his link with nature. Dersu even goes farther acknowledging water, wind, fire, the moon, and the sun as “men” which shape the very world that they reside on. All of this makes a positive impression on Arseniev.

Kurosawa shows Dersu to be an admirable individual that has a lot to teach, but he stops well short of making him into a clear mentor ala Takashi Shimura or superhuman ideal ala Toshiro Mifune. The relationship between Arseniev and Dersu remains on the level of good friends who learn things from each other and doesn’t rise to a mentor/student level. We learn much more about Dersu than Arseniev who seems to be a rather conventional sort.

The key scene to humanize Dersu is set after an impressive feat of shooting wins him a bottle of vodka in a bet. Dersu gets drunk away from the party and Arseniev goes to visit the man. There, Arseniev learns that Dersu wasn’t always the loner hunter, but rather a man with a family and a home. But Dersu’s family died of smallpox and his home was burned by neighbors in an effort to annihilate the disease in their midst. Since then Dersu has wandered outside civilization never setting down roots. It seems that Arseniev is the first real human bond that Dersu has felt in awhile and their bond is all the stronger because of Dersu’s years of loneliness.

It’s a bond that will be forged stronger by the events of the film.

The main event of the first half of the film is the journey to a frozen Siberian lake. Upon arriving, Arseniev and Dersu set out away from the camp to see the lake in a scene where the two men are dwarfed by nature.

The winds pick up and erases their tracks and the two men find themselves stranded in the wild without shelter as the surely fatal Siberian night closes in. It’s up to Dersu to devise a plan to construct a shelter out of the wild grass of the area. What follows is the strongest sequence of the film as they race against the setting sun, fighting the wind, the cold, and Arseniev’s exhaustion to construct the shelter. It’s likely that George Lucas took inspiration from this scene to create the cliffhanger of surviving the night on Hoth in The Empire Strikes Back. But, while the idea is a minor but memorable incident in The Empire Strikes Back, surviving the cold of a Siberian night is a major set piece of Dersu Uzala and Kurosawa plays it for all that its worth. The setting sun is constantly in the background as a reminder of how little time they have as it gets lower and lower in the horizon. And their survival is a triumph, almost entirely to the credit of Dersu who clearly saves Arseniev’s life.

Kurosawa skims over the rest of the expedition, with some impressive visuals showing the party struggling through the winter and the awesome landscapes that they’re traveling through.

Eventually they arrive at a native encampment with Dersu declining to come back to civilization with them. Dersu knows that he’d rather go chase sables than go to a place where he knows he won’t fit in. Dersu is a creature of the forest above all else. Eventually they depart with railroad tracks being the dividing point between civilization and forest.

The film then jumps ahead to 1907 with Arseniev leading another expedition into the wilderness of Siberia. Arseniev openly hopes to run into Dersu Uzala again and Kurosawa wastes little time getting the two of them back together for more adventures. Kurosawa visually shows their bond by showing the two of them separate from the rest of the expedition.

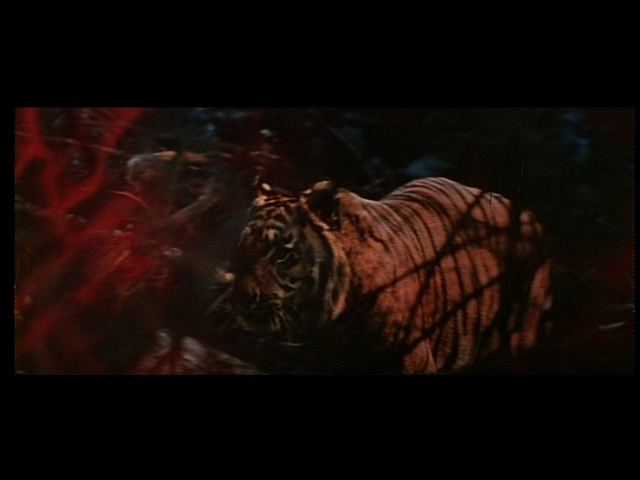

But, things are different this time. Dersu isn’t quite in his prime any more. A tiger crosses their path in the foggy forest stalking them without Dersu able to spot more than its tracks. The tiger will come to symbolize nature as Dersu’s nemesis.

There are other foes in the forest as the expedition comes across a series of pit traps left in place by a bad group of Chinese who have left them in place to trap animals and let them die of starvation instead of properly abandon them when they were finished. More Chinese bandits are encountered and Dersu and Arseniev’s men run them off and save some locals from a cruel death. If we see the good nature of man on the first expedition, the second expedition exposes the fact that bad men are encroaching on the wilderness.

And nature proves to be unforgiving again. A raft crossing of a swift flowing river goes bad. Dersu pushes Arseniev off, saving his life, and then finds his own life threatened as the raft floats swiftly downstream. A convenient branch caught in the river saves Dersu before the raft plunges over the rapids to its destruction. Much of the sequence is filmed in tracking shots giving a strong impression of speed and danger.

Fall goes well, and Kurosawa engages in some outright sentimentality displaying the friendship between Dersu and Arseniev in a series of vintage photos. But it’s perhaps the last ray of sunshine in the film for Dersu. As winter sets in, his eyesight goes with it. His aim goes with his eyesight and leaves him as a hunter with a declining ability to hunt. At this point, Dersu and Kurosawa ponder his mortality.

Age and mortality are catching up to Dersu and it’s something he’s not prepared for. The party comes across another tiger and Dersu shoots it in self defense. It’s an act that Dersu sees as an ill omen and likely to draw the ire of the forest spirits that are part of his religion.

Dersu’s crisis of faith and mortality reaches a pitch on New Year’s Eve when a tiger invades the camp. Perhaps its merely part of Dersu’s imagination, perhaps its real, or perhaps it’s the forest spirit of Dersu’s religion, but Dersu accepts Arseniev’s offer to join him in civilization once the expedition is over. For the first time, Dersu no longer considers himself at one with the forest.

The New Year’s Eve sequence is also Kurosawa’s one bid of indulgence in the bold experimentation in color that marked Dodes’ka-den. Kurosawa uses a red color overlay to indicate the spiritual presence of the tiger and the result is one of the most memorable sequences of the film. And probably the only really memorable one not involving majestic scenes of nature.

The film then shifts to Arseniev’s home city for the final stretch. Dersu bonds with Arseniev’s son (Dmitri Korshikov) and is looked upon favorably by Arseniev’s wife (Svetlana Danilchenko), but is unused to city life. This is the weakest section of the film as Kurosawa fails to dramatize Dersu’s struggles with city life other than a brief incident with a deliveryman. We see Dersu sitting glumly and we’re told about his issues, but this section is flat and static. It ultimately ends in a sitting room scene, using a classic Kurosawa composition, where Dersu finally makes the decision that he’ll go back to the forest as there’s no place in the city. Arseniev consents and gifts Dersu with a fine new rifle which he hopes will compensate for Dersu’s failing eyesight.

There’s no happy ending as Dersu never makes it back to the forest. Dersu is found dead and Arseniev is asked to identify the body. While men dig the grave in the forest ground under some majestic trees, the local police official concludes that Dersu was killed for the fine rifle he was carrying. Civilization has ultimately been Dersu’s downfall. Kurosawa ends the film with Arseniev placing Dersu’s ever present walking stick on his grave in a shot that strongly calls to mind the end of Seven Samurai.

Dersu Uzala is a rather conventional film in many aspects. It’s a bit sentimental and obvious in its themes and dominated by its impressive nature cinematography rather than human characters struggling with inner conflicts. It’s not experimental, but perhaps that reflects that filming in the midst of the Siberian winter, with an unfamiliar crew, in a non-native language is no place for experiments. It’s a lesser Kurosawa film, but lesser Kurosawa still has much to recommend and admire. There’s no mistaking that the cinematography is beautiful and Maxim Munzuk turns in a fine and affecting performance as Dersu. Yuri Solomin is rather good too, although he doesn’t get to display a lot of range in the film.

The film was a big success in Russia and did respectable business elsewhere. It was received well critically and won the 1975 award for Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars. At the very least, it convinced people that Kurosawa was still capable of making quality films, under difficult conditions, and that his career wasn’t over.

Still, it would take some time for Kurosawa to mount his next film, and it wasn’t his initial choice. Things were looking up though and George Lucas was going to remind everyone of Kurosawa’s legacy in a big way in 1977 with Star Wars. Even better, George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola would repay that legacy in making Kurosawa’s next film possible financially. It had been a tough decade for Kurosawa, but the final flowering phase of his career was about to begin.

Next Time: KAGEMUSHA (1980)