Undoubtedly sensing he was running out of time, Kurosawa rapidly turned around from Rhapsody in August to his next project. Madadayo would turn out to be his final film, and although he may have hoped to make more films, he fashioned a film that would serve as his goodbye if those hopes didn’t come to fruition.

Kurosawa loosely based the story on the life of educator and writer Hyakken Uchida, a professor of German linguistics for the Imperial Japanese Army Academy and later at Tokyo University. Hyakken Uchida was a beloved writer and a droll wit with a loyal following. At least, that’s the surface story; there’s certainly evidence in the film that Kurosawa also projected himself into the main character.

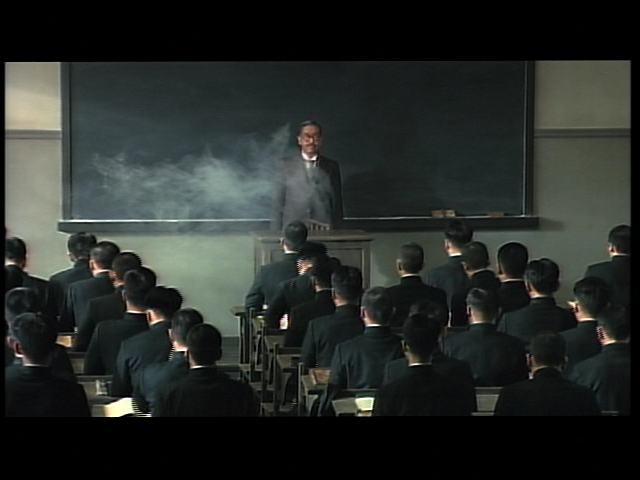

Kurosawa starts the film right at the incident that’s going to dictate the remainder of the story without buildup. The bell rings and a professor (Tatsuo Matsumura) enters the classroom of his German class. There’s cigarette smoke in the air and he chides the students and deeply inhales and jokes about how much he likes smoking. The smoke hangs in the air a long time, punctuating this sequence, which is a testament to how much in command of the environment Kurosawa always was.

The professor is clearly at ease and well liked, and Tatsuo Matsumura depicts warmth and wit, and then announces that he’s retiring as his books are selling. He’s decided that he can’t pursue two goals, even though he loves both, so this is his goodbye. The students are saddened by the loss of their beloved “sensei” and say so and stand out of respect for him. The professor chokes up with a quick, and effective fade to black cut from Kurosawa, which is a signal that the film is going to be episodic.

At this point, Kurosawa firmly establishes the setting as 1943, during the midst of World War II, and we’re introduced to the professor as he moves into his new home with his ever patient wife (Kyoko Kagawa) and the aid of his former students. Two students in particular are introduced, the pudgy Takayama (Hisashi Igawa) and the skinny, bespectacled Amaki (Joji Tokoro). Kyoko Kagawa was the established veteran of several Kurosawa films, appearing in The Lower Depths, The Bad Sleep Well, High and Low, and Red Beard, and is a welcome link to Kurosawa’s most productive period. Mark Cousins chose her to speak about Ozu and Kurosawa for his documentary The Story of Film: An Odyssey and she’s very good in her role. Takayama and Amaki are the main stand-ins for all of the professor’s former pupils.

During dinner after the move-in, we learn that the area has been frequenlyt burglarized in the past, and the professor thinkst he has a fool proof method to prevent them. That’s something that Takayama and Amaki are determined to test and to their relief and delight they find a series of signs that the professor has put up leading any would be burglar through the house, to a rest area with cigarettes placed out for the burglar, and an exit. Apparently the professor believes that a burglar will be so amused by his wit, courtesy, and hospitality that he wouldn’t dare steal from him.

Takayama decides to take one of the professor’s hats as a souvenir of their adventure, and Kurosawa evokes the image of Laurel and Hardy as they leave. This has nothing to do with the plot of the film, but simply is an exploration of the professor’s character and the affection of his former students for him. It’s a warm and funny anecdote.

The next chapter comes nearer to the main purpose of the film as the professor’s former students find themselves invited to his house to celebrate his 60th birthday. It’s the first of what will turn out to be the recurring motif of the film, the celebration of the professor’s birthdays with drink, songs, and jokes. It’s a largely raucous affair.

It’s also an occasion for the eccentric wit of the professor to shine. There are word plays and puns, which frankly don’t translate well and partly explains why Madadayo did not get a North American release. There are also stories that work very well, particularly the story that the professor had to supplement the celebration stew during war time with horse meat and was embarrassed at the butcher in meeting an old Army friend, a horse.

It’s all fun and games, although it’s the first time that Kurosawa really considered animals as having feelings and thoughts. His films were, by and large, more considerate of trees than animals. It won’t be the last time in the film that Kurosawa considers the relationship between animals and humans, which shows that Kurosawa was still finding new ground to explore.

The dinner discussion also covers fear of wartime blackouts, and the professor’s fear of the dark, which he considers quite right for a “proper human” with any imagination to have. This birthday is an occasion for celebration, as even in war, there’s much to enjoy about life.

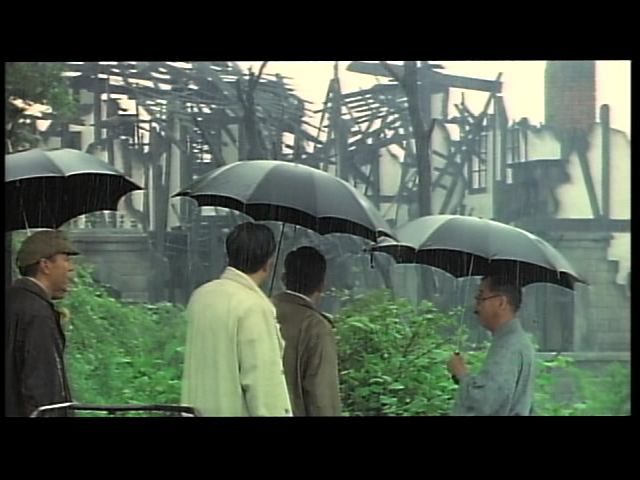

These light spirits are short-lived in the film, as the professor’s house is burned to the ground, off-screen, during the fire-bombing of Japan and the professor and his wife soon find themselves living in a squalid hut amidst the ruins of post-war Japan. It’s apparent that much of the budget went to recreating this era and it’s money well spent.

Yet, even in these reduced circumstances, the professor’s wit and good nature haven’t left him. He’s sad that he lost his books and that they had to leave behind birds in cages to burn in the fire, but he’s also philosophical about it all. One of his idols lived in a mountain hermitage in circumstances even more extreme, so he bears it with good nature. He’s still active and applying his wit to discourage public urination. He’s afraid of thunder to the amusement of his former students. Kurosawa deftly paints a picture of a truly unique and gentle man even in trying circumstances.

When the professor’s former students offer to pool their resources to build him a house, he considers that he would like a pond, but one where the fish will not have to bend their backs much because of the constraints. He conceives of a pond which is a circular ring around a central island, where the fish can swim round and round forever without striking land or bending their backs much to turn. It’s partly amusing, but also partly out of empathy between the professor and animals.

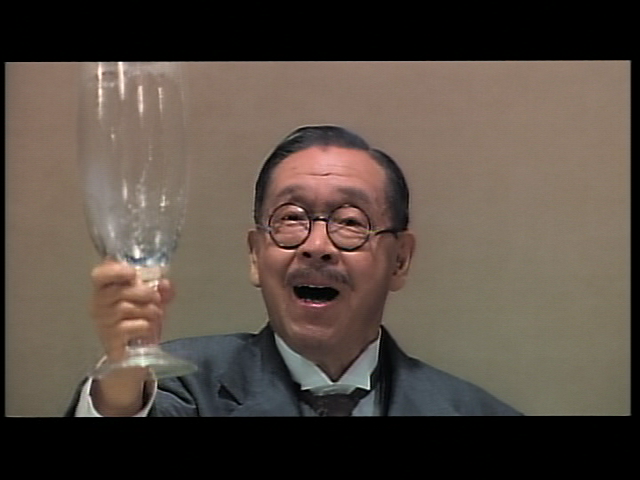

Before we get to the new home, the seasons pass, in a wonderful little set of scenes, and there’s a birthday party to be held for the professor. The students call it the “maadha kai”, which derives from the traditional cry for hide and seek in Japan. Seekers cry out “maadha kai” which means “are you ready?” and the traditional response is “madadayo” which means “not yet.” Obviously, in this context, the call and answer is about death and living on. And the professor answers resolutely “not yet” and downs an enormous glass of beer, in one go, to demonstrate his vitality.

If a film like Madadayo has a set piece, this birthday party is it. It’s a big, raucous affair with speeches, some serious, some comic, songs, a shot where Kurosawa visually represents the professor with a halo as if he’s a Buddha or a saint, and even an improvised conga line dance with the professor wittily summing up the state of the post-war nation. It’s a long, complicated scene that Kurosawa pulls off with panache. The old master still had it in him.

I think it’s also reasonable to believe that this scene represents Kurosawa’s feelings on the blossoming of his career in the post-war period. Unlike the first birthday party, which is constrained and interrupted by war, there’s a real sense of freedom and cutting loose in the scene. When the party perhaps gets a little too raucous and the American MPs are called in, they look on in amusement instead of shutting the party down, which might be a subtle commentary on the role of American censors in post-war Japan.

After the party, when the professor’s new home comes to fruition, we see another selfless act on behalf of the professor when the adjacent landowner refuses to sell to a man who wants to build a home tall enough that it would block the sun from the professor’s new home. Of course, the professor’s students decide to help out the landowner, but it’s another bit of sacrifice towards the professor.

Which brings up the big problem of the film, is the “solid gold” professor worth all of this fuss? It’s accepted that he was a great teacher, but it’s not shown in the film. A few witticisms and a winning personality don’t make a person a great source of inspiration by themselves. Perhaps that’s simply Japanese heritage showing. I don’t expect a Japanese audience to understand all the cultural heritage implicit in the image of Mark Twain, and there’s no reason for an American audience to understand all the cultural heritage implicit around the image of Hyakken Uchida. In that respect, the film doesn’t travel as well as most of Kurosawa’s works to western audiences and that may also explain why it didn’t get a proper theatrical release in North America.

The film also doesn’t have an overriding plot and it starts to feel like a bit of a liability after the professor moves into his comfortable new home. He’s a successful author, well loved, and there aren’t many outside forces that can impact him like World War II. So the big event of the second half of the film is the professor losing his beloved cat, even perhaps seeing premonitions.

It’s to Kurosawa’s credit as a director and Tatsuo Matsumura’s credit as an actor that this segment still works despite the non-existent stakes. Kurosawa expands the scope of the film so that we see people being kind and trying to help and crank calls to show how a person’s troubles can bring out the worst in people. We see hopes raised and dashed. I don’t want to dismiss anyone’s attachment to a pet. One should become sad if your pet is lost or dies. But, to become practically paralyzed by that loss is perhaps a retreat into pure sentimentality or even childishness. Perhaps that’s precisely the point Kurosawa is making about old age, how it can reduce one back to the state of a child.

Fortunately, Kurosawa doesn’t end the segment with a teary reunion between the professor and his cat. On the contrary, another cat sticks its head under the fence and is quickly picked up by his wife. A loss is filled and they all move on. Life moves on even if you don’t want it to.

The film then jumps ahead to one last birthday party, this one set in the early 1960s during the height of Japan’s economic recovery. The professor is now truly an old man and his glass of beer is somewhat smaller in a bit of obvious symbolism, but the professor is still able to finish the beer and shout “madadayo”. The party and Japan have changed. Now there’s room for wives and family at the table and children and grandchildren attend to fete the old professor.

Kurosawa made this film as an old man, and you can see Kurosawa and the professor merging at this point. Kurosawa even quotes from himself a bit as the children wheel out a birthday cake in the manner of the opening wedding feast from The Bad Sleep Well. This birthday party symbolizes Kurosawa as an elder statesman of cinema with a large extended family all inspired by him. And it’s essentially been that way since the early 1960s which the party clearly takes place in.

The professor/Kurosawa makes a speech to the children, but it may as well be to the audience, instructing them to find something that they love doing and keep working at it. It will be a career and a treasure to them. That’s clearly Kurosawa speaking of his own career as a filmmaker and it’s hard not to get choked up by the sentiment that he found something he truly loved doing. If this film and speech functions as Kurosawa’s goodbye, he says it in a truly uplifting way. In essence, Kurosawa gives himself a happy, fully satisfied ending.

But, amidst the revelry, the professor over-exerts himself and is carried home to rest. The doctor assures the worried former students that the professor will recover after sleeping it off, but at his age who can truly be sure? The former students decide to hold vigil and wonder about the dreams of their professor. Perhaps to their relief, they hear the professor yell “madadayo” in his sleep.

Fittingly, considering how it was a continuing motif of the last part of his career, we see the professor’s dream. In the dream, he’s a young boy playing hide and seek yelling “madadayo” to the seekers’ calls of “maadha kai.” We never get to hear the final cry of “not yet” or “I’m ready” as the child in the dream is distracted by the sky changing into a Kurosawa painting. Kurosawa leaves the ending open, perhaps the story and his filmmaking could continue for years, but ultimately the cry of “I’m ready” will be heard. But there are wonders to be seen in the meantime.

Madadayo doesn’t have the filmmaking bravura of earlier Kurosawa works such as Kagemusha, Ran, or even Dreams, but it has a simple emotional power anchored by a fine performance by Tatsuo Matsumura and the rest of the cast that makes it a worthy final addition to his filmography. There’s not much at stake and it doesn’t translate as effectively as many of his other films, but it’s a well made film and really makes an impression after a trip through his filmography. As a goodbye, it’s truly effective.

Kurosawa continued to work on a screenplay for the film The Sea is Watching, but he was in ill health and any hopes of directing the film soon evaporated. The Sea is Watching was eventually made after Kurosawa’s death, so he left very few projects unfinished, even if his hopes of dying on a film set never came to pass. Kurosawa died after a stroke on September 6, 1998, a day I remember, at the age of 88. There’s no tragedy in an old man dying, but it still was a moving moment for me and thousands of film fans. Thirty thousand people attended Akira Kurosawa’s funeral which is testament to how much impact his films left on the world. It’s an impact that is still felt today, even on those who don’t know the name of the director that influenced much of world cinema.

It’s been a long journey to this point and I found myself inspired by much of what I encountered on the journey. I knew Kurosawa, but I discovered a lot more in the course of the project. The length of journey is a testament to the depths of his films and what they inspired in me. But, in shorthand, here’s my summarization of Kurosawa.

Kurosawa had the eyes of a painter, and painted the silver screens of the world.

Kurosawa had the spirit of a warrior, and created some of the most exciting adventures ever witnessed.

Kurosawa had the social conscience of a priest, and created moving portraits of Japanese society and the common ties of humanity.

Kurosawa had the probing mind of a philosopher, and used his tools to explore the complexities and paradoxes of the world.

Kurosawa left us all a treasure of his work. A treasure that will live on long after everyone reading this.

Next Time: AFTERWORD