THE MEN WHO TREAD ON THE TIGER’S TAIL (1945)

As World War II was dragging to an end, Kurosawa wanted to make his next movie, a samurai epic, which the Allied bombing campaign was making impossible. A studio film with many sets or other lavish production values was out of the question. In a stroke of resourcefulness, Kurosawa found an answer. He wrote a script in one night that required one set and otherwise could be filmed on location in forests and meadows away from the bombing campaign.

Kurosawa’s story is an adaptation of a 12th century incident. Lord Yoshitsune has a falling out with his brother and must escape into safer lands. His retainers, including his chief bodyguard Benkei, disguise themselves as monks, with the Lord as a porter, and must submit to close questioning at a checkpoint where every question and answer could lead to

their capture. Finally satisfied, the steward of the barrier allows them to leave, but Lord Yoshitsune comes under suspicion as they prepare to depart. However, Benkei beats Yoshitsune, in complete contradiction to the role of master and servant, and completes the ruse allowing them to escape. The story has been a staple of both Kabuki and Noh, as the plays Kanjincho and Ataka, respectively. Giving the outline of the story is a bit like giving the outline of Hamlet.

It’s a relatively simple story and the film reflects that clocking in at a trim 59 minutes. Given the ornate traditions of Kabuchi and Noh, which the film reflects, a straight adaptation would likely be something very static, full of ceremony, and a very po faced celebration of the feudalistic way. Kurosawa doesn’t quite give us a straight adaptation,

he adds a significant character, a lowly porter played by comedian Kenichi Enomoto , a Jerry Lewis / Jim Carrey rubber faced type, and then sets out with his dynamic style not to subvert the traditional story, but to add layers, contradictions, and nuance. It’s a minor movie in Kurosawa’s canon, but it’s still a remarkable one in many aspects.

Right from the start it’s recognizable as a Kurosawa picture. The first shots are looking straight up at trees moving in the wind. It’s a precursor to Rashomon.

Soon the camera pans downward to reveal men following a trail through the woods. These are clearly men of ability and determination as they stride with purpose, a precursor to Seven Samurai. At least until we’re introduced by a cackling laugh to Enomoto’s porter, who wants to talk about the weather and other trivialities. In contrast to the stoic faces of the disguised samurai, you can read every emotion and thought on Enomoto’s face and nothing is hidden.

They stop at a clearing to rest. Enomoto prattles on, engaging in helpful exposition, while the stoic men rest. Through his prattling, Enomoto puts two and two together and realizes just who he’s travelling with. It’s at this point that Benkei (Denjiro Okochi) turns around and fully reveals himself. And the movie fully reveals its dual nature. Benkei and the samurai are marked contrasts to Enomoto. The acting style is very deliberate and subtle, where Enomoto uses his full face, Okochi is content to use subtle gestures and glances, as well as an even speaking style. Drums and flutes play on the soundtrack along with songs. These samurai, with Takashi Shimura among them, are in full Noh / Kabuki ceremonial tradition.

Given that their pursuers are looking for seven priests, they decide to disguise Yoshitsune as a porter. In one of Kurosawa’s more clever bits, you really see very little of Yoshitsune, mostly hidden under a large sedge hat, until the end. They set out for the barrier, determined to bluff their way through. The samurai want to fight, but Benkei wisely points

out that they’ll have many more barriers to get through and it’s important that the disguise work. (Benkei, in contrast to the porter and later Kambei in Seven Samurai, will almost always know the right thing to do.) The porter, perhaps curious to see how this drama plays out, tags along. And, in their arrogance, the samurai dismiss the porter’s potentially helpful advice as to how Lord Yoshitsune should carry a pack, for instance.

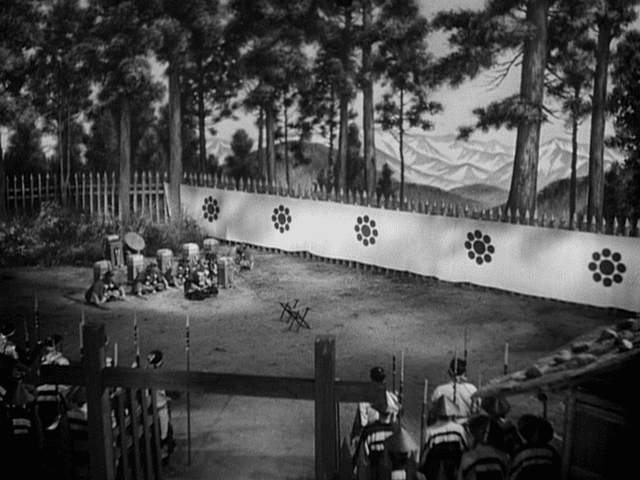

They arrive at the barrier for what is undoubtedly the centerpiece of the movie.

The steward of the barrier Togashi (Susumu Fujita) backed by an obviously villainous second in command, engage Benkei in a long series of questions, where any misstep in answering will call down the surrounding guards upon them.

This sequence really shows Kurosawa’s command of the camera and editing suite. It’s a talky scene, but it’s not a dull scene as the camera glides around and the cuts keep the scenes from flagging as we see the various reactions. It’s a scene worthy of Hitchcock or something Tarantino would attempt where every question is a potential trap. Togashi tests Benkei on all points and it’s clear he’s not a fool. It’s a different role from Sanshiro Sugata and Fujita has just the right mix of authority and conflict about his role. There’s clearly the suggestion that Togashi is not fooled at all, he smiles a lot as if amused by the show he’s witnessing, but may let them go anyways out of admiration for their dedication and honor — provided that they play their parts well. It’s a nuance that makes the character interesting instead of merely a guy that gets duped. It also suggests that Benkei isn’t the perfect hero he’s made out to be.

The big test comes when Togashi asks Benkei to read the prospectus for the temple they’re supposedly soliciting funds to build. Benkei overlooked this request and attempts to bluff his way through reading from a blank scroll. In a series of cuts and camera moves, the second in command edges closer to Benkei, the camera edges closer to Benkei, and the porter reacts in growing terror to what is about to be discovered and eventually relief.

Enomoto is clearly overacting. But it’s overacting with a purpose, albeit he can be an annoying presence at times during the film and certainly isn’t one of my favorite characters. He busts up the ceremony. You have to wonder if Kurosawa thought it would be easier to sneak the tweaks at tradition past the censors by keeping Enomoto’s reactions largely non-verbal. The script may read very different than the finished product.

Enomoto is also sort of the audience’s surrogate. To this point, he’s merely been a witness and has reacted like the audience to what he’s observed. That’s shortly going to change. And that gives his character meaning and sets what has been to this point merely a traditional story about duty to one’s superior on its ear.

As in the traditional play, the ruse works. But the second in command apparently sees through Yoshitsune’s disguise. Benkei then proceeds to beat Yoshitsune as a common porter. At this point, Enomoto steps in pleading with Benkei to stop the beating and even imposing himself between Benkei and Yoshitsune. It sells the ruse completely with one porter pleading for another. The lowly porter protects the Lord. A Lord he has no loyalty to, except perhaps as a fellow human being. The story no longer becomes one clearly about doing what you can for your master, but of displaying kindness to a suffering person. The porter performs the traditional duty, protecting the Lord, that the samurai must violate.

The events leave little room for keeping the priests, and they’re allowed to pass. A short ways away from the camp the party rests and Benkei breaks down in shame. But he’s forgiven by Lord Yoshitsune who finally reveals himself.

Perhaps as tribute or as apology or simply out of kindness or as a bouquet for a good performance, Togashi sends a messenger with sake for the party. Benkei drinks deeply, perhaps to assuage his guilt, perhaps out of realization that he didn’t fool anyone, and the whole party, including the porter, drinks in celebration.

Traditionally, Benkei gets the last scene of the story. He wakes up with a hangover and proceeds to do a dance of balance. He’s the hero of the story who gets to demonstrate his mastery one last time. Not so in Kurosawa’s version. The porter wakes up and finds himself covered with a fine robe and with a purse as a reward while the party has left in the night. The final dance is left to him and the common peasant who displayed kindness is the hero of the picture. Or almost, as he can’t quite pull off the dance without a tumble. If

he’s not a “hero”, he’s a human who did something heroic and traveled with heroes, at least for awhile.

Kenichi Enomoto as the porter represents what will be a continuing trope of Kurosawa’s; the fool, perhaps owing to Shakespeare, who skewers the pomp of the upper classes. You

can see some of this from Toshiro Mifune in Seven Samurai, but it’s on full display in The Hidden Fortress and Ran. I suspect that Enomoto is what George Lucas was thinking about when he created Jar Jar Binks, to a much less satisfactory result. The difference being that Jar Jar is a fool only there to provide comic relief, while Enomoto’s porter proves crucial to the plot, attempts to supply actual helpful advice, and demonstrates that the lowest of the low can be noble and honorable in a tough situation, contrary to their perception. Enomoto’s character is a person, an extremely caricatured one admittedly, with human contradictions. Jar Jar is a cartoon, literally and figuratively.

I suspect that The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail was one of the kernels for The Phantom Menace. A small group of warriors leading a disguised noble through enemy lines with a fool in tow complete with some Kabuki visual touches are elements common to both films. The results are vastly different as Kurosawa has a story to tell with comments on the nature of humanity. Kurosawa plays his story for drama while Lucas uses the framework for action.

The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail wasn’t released until 1952, after Kurosawa had already become famous internationally. Kurosawa’s skewering of tradition didn’t sit well with the Army and it was too traditional for the Allied occupation. As a result, it didn’t pass censorship from either side of the war. Still, it’s an entertaining, interesting film. Kurosawa took a story that could have been simply a celebration of martial duty and turned it into a story of unexpected kindness and humanity. There’s not much to it beyond the main story, Benkei’s fellow samurai don’t have distinct personalities, and it plays much more like a short story than an epic movie. It’s a minor work, but a very satisfying one.

It drew to a close an important phase of Kurosawa’s work. Three of his first four films are accomplished films of that era and it’s clear that Kurosawa had real talent. The next phase of his career was beginning where Kurosawa would have to deal with the more liberal Occupation censors and turn his attentions to contemporary issues instead of the period piece which he is most famous for.

Next Month: NO REGRETS FOR OUR YOUTH (1946)