Kurosawa had the cinematic chops to create compelling movies out of scenarios that weren’t on their surface cinematic or were just flat out abstract. The subjectivity of truth. Meeting a production quota. Battles with disease. How one deals with the difficult realities of post-war Japan. How one deals with one’s own mortality. It’s sometimes difficult to sum up just how entertaining his movies are when you have to explain the high concept behind some of his films.

Which brings us to Stray Dog, where no allowance for a difficult concept is necessary. A rookie cop gets his gun stolen and relentlessly hunts for the thief through the mean streets of post-war Tokyo during a sweltering heat wave. If that description doesn’t get your adrenaline pumping, I don’t know what to say.

The Quiet Duel was stagey, dialogue heavy, and had long extended scenes. In contrast, Stray Dog takes off and scarcely slows down. You can tell Kurosawa was proud of the story hook since as soon as they get out of the credits he gets right to it with Murakami (Toshiro Mifune) reporting the loss to a superior and then fills in the story. Kurosawa resorts to an unusual device for himself by providing backstory, voice over narration. The voice over is pretty perfunctory, at least as translated, Murakami is a rookie, he was tired, and it’s hot as hell, but it gets the points across without need for character exposition. It’s inelegant, but efficient. It might even be a nod to the American crime films of the period with their Chandler-esque narrations, although it’s not a real good imitation if that was the intention. Either way, we’re quickly off to Murakami’s pocket getting picked on a public bus by a woman that reeks of cheap perfume.

It doesn’t take Murakami long to recognize the theft. And he’s after the man who has been passed the gun in no time. Kurosawa takes a dynamic overhead shot to set up the geography of the chase and then gets right into it.

The chase shows Kurosawa’s action chops which are fully formed. There are cuts on movement, axial cuts, tracking shots, and he uses the camera’s full depth of field for staging the scene. Of course, the foot chase ends unsuccessfully for Murakami, there wouldn’t be a movie otherwise, but it’s anything but perfunctory in its presentation.

Murakami will be doing a lot of pursuing in the film, so it only seems fitting for the film to include a foot chase early. After the chase, Stray Dog changes gears into a police procedural, certainly one of the early instances of that form and foreshadowing High and Low. We learn some things about Murakami, like Mifune he’s been discharged from the Army recently, and Kurosawa plays close attention to composition so that it’s not just two men talking to each other over a desk. Murakami quickly makes his way to checking out photos of pickpocket suspects and Kurosawa makes sure to frame the space in three dimensions with activity in the fore-, mid-, and background. A fan and Mifune’s sweat remind you that it’s stifling hot.

The search leads to the first clue. It turns out the woman reeking of cheap perfume is a pickpocket. It turns out that she used to be known for her kimonos but now is wearing modern dress (Symbolism!). Murakami and a superior are immediately off to question her. It turns out that the elder officer and the pickpocket are know each other well, probably Kurosawa making a statement on how the law and lawlessness mixed following the war, but they have no proof to hold her on and she walks out. But, instead of chalking it up as a dead end, Murakami follows her relentlessly. It’s a partly comic sequence, but it shows Murakami’s dedication, almost obsession, with his stolen gun. He’s taking it very personally as if it’s part of him that’s been stolen.

Eventually, the pickpocket gives in and points Murakami in the right direction, the gun dealers of Tokyo who recruit those looking desperate. It’s an interesting decision in that it seems to be motivated by pity and annoyance . Is that a credit to Murakami’s persistence or his desperation? Kurosawa, of course, adds his own take on this condition because immediately after the pickpocket unloads her conscience she looks at the stars again for the first time in a long time. It’s hard to appreciate that there’s still beauty in the world when you’re watching your back all the time.

What follows is a long montage as Murakami breaks out his old Army gear and beats the streets of Tokyo looking for the next link in the chain. It’s a long, somewhat experimental sequence. A montage is a tricky thing, you get ideas across but if it’s too brief the plot point looks like something easily accomplished. Kurosawa tests your patience a bit here, but it’s to the idea of showing how much effort Murakami is expending. Nothing comes easy to him. Including the sun beating down in a shot that precedes the famous shot in Rashomon of the sun among the trees.

Mifune is very authentic in this sequence as an Army veteran as he was in real life. He probably didn’t have to reach very far to give off a sense of desperation. Kurosawa captures the seamy side of Tokyo well while using every device he knows to keep the film interesting. There are lots of shots of Mifune’s desperate face, lots of shots of walking feet, and even both at the same time in one shot.

The length of the sequence has been criticized. Certainly, Kurosawa errs on the long side of the montage. But, the sequence certainly establishes post-war Tokyo as an identity, filled with lots of desperate people. Clearly, it gives meaning to Murakami’s story as he’s just a subset of the larger desperate whole.

Kurosawa layers in a lot of information. And, eventually it pays off as Murakami locates a gun dealer, who will rent him a gun for his rice ration card. In perhaps a rash move, he leaps at the first opportunity to bring in a dealer, possibly while giving the rest of the gang a chance to escape. A barred door drives home the fact that jail is in the future for the dealer. A subsequent interrogation reveals that if he hadn’t acted rashly on his own, he could have hauled in his pistol, unfired, by just waiting a little bit. Action without thought doesn’t pay off in Kurosawa’s films.

In a digression, we get a scene of Tokyo CSI. It turns out that there has been a shooting, and the bullet was from a Colt pistol like Murakami’s, driving him to further despair. Murakami, obsessed at this point, digs a bullet out of a stump where he missed on the shooting range. Turns out the grooves match which confirms Murakami’s instincts and deepens his guilt. And, again, it sends him back to the dealer for further interrogation.

The dealer is, of course, a small fish. And, perhaps less of a bull in a china shop approach would be wiser. Enter a mentor for Murakami, the experienced cop Sato played by the great Takashi Shimura. Sato is a great character in his own right, introduced sharing a popsicle in the extreme heat to get the empathy of his suspect/source of information. He’d be right at home in The Wire.

The interrogation scene is a little gem as Sato controls the situation, finds the weak point in the dealer’s façade (she’s in love with her boss), and exploits it. It’s also worth noting that the girl is played by Noriko Sengoku, who played the barmaid in Drunken Angel and Nurse Minegishi in The Quiet Duel, Kurosawa is establishing his own repertory company at this point. It turns out that the guy with the gun never got his ration card back. So, the next link in the chain is up the ladder to the boss, who loves baseball games.

Murakami and Sato quickly bond. Kurosawa certainly never met a student/teacher relationship he didn’t like and this is one of his better ones. Sato is of the pre-war generation and he’s cynical. He acknowledges Murakami’s guilt over his gun, but doesn’t give it credence as anything more than sentimentality. There are good guys and there are bad guys, and that’s that. Murakami would like to follow that advice, but easier said than done. And, this being Kurosawa, there’s a storm brewing in the background.

Then it’s off to the ballgame to round up the head of the gun dealing syndicate. This of course represents a problem on how to find and safely bring in an armed criminal in the midst of a crowd. Kurosawa uses the ballgame, which surely seems more exciting than usual with lots of hits, plays at the plate, etc., as a tension device. As the game moves along, the time to locate and apprehend the criminal becomes more problematic. It’s not quite Hitchcockian in nature, but it is an effective device. Finally, Sato comes up with a solution and the straight police procedural portion of the narrative comes to a conclusion.

Kurosawa has a tendency to split his features into essentially two sections. Consider Ikiru or Seven Samurai before and after the intermission. The second half of Stray Dog evolves into the story of two men, Murakami and Shinjiro Yusa (Isao Kimura), the man who has his gun. We see very little of Yusa, but nevertheless we learn a lot about him. Like Murakami, Yusa is an Army veteran. Both of them had their packs stolen on the way home from the war and were left with nothing. Murakami had the fortune of finding a job, while Yusa was left to wallow in absolute poverty.

It’s worth considering that Mifune was an Army veteran. One of the lucky ones who found a career after World War II. The story must have hit home to some extent given he could have easily ended up as someone desperately looking for work.

The trail of Yusa leads Murakami and Sato first to a comic encounter with Yusa’s friend who likes to think of himself as a real ladies man and then to a burlesque show and Yusa’s erstwhile girlfriend Harumi (Keiko Awaji). Kurosawa turns the heat and backstage resting area of the showgirls into almost a vision of Hell with the bodies entangled and no relief from the heat in sight. No one’s immune and everyone is suffering in Kurosawa’s world.

Harumi stonewalls the detectives and breaks down in fake tears. It’s the end of a long day and Sato and Murakami are beat. Sato knows he mishandled her, but the only solution is to try again at a later date. Meanwhile, Sato takes Murakami home and we get a glimpse of Sato’s personal life.

We also get to see Murakami’s view of the case and the sympathy Murakami feels with Yusa. Sato, of course, dismisses the similarity of the two. But, then, he’s of a different generation. The post-war (après-guerre) generation is the generation of Murakami and Yusa. Sato’s been a cop long enough that he’s forgotten that he too perhaps faced a choice. He made his choice and never looked back. To him, criminals are now like dogs, stray or mad. Murakami is, of course, familiar with desperation. And, so, every bullet that Yusa fires is a bullet that Murakami could have if things had gone differently. Or, at least, so Murakami imagines. And, as the bullet count escalates as a murder occurs and there’s no going back for Yusa. In response, Murakami grows more desperate in his search. If he can’t redeem Yusa, perhaps he can redeem his own part.

At this point there’s no turning back for Murakami and with a murder, there’s an added sense of urgency. They’re only real lead is Harumi and they track her down to her home. Turns out that she has seen Yusa, and while Sato tracks down a lead, Murakami sticks with Harumi in case that Yusa shows up.

While Sato investigates, Murakami and Harumi get to the heart of the matter which is the desperation of many of simply wanting a better life in an unfair world. Is it too much to ask for a pretty dress after how much they’ve suffered following the war? The answer is, of course, that suffering doesn’t give you the license to make others suffer. It turns out Yusa had bought Harumi a dress which Murakami goads her into wearing. It’s only by wearing it that Harumi realizes the shameful way it was acquired. She breaks down weeping and the heavens break down in rain, ending the heat wave. Of course, Kurosawa can’t resist introducing weather into an emotional scene, but he’s set it up so long that the payoff is worth it.

Murakami isn’t out of the woods yet. Sato does track down Yusa, but takes two bullets for his efforts. A Kurosawa hero can’t track down a villain with assistance, he ultimately has to do it for himself. Meanwhile, Murakami has even more reason to beat himself up.

Sato will live though. And Harumi atones for her part in Yusa’s rampage by informing Murakami that Yusa wants to meet her at the morning train so that they can escape together. Harumi’s seen the error of her ways, but Yusa has gone too far.

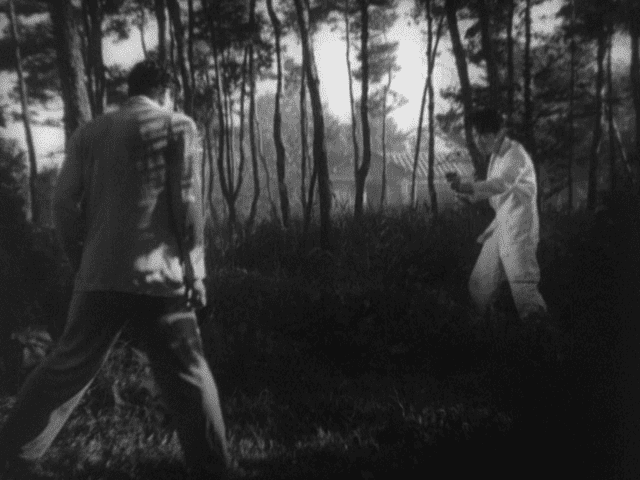

There’s a kind of clumsy voice over narration by Murakami as he deduces who Yusa is at the station. Not even the same narrator as opened the movie, which is a head scratching decision in an otherwise marvelously crafted movie. But, the misstep is small and Kurosawa gets to display all his action chops as Murakami pursues Yusa through the woods for a final confrontation. Murakami is encountering a wild version of himself and he’s only slightly less desperate than Yusa. Both of them have become wild dogs.

Kurosawa wasn’t completely happy with the final vision of Stray Dog which he had originally written as a novel in the style of Georges Simenon. Kurosawa may not have achieved the film in his head, but the final version is a great movie nonetheless. It’s gripping, exciting, well acted, expertly shot, and has a lot to say about post-war Tokyo. It’s a great police procedural in its own right and a preview of High and Low. By all accounts, it was a terrific success with critics and at the box office of the time. Today, it’s still riveting.

And, despite his misgivings, Kurosawa seemed ready to move on to other things, although he still wanted to make a movie about contemporary Tokyo. His next film again featured Toshiro Mifune, but was much less concerned about crime, medicine, and Japan’s post-war trials, but a different social ill that he felt was plaguing contemporary Japan.

Next Month: SCANDAL (1950)