A strike had stopped production at Toho Studios prior to filming The Quiet Duel and Kurosawa was desperate to get back to work as soon as possible once it ended. So, Kurosawa turned to a play penned by Kazuo Kikuta dealing with a doctor dealing with a real life issue in contemporary Tokyo. Perhaps because it was a play first, Kurosawa thought that he could quickly get started on production with just a few changes to open it up. Kurosawa obviously had great affection for doctors, and a film set in a rundown hospital with a doctor struggling with a personal and, at the time, shocking illness had an innate appeal. Plus, it was a chance to give Toshiro Mifune a chance to star in a role that was far removed from the gangsters he had portrayed in his first three films and a preemptive strike against being typecast. All of that sounds good on paper, but the screenplay to The Quiet Duel hardly plays to Kurosawa’s strengths and the results are a mixed bag.

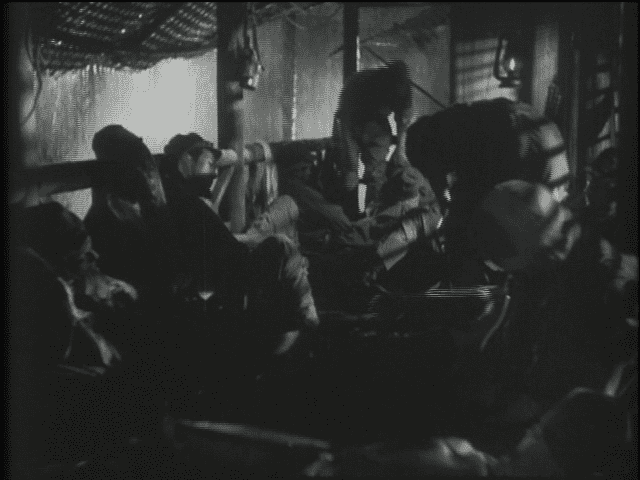

The Quiet Duel starts off as what you expect and want from Kurosawa. The opening credits are set against a background of scenes of pouring rain with pounding drums on the soundtrack. There’s mud everywhere. A truck illuminates a Red Cross sign and text reveals that it’s 1944. Men scramble through a triage packed with wounded men. Kurosawa has plunged us head first into World War II, and from the Japanese perspective which is a rare feature of cinema. Even with a few establishing shots, Kurosawa quickly establishes that it’s not a time of glory.

The cinematography is stark and full of high contrast black and white. There’s a depth of field here as well. I have issues with The Quiet Duel, but Kurosawa’s compositions and the cinematography by Soichi Aisaka aren’t among them. In fact, the shooting scheme is reminiscent of film noir which suits the moral struggles of the film.

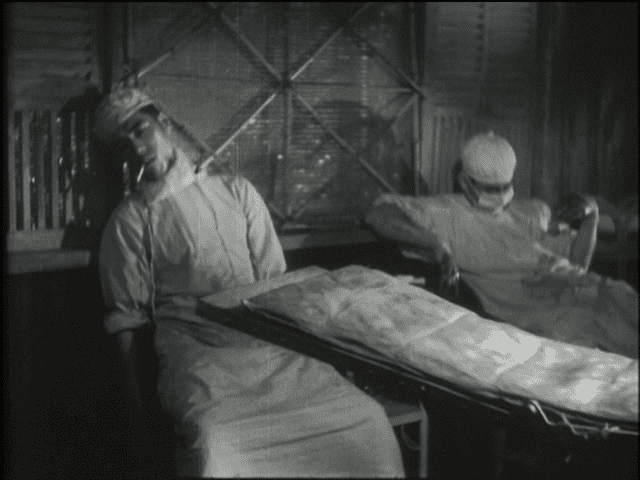

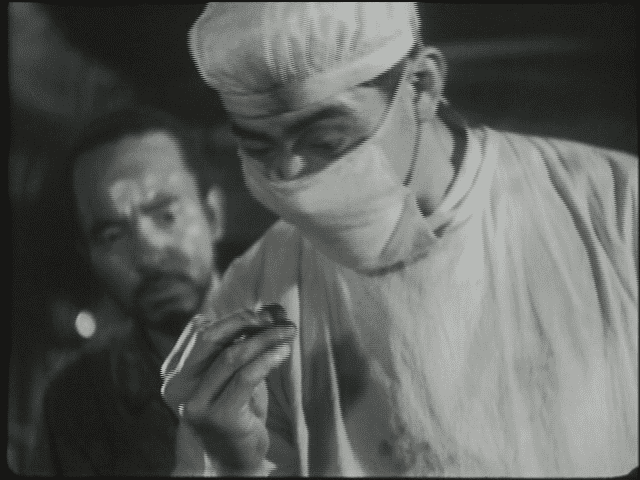

In this scene we’re introduced to a pair of doctors utterly exhausted by the endless stream of wounded they’ve been handling. Kuroswa’s introduction is clever, we see two doctors both passed out from exhaustion, and Toshiro Mifune’s Kyoji Fujisaki is so dedicated to duty that he’s passed out still wearing his surgery mask and not letting his hands droop — still ready for their next instrument. It’s an efficient character introduction as it sets up character and the fact that they’re not at the top of their game and mistakes can happen through no conscious choice. It’s also vaguely prescient of M.A.S.H.

The comparisons to M.A.S.H. continue as the surgeons are summoned to treat a patient with an abdominal wound and Kyoji struggles on despite exhaustion. Kurosawa manages to stage a fully formed scene with depth of field. The surgeons are fanned due to the obvious heat. Water drips down and is captured in pans in the foreground with the sound of the rain drops perhaps being a metaphor to the heartbeats of a patient. It’s a master class of staging which keeps the scene dynamic considering the actors can’t move from their stations.

The raindrops are distractingly noisy, the lights flicker, the heat requires Kyoji’s brow to be wiped constantly, the surgery is difficult, and knots are almost impossible to tie while wearing gloves covered in blood. It’s a well staged scene, so that when a series of simple mistakes are made it’s completely understandable. Kyoji removes a glove to tie knots. He hurriedly sets a scalpel down with his concentration on the patient. No reason he should pay attention to it.

But, when he reaches for it again, Kyoji cuts his finger. It’s a minor cut. It’s attended to quickly, but there’s a patient dying on the table so Kyoji plunges his hands back into his work and gets started. It’s completely commendable.

And he suffers for it for the rest of the movie.

There’s follow up as Kyoji overhears the recovering soldier Nakata (Kenjiro Uemura) spout off about how he’s going to be sent home because of his wound and disease. Kyoji realizes that he has become infected with syphilis and probably won’t cannot treat the disease while constantly on the move with the Army. The main thrust of this section of the movie is covered in those brief moments that open the movie and they demonstrate what Kurosawa is so good at. It’s a dynamic sequence showing characters in action. And, tellingly, it’s doubtful that any of that is in the play but simply fleshed out back story. The next sections of the movie are talky and you can see Kurosawa struggle to bring the characters inner lives to outer action.

The film jumps forward to a rundown hospital in post-war Tokyo and quickly introduces a new cast of characters. The most interesting of them, by far, is Ninegishi (Noriko Sengoku), a nurse’s apprentice from a troubled past. She’s a former dancer who had gotten knocked up and tried to commit suicide before being saved by Kyoji and offered a job. She’s cynical, not particularly thankful, and the only character that feels like someone Kurosawa would come up with.

The hospital is also a character in this section. It’s dirty and clearly has seen better days, even if it still functions. Ninegishi notes that it used to be clean. It’s a pretty clear metaphor for Kyoji as well as being an accurate reflection of the times. The photography has a crispness and a deep field of focus; if it can’t hide how stagebound the movie is, at least creates a sense of place within the sets.

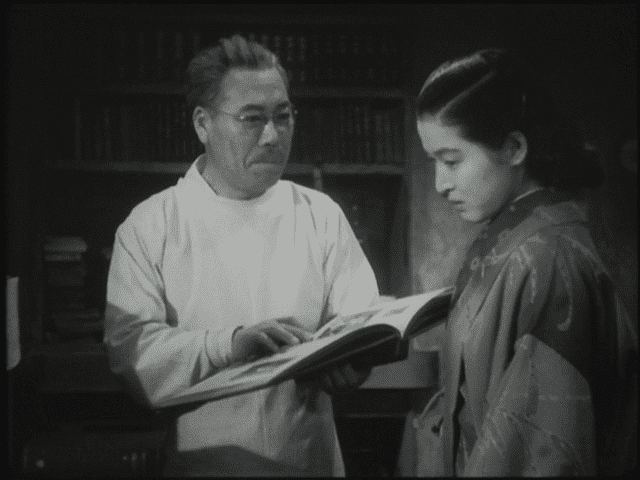

We’re also introduced to Kyoji’s father Konosuke played by Takashi Shimura. He’s an obstetrician, although it appears that he’s drafted into more general hospital work due to the shortages around him, and he’s the wise, good humored sage that Morgan Freeman has made a career of playing.

Completing the principal set of new characters is Kyoji’s former fiancée Misao (Miki Sanjo). Kyoji has hidden his infection from everyone and has broken it off from his fiancée. However, she’s still hanging around the hospital, nobly helping out, and trying to win back Kyoji’s affections. She’s less a character than a type and, unfortunately, never develops any shadings that make her interesting. Instead, she’s a prim, noble, virgin pining for her love.

Konosuke tries to rekindle their relationship by having Kyoji escort Misao home, but in a recurring visual metaphor, their relationship is like the vines of flowers that form the backdrops of their walks which wither and die over the course of the film. (There are very few nature metaphors that Kurosawa didn’t like to use.)

Kyoji eventually finds out that you can’t hide the treatment of a serious disease in a hospital as Minegishi walks in on him in the midst of treatment. And, recognizing what the treatment is for but not the cause, she feels vindicated that she has something on the “noble” doctor. Konosuke a short time later discovers his son’s disease through an overheard argument between Kyoji and Minegishi.

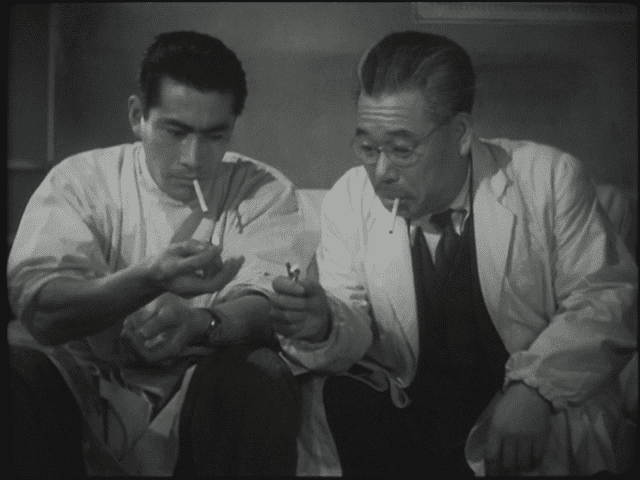

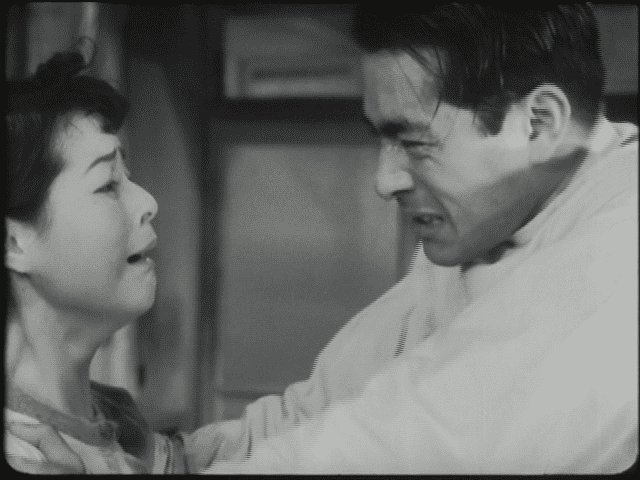

It’s not long before Konosuke gets to the bottom of what’s going on with his son as a result. And, they have it out, with Kyoji explaining that he has syphilis, before fully explaining how he got it. Konosuke’s reaction is one of disappointment, as is common with any sort of STD. You can look at the reaction to a diagnosis of AIDs in the 1980s to see how modern people react to a serious STD, and syphilis was just as serious at the time of the movie. But, when Kyoji finally learns of how his son was infected, he feels shame for jumping to conclusions. His son is every bit as moral as he assumed prior. An eavesdropping Minegishi also learns shame for jumping to a false conclusion and respect for his self sacrifice.

It’s a wonderful scene from an acting standpoint. Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura had a natural chemistry that served them well in movie after movie, even when the subject matter is quite different. It also points out the chief problem with the story– like an episode of Three’s Company, once the source of the infection is explained, the moral conflict disappears completely.

Kyoji justifies not telling Misao as it will take years for him to be cured and he has no intention of infecting her. And, by implication, she’ll not be able to bear children at that point. It’s better if she moves on to someone else.

While that’s all noble and self sacrificing from a certain point of view, it’s also enormously patronizing. The culture does change over time and you have to make certain allowances for that when viewing older movies. Still, it’s much easier to ignore cultural differences when it isn’t the central conflict of the movie. There’s no question that from a modern perspective Kyoji should tell Misao and let her make her own choice. Kurosawa is usually forward looking in his politics and morals, but this is one of the rare cases where a Kurosawa film is conservative in its message.

It also doesn’t sit well with the rest of the movie. The day to day operations of the hospital are modern. Kyoji bonds over baseball with a boy after an appendectomy. Heck, there are fart jokes in The Quiet Duel as passing gas is the sign that a patient has recovered sufficiently after an abdominal operation to take food and water. Minegishi talks openly about how she wished she had gotten an abortion. Inserting an almost Victorian sense of discretion into film that is in most other aspects modern and frank just doesn’t sit well.

It also renders the plot inert for much of the remainder of the movie. If Kyoji isn’t going to come clean now, then structurally it has to wait until the climax. That might be alright if the movie was packed with subplots and characters, but that’s not something this movie has going for it. Instead, we have noble people suffering nobly. If it was a modern film, it would be dismissed, perhaps rightly, as Oscar bait.

The movie does its best to keep moving . It jumps ahead to winter. Minegishi has had her baby, after realizing how much Kyoji is willing to sacrifice and bear, and is studying to become a full fledged nurse. Konosuke is bonding with Minegishi over the child, perhaps as the ersatz grandchild he could have. Misao is moving on and engaged to be married. And Kyoji is still battling his disease.

The one wrinkle in the plot that does add interest is that Kyoji is summoned to the police station to treat an injured officer and he’s reunited with Nakata, the man who originally infected him. It’s at this point that we see how much Kyoji is a doctor as instead of being overly bitter he tries to help Nakata and follows up on how Nakata has been faring and if he managed to stay current with his treatments. You only have to look at the wall of the bar Nakata frequents to know that he’s not taking his medical situation seriously, although he does claim he got the all clear from a doctor.

Nakata is the flip side of Kyoji. You get the sense that he hasn’t sacrificed a thing. And Nakata’s story puts the cautionary warning that Kyoji’s restraint was the right choice. Unfortunately, it’s kind of ham handed in driving the point home.

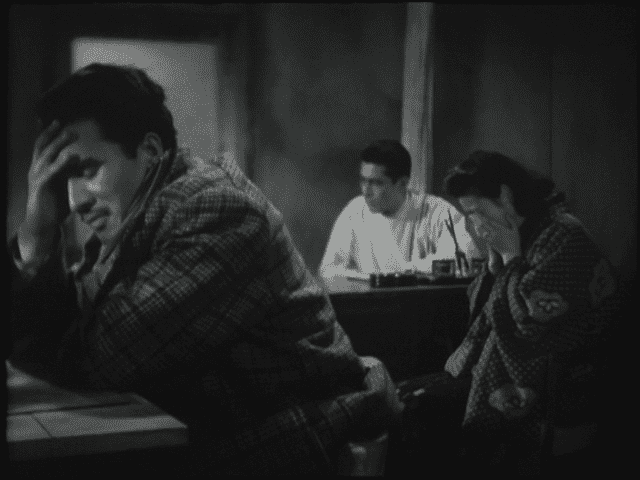

A few meetings and Kyoji is confessing that Nakata passed on his disease to him. And, Kyoji is horrified to learn that Nakata has taken a wife who’s now pregnant. Sensing the potential disaster, Kyoji discloses to Nakata that he’s infected through the same bacteria that infected Nakata, and that he’s still not cured. With that, Kyoji convinces Nakata to bring in his wife for tests and discovers that she is infected with syphilis with dire consequences for her and her baby. It’s devastating for all parties involved, but it all stems from Nakata’s selfishness in contrast to Kyoji’s selflessness.

That shot prior is also a good example of Kurosawa’s sense of composition. It could have been people sitting directly across from each other at a table. Instead, Kurosawa uses the deep focus to separate the characters across space as they’re all alone with their thoughts. This may be lesser Kurosawa, but there still are plenty of pleasures to be derived here. The screenplay may have issues, but Kurosawa still has a command of composition and acting that few have ever equaled.

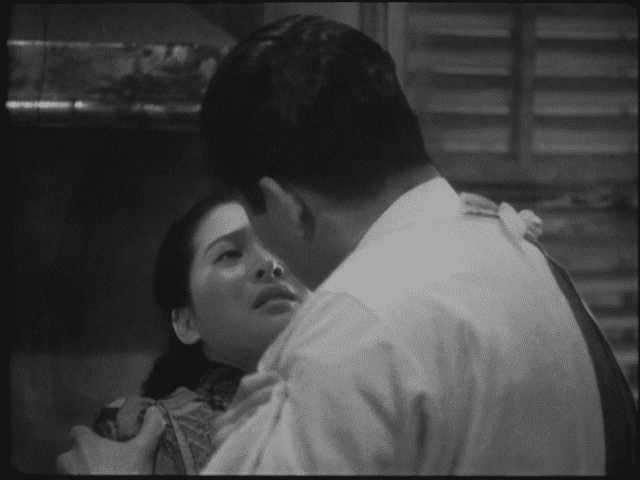

Kurosawa follows up this painful consultation with Misao visiting Kyoji and letting him know that she’s to be married the next day. It’s a painful encounter as Kyoji’s options are all but out. He loves and desires Misao, but he’s just been given a vivid reminder of what can happen if he’s weak. This is moral of this scene is obviously underlined given its place in the movie, but it’s so well acted and staged that you can sense the danger of Kyoji failing.

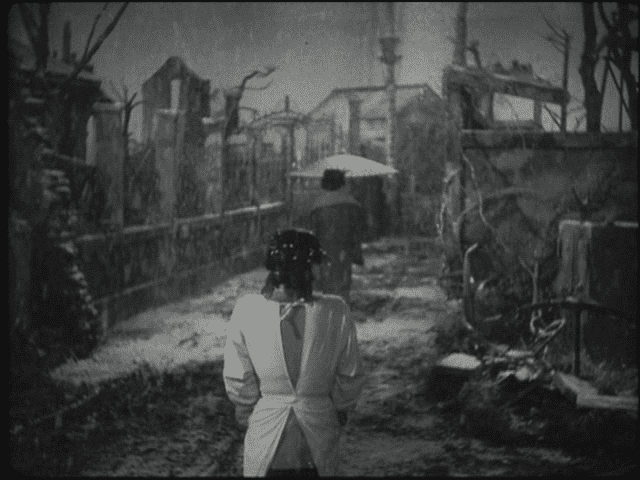

Ultimately, Kyoji resists. He’s too noble to fall. And, with that, Misao exits his life in a beautifully composed shot. Perhaps Kurosawa is a little too cute, but he adds a train whistle just to drive the point home that she’s leaving Kyoji for good.

It’s up to Minegishi to finally get Kyoji to fully open up. And explain the title. It would be easy to assume that the “quiet duel” of the title refers merely to the physical battle between Kyoji and his disease. And that would be right to an extent. But, the battle that Kyoji is fighting is also between his physical desires as a man and his moral duty as a man and as a doctor from spreading his disease further. It’s a long, tearful scene where Mifune fully reveals the depths of his feelings and his battles. Frankly, it’s a bit much given how in control he’s been throughout. Mifune is very good in The Quiet Duel giving a reserved performance with about the only showy bit being the tic where he constantly rubs his cut finger throughout the whole film. For someone who’s great at portraying fiery gangsters and samurais, his performance as a noble doctor is welcome display of his true range. But, when finally given the chance to let loose Mifune and Kurosawa turn it up to eleven, with tears, declarations right into the camera, thrown objects of furniture, etc. It doesn’t ruin a very good performance by any measure, but it’s a climax that comes off as over the top and didactic.

It does hint at a future for Kyoji. Minegishi declares that she would sacrifice her body to fulfill his desires. Kyoji won’t hear of it, but it’s clear that there’s someone that will be there for him for when he fully recovers. Someone that knows his secrets, his desires, and his shames. When Minegishi declares that she loves him and Kyoji merely changes the subject to the latest medical case that he’s attending to rather than denying her or himself the possibility.

To underline that there’s hope, Nakata’s story plays out in a lesson for what happens when selfishness prevails. And to the surprise of no one, it’s not a happy ending.

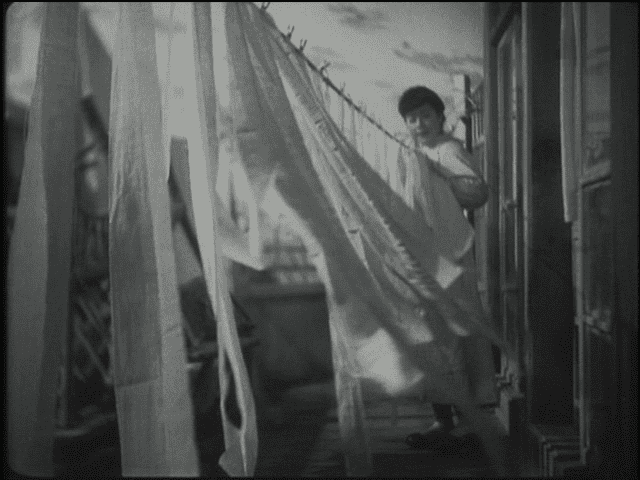

Kyoji might not have a purely happy ending either, although it’s not the depressing one the original screenplay proposed where he goes mad from his infection. Instead, he continues to treat the disease. And, Minegishi and Konosuke are still there to support him. He’s come clean and can move forward at last. Kurosawa might even engage in a visual pun as we see Minegishi at work airing the formerly dirty now clean laundry of the hospital. This is probably the first time we associate the hospital with cleanliness and it’s certainly an image of hope, as well as being a fun dynamic watching the laundry flap in the breeze. Minegishi is now wearing spotless white now too.

The Quiet Duel isn’t necessarily a bad movie. There’s plenty to admire about the cinematography, the ideas in the screenplay, and the acting. However, the main characters are just too pure to be very interesting, the hospital setting doesn’t allow Kurosawa to fully flex his muscles, and the story ends up being fairly didactic. Kurosawa was never the most subtle director and this is a story that requires a far lighter touch to pull off as it was much more suited to the style of Yasujiro Ozu.

Perhaps sensing the deficiencies of The Quiet Duel, Kurosawa dived right back into the contemporary crime milieu of post-war Tokyo. And the result is one of his best and most entertaining films.

Next Month: STRAY DOG (1949)