I’d like to thank Matt for allowing me a platform for a new feature, a look at Akira Kurosawa’s films from beginning to end in chronological order. The inspiration for this was one of those Facebook lists of how many films of random category you’ve seen. And the result for me was surprising in how many of Kurosawa’s films I haven’t seen. Most, admittedly, are not his acknowledged masterpieces, but are still worth seeking out.

So, a journey begins to correct that deficiency. With a goal of once a month, I intend to review Kurosawa’s entire director’s filmography, all 30 films. In conjunction with the latest High and Low (Brow), what better place to start than the beginning? (If you want to follow along, a good starting place is Criterion’s Eclipse Series 23: The First Films of Akira Kurosawa and Eclipse Series 7 – Post-War Kurosawa Box. Or, if you really want to show off, AK 100: 25 Films of Akira Kurosawa (The Criterion Collection).) For the first time, all of Kurosawa’s films are readily available on DVD in the US following those recent releases. Also, Donald Richie’s The Films of Akira Kurosawa is an invaluable resource.

SANSHIRO SUGATA aka JUDO SAGA (1943)

Kurosawa was born on March 23, 1910 to a moderately wealthy family. His father was a descendant of a samurai family and was a director in the Army’s Physical Education Institute. His father was also fairly progressive in attitude towards the west and encouraged studies in that direction and movie watching.

In that upbringing, Kurosawa developed an interest in art. He was a left-wing artist in the 1930’s but became disillusioned over the overt politics in the art scene of the time and never made much of a living. In 1935, Kurosawa answered an ad from the soon to be Toho Studies for assistant directors. The ad called for an essay on “the fundamental problems of Japanese film and how they may be overcome”. Kurosawa, somewhat cheekily, argued that if problems were fundamental, then they were impossible to overcome in his essay. Perhaps to his surprise, he got a job regardless and worked on an assistant director on 24 films, the last of which Uma (Horse) he claimed to have done more than the actual credited director. He also took up screenwriting to supplement his income, and was good at it.

Following Uma, everyone pretty much acknowledged he was ready to take the step to director, they only had to find the right source material. And something that would pass muster with the war time censors. Kurosawa eventually settled on Tsuneo Tomita’s novel regarding the birth of Judo and the rivalry between Judo and Jujitsu and Kurosawa was able to secure the rights, right before a host of other filmmakers. Kurosawa then went about writing the screenplay, as he would do for all his movies, filmed it in the winter of 1942, and released it in March 1943, after a tussle with the censorship office over the film being too “British-American”. Eventually 18 minutes were trimmed and lost.

That’s all academic background. What’s astonishing about watching the movie is how fully-formed Kurosawa already is in his first film. The first scene is an tracking shot as the camera tracks down a busy, Japanese town street and then turns left into an alley, while women sing about having to walk a narrow road. With a 180 degree cut, it’s instantly revealed that the tracking shot was really a p.o.v. shot of Sanshiro Sugata (Susumu Fujita ) who now has his way blocked in the narrow alley. In a matter of seconds, Kurosawa has introduced one of the key themes of the film and indicated the character arc of the main character, while also being dynamic visually. This efficiency will be a hallmark of the film and Kurosawa’s career.

Sanshiro is looking for an instructor in jujitsu and is directed to a nearby school. There he falls in with a group of martial artists. They’re grousing about a rival instructor and Sanshiro asks the next key theme of the film “What is judo?”. Knowingly, these men don’t have an answer to that question. And, to the film’s credit, it doesn’t answer that question in a long stream of exposition, but allows the viewer to learn through the experiences of Sanshiro Sugata. But, to make it short, what I take from the film is that jujitsu is simply martial arts for the sake of martial arts, while judo couples martial arts with a respect for life and humanity.

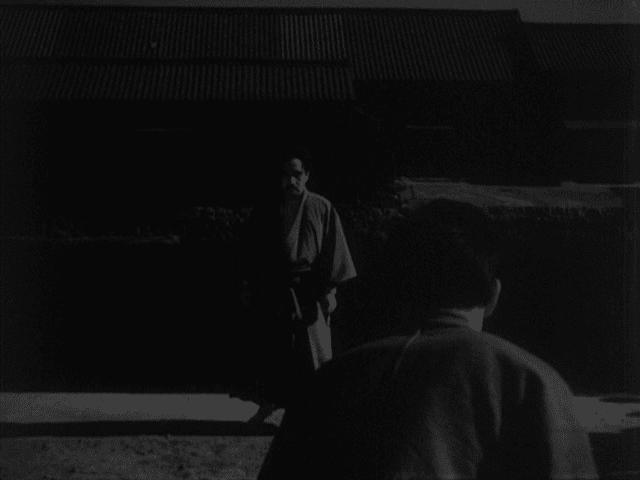

The jujitsu group decides that they’re going to teach the judo instructor, Mr. Yano (Denjirô Ôkôchi), a lesson and set out to ambush him at night. They assault his rickshaw driver and then prepare to attack the middle aged man by the river.

They get more than they bargained for as Yano proceeds to toss them all in the river. There’s a wonderful series of tracking shots between each successive attack on Yano as you see the confidence of the group of jujitsu experts evaporate and Sanshiro’s fascination grow.

At the end of the ass kicking, Sanshiro asks to be taken on as Yano’s student and replaces the rickshaw driver who ran off. Sanshiro kicks off his shoes and we essentially get a training montage. But, it’s nothing as clumsy as a long stream of exposition explaining judo, but a symbolic montage as we watch Sanshiro’s abandoned shoes get beaten up as the seasons roll on.

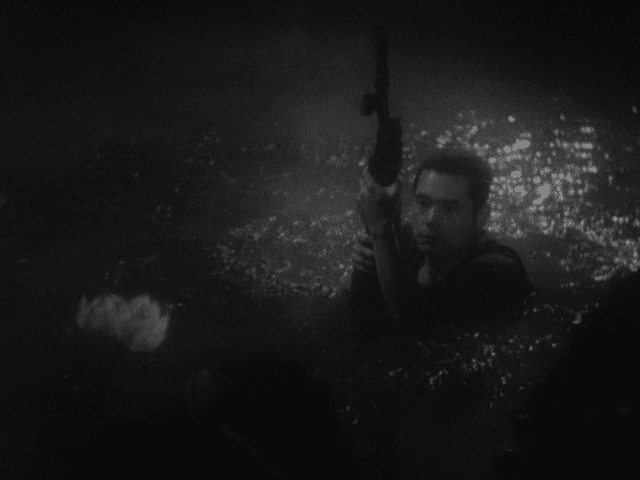

Our next scene with Sanshiro finds him in a street brawl over an alleged insult. The aftermath finds Sanshiro begging forgiveness from the gravely disappointed Yano. The centerpiece of the whole film follows as Sanshiro Sugata throws himself in a freezing pond and stays there throughout the night to show his devotion. Or to die there if he can’t be forgiven. Sugata is reborn there symbolized by a lotus flower blooming in the night.

Critics rightly point out that lotus flowers don’t bloom at night, but that’s mistaking realism as trumping symbolism and beauty. (Later, the villain will use a lotus as an ashtray.)

I won’t give a blow by blow of the rest of the movie, but have done so here just to demonstrate Kurosawa’s command right from the outset. The first act is pretty much a complete film unto itself, quickly demonstrating Kurosawa’s mastery. And, frankly, although the rest of the film is good and contains some terrific sequences, the opening act is easily the strongest part of the film.

The plot kicks in at this point. With Sanshiro firmly on the right path, the judo school crosses paths with the villain of the film Gennosuke Higaki (Ryunosuke Tsukigata), a total slime dressed in western clothing. (An insistence from above for wartime.) Due to Yano’s restrictions, Sanshiro isn’t allowed to fight Higaki, and the promised duel between the two is the driving promise of the rest of the film. Higaki is a student of Hansuke Murai (the great Takashi Shimura) who leads a rival school. Sanshiro unknowingly crosses paths with Murai’s daughter, Sayo (Yukiko Todoroki) and their meetings on the temple steps is one of Kurosawa’s visual highlights. Particularly their first meeting in the snow.

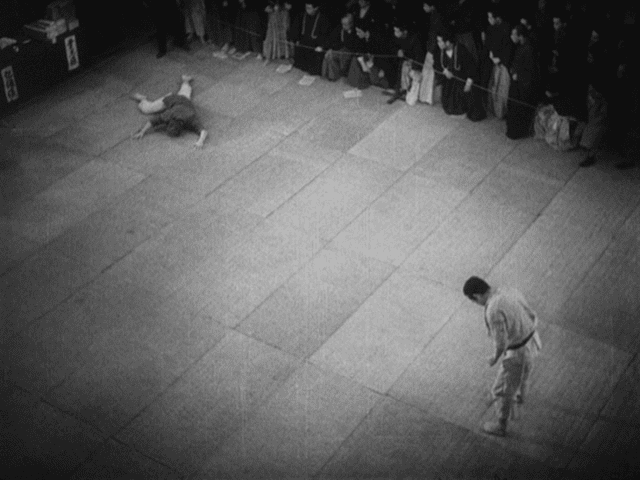

Eventually the Hansuke Murai and Sanshiro Sugata meet in a match. The middle aged Murai not being a match for Sanshiro. But the match, as centerpiece, is a terrific set piece. Tense, funny at points, exciting, and then touching as Hansuke accepts his defeat. It looks great too.

The aftermath shows Sanshiro’s growth. He grows closer to Hansuke and Sayo and takes the place in their lives that Higaki hopes to occupy. Of course, Sanshiro is worthy of that spot, Higaki is not. Higaki challenges Sanshiro to a duel on a wind-swept mountainside for the climax of the picture. Nature dominates man throughout that sequence.

The wind howls and clouds sweep across the sky at this climax, a feat of meteorology exactly matching the needs of the picture.

What’s most striking about Sanshiro Sugata is how recognizably a Kurosawa movie it is. The theme of a man (student) setting out on a journey to learn what life is all about is seen throughout Kurosawa’s filmography. And, you can see the “western” influence as the story emphasizes the individual finding his own way through life, not in finding meaning through allegiance to a feudal master. The compositions are painterly. The action has a bravura to it. Wipes are frequently deployed, often with a bit of playfulness (my favorite being a wipe with a man being thrown violently into a wall immediately following the wipe.) There are montage sequences, tracking and panning, axial cuts, cutting on action, slow motion sequences, and a relentless momentum to the film. Perhaps most importantly, Kurosawa knows when an image is all that’s necessary and the film isn’t particularly talky. There’s not a moment wasted. Kurosawa uses weather too. The final sequence takes place in an epic gale, but wind presages earlier matches (with a cut that brought a smile to my face as Kurosawa cuts from flags flapping in the winds to fans flapping to cool audience members of a match. Weather is used to show the passing of time (sometimes beautifully as when the snow falls on Sugata and Sayo on the temple steps). Heck, Sanshiro even rubs his head in a manner before a match that will presage Kambei’s tic in The Seven Samurai. Heck, there’s a cry of “madadayo” (Not yet!) in the film’s climax which will be the title of Kurosawa’s last film.

More seeds of greatness to follow include the fact that the great Takashi Shimura has a part in the film. It’s a part that shows off many of his strengths, his humor, his humanity, and his dignity. It’s the beginning of a lifetime partnership between Shimura and Kurosawa lasting until Shimura’s death in 1982. Shimura would eventually appear in 21 of Kurosawa’s 30 films and has one of the great filmographies of all time appearing in Kurosawa’s films, other classic samurai films, Kwaidan, and many of Toho’s giant monster movies including important parts in the first two Godzilla films.

Susumu Fujita is Kurosawa’s first leading man and his skills fit the needs of the picture well. He’s rugged and handsome, but he’s also able to embody the more soulful elements of Sanshiro. He’ll be a recurring presence in Kurosawa’s early filmography, although pushed out of the way by studio politics and the emergence of Toshir? Mifune after the war. He’ll later return in supporting roles and will appear in eight of Kurosawa’s films total.

There are minor flaws, of course. Nobody counts it among Kurosawa’s later masterpieces. There are cuts to men on wires to simulate them being thrown through the air that don’t work and don’t match the recoveries. The villain is obvious and shallow, and dressing him in western garments (at the army’s request) makes him less potent as a symbol of jujitsu’s limitations. The supporting characters aren’t as strong as they could be. Etc.

But it’s still a thoroughly enjoyable film with some great imagery, beyond confident direction, and a story with some depth. At the end of it, you can only conclude that there’s greatness ahead for this new director.

Even though the censorship office had problems with Sanshiro Sugata, critics and audiences did not. It was a success, and got his career as director off to an auspicious start. However, wartime needs would prevail over personal preference and Kurosawa was quickly employed to make a propaganda film. We’ll see how that turns out next month.

Next Month: THE MOST BEAUTIFUL (1944)