Akira Kurosawa hadn’t had a flop in over a decade when he made Dodes’ka-den, yet he was in need of a comeback. His production company had gone belly up in the fallout from Tora! Tora! Tora! and he hadn’t made a film in half a decade, after making a film every year in the previous 20 years. Moreover, a new wave of Japanese filmmakers had taken hold and Kurosawa was seen as the old guard, no longer in demand. Especially at his price.

Kurosawa finally settled on another adaptation of the stories of Shugoro Yamamoto, which had previously proven so successful with Sanjuro and Red Beard. With a film scenario devised by the Club of the Four Knights, which consisted of Kurosawa, Manaki Kobayashi, Kon Ichikawa, and Keisuke Kinoshita, Dodes’ka-den was to be another ensemble film centered around the lower class, stringing several vignettes together in a callback to Red Beard and The Lower Depths.

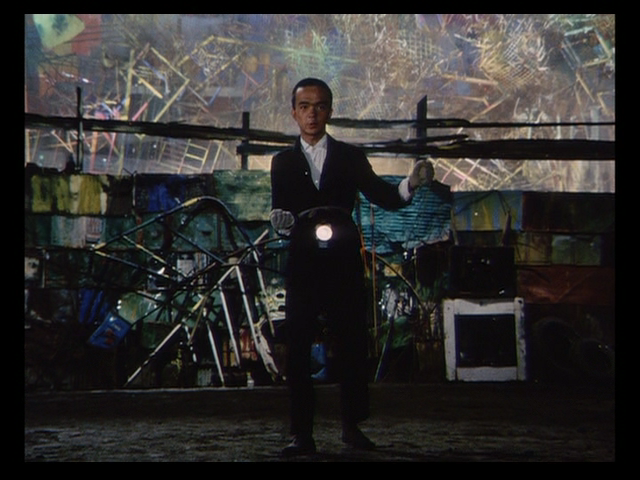

The film opens in an uncharacteristic way for Kurosawa, not merely because of the striking color and using a restricted aspect ratio (apparently because Kurosawa thought the colors would be more striking that way). Kurosawa normally is in a hurry to plunge into the story, but Dodes’ka-den opens with something of a prelude in the home of a train obsessed teen Rokuchan (Yoshitaka Zushi) and his mother, who is praying for him. Their hovel is complete with a wall of train drawings drawn by Kurosawa himself. It’s soon evident that Rokuchan is mentally deficient and escapes from day to day concerns through imagining that he drives a train. Kurosawa enhances Rokuchan’s imaginations through actual sound effects. With repeated chants of dodes’ka-den, dodes’ka-den, which emulates the sound of a train, Rokuchan jogs around the nearby junkyard / shanty town to the jeers of the local children as the “trolley freak”. But Rokuchan is lost in his own world and immune to those jeers. Rokuchan’s escape from a difficult reality via fantasy is a recurring theme of the film.

To me, Kurosawa gets off on the wrong foot. There’s nothing wrong with being eccentric and quirky, but the opening comes off as cloying and sentimental. The opening is much too long at over 12 minutes as the “trolley freak” is more connective tissue between the individual stories which make up most of the film than a story unto itself.

But, as the “trolley freak” chugs through the shanty town, Kurosawa takes the opportunity to jump off and introduce most of the cast of characters. A Greek chorus of women at the proverbial well, here a central water spigot, fills the audience in on what they need to know. It’s here that the film, without a central driving narrative, starts to find its voice.

A breakdown of the characters includes:

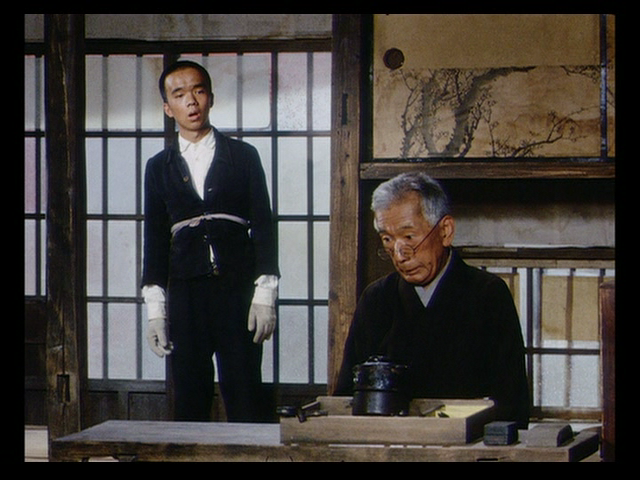

1) Mr. Tanba (Atsushi Watanabe), the local tinker and the wise old man of the junkyard community.

2) The bumbling day laborers Hatsu (Kunie Tanaka) and Masuo (Hisashi Igawa) and their respective wives Yoshie (Jitsuko Yoshimura) and Tatsu (Hideko Okiyama). Both couples and their homes are color coordinated with Hatsu and Yoshie wearing red and blue and Masuo and Tatsu wearing yellow and green.

3) Shima (Junzaburo Bani), who suffers from an absurd comic tic during periodic seizures, lives in the shantytown but seems to have a respectable job. Shima, fortunately or unfortunately, is not alone as he has a shrewish wife (Kiyoko Tange).

4) In a nearby shanty lives Misa (Yuko Kusonoki), mother of half a dozen kids, all by different fathers, and her good hearted husband Ryo (Shinguke Minami) who is seemingly unaware that he’s not the father of his children. Ryo makes brushes, and Misa flirts with men.

5) Katsuko (Tomoko Yamazaki) slaves away making and selling artificial flowers for her lazy uncle Kyota (Tatsuo Matsumura) while her biological aunt Otane (Imori Tsuji) is in the hospital. Her uncle spends his days drinking and insulting Katsuko. Katsuko’s only friend is the delivery boy Okabe (Masahiko Kametani) who is clearly smitten with her, even as she seems non-committal to him.

6) Wandering wordlessly from his shanty through the little community is Mr. Hei (Hiroshi Akutagawa) who shuffles along like a zombie lost in his own past.

7) Finally, on the outskirts even of this community, there’s the Beggar (Nobaru Mitani) and his Son (Hiroyuki Kawase) who subsist on scraps and are lost in their own imagination creating a great home on a hill. A home that Kurosawa illustrates through some artful interstitial work.

It’s around these characters that Kurosawa spins the vignettes of the film. Most, but not all, being an examination of the comforts and dangers of fantasy as an escape from reality. It’s a distinctly different film for Kurosawa in many ways, with no driving narrative and without building to a singular statement. Many of the vignettes are little more than illuminations with setup and resolution and very little in between.

It’s also a film that’s very different in style from what Kurosawa had made earlier. It’s not just the addition of a vibrant color palette and the return to a narrower aspect ratio. Kurosawa, partly due to lack of funds, employs zooms and pans in place of more complex shots and camera movements and achieves a more spontaneous style of film making in the process. His long takes, however, are still very much in evidence. Normally a Kurosawa film would take upwards of six months to film, but Dodes’ka-den was shot in a month. The result isn’t necessarily better, but it shows a side of Kurosawa we haven’t seen.

Dodes’ka-den is a film of images and moments, more than plot. I’m going to try to skim over much of the main points of the plot as it’s nigh impossible to do justice to all of that. Moments stick out though. One woman, who exudes a lot more sex appeal than is typical of a Kurosawa female, tells the tale of how she went to seduce Mr. Hei. Only the attempt went nowhere once she heard Mr. Hei cry out for “Ocho” in the night, apparently his wife or former love. We get the first hint at what has turned Mr. Hei into a zombie.

A series of night time scenes follows.

The first step in the farce involving Hatsu, Masuo , Yoshie, and Tatsu advances with a drunk Masuo getting run out of his house by Tatsu and coming to visit Hatsu and Yoshie, who are also drinking. While Hatsu goes to give Tatsu a scolding, Masuo and Yoshie flirt and bond. It’s not hard to read that the same thing is happening across the way between Hatsu and Tatsu. Essentially, Kurosawa is embedding a wife swapping comedy in the midst of more serious fare which he’ll come back to periodically.

We see the Beggar’s Son beg for scraps in the colorful streets of a Japanese city. He’s given fish with the instruction to make sure that they’re cooked. We see both kindness and indifference to the poor. At the end, the Beggar’s Son returns to their home where they find themselves lost in the fantasy of a great house. Like with the imaginary train, Kurosawa resorts to movie effects to illustrate how close reality and fantasy are as he cuts to scenes illustrating the great house under construction in their imagination.

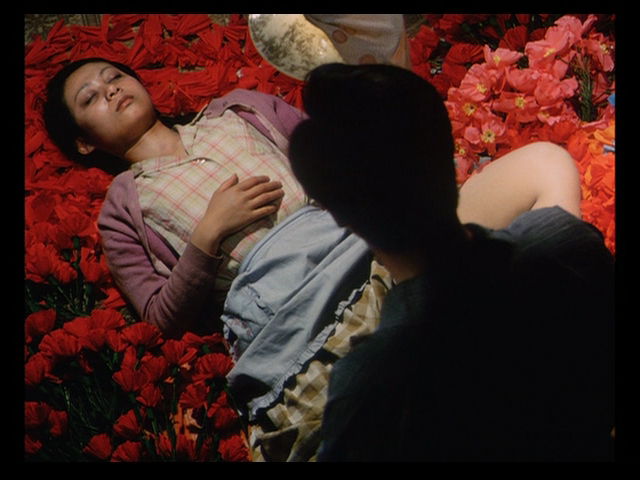

Elsewhere in the night, Katsuku falls asleep amidst the artificial flowers she was working on while Kyota sleeps the sleep of the drunken. And a thief breaks into Mr. Tanba’s house. Perhaps out of charity or practicality, Mr. Tanba directs the thief to his money and away from his tools.

In the morning, Katsuku meets with Okabe and Okabe sees the toll her uncle’s demands are putting on her. Okabe, in a fit of pique, refuses to make the regular sake delivery, a decision that will have unforeseen consequences to all involved.

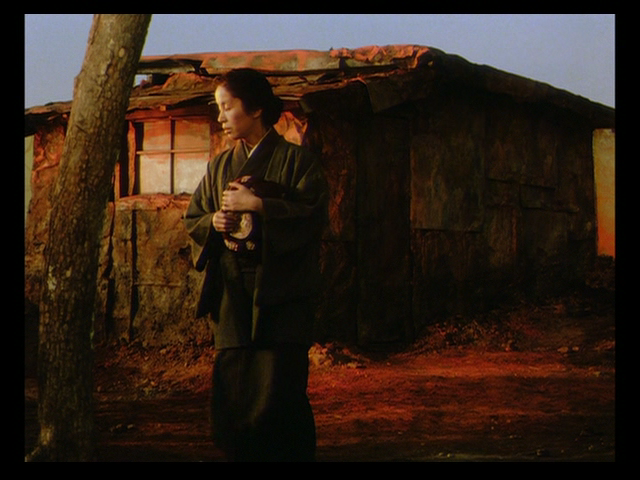

The day time scenes mostly fill us in on the rest of the large cast. Rokuchan continues on his imaginary train journeys, while his mother worries. In an important development, Ocho (Tomoko Naraoka) returns to Mr. Hei, although he doesn’t appear to notice as he’s lost in his own despair and ritualistically tears cloth to shreds. There’s a shot of Ocho by a dead tree which is important to understanding that story as Kurosawa draws a clear parallel between the tree and Mr. Hei using color. The encounter between Ocho and Mr. Hei is nearly silent, with plenty of natural lighting in Mr. Hei’s darkened shanty. It is a perfect example of Kurosawa’s visual storytelling.

In the comic portion of the story, Yoshie and Tatsu are just as good of friends as ever, with no mention at all of them having swapped husbands, which shocks the women at the proverbial well. It’s had no effect on the friendship of Hatsuo and Masuo too.

Kurosawa moves to a series of scenes set in the rain which links them visually. The fantasy of the Beggar and his Son continues as they sit under a bridge for protection from the rain imagining their great house, temporarily forgetting their hardships. Mr. Tanba confronts a violent drunk man in the street, disarming him with a few words simply illustrating the absurdity of his actions.

At dinner, Ryo seems to realize that his children don’t look much like him.

Into this mix, Kurosawa inserts a scene out of nowhere that takes on added weight in hindsight. Mr. So (Mashiko Tanimura) comes to Mr. Tanba in an effort to find help to commit suicide. Tanba gives So a tablet which is supposedly a deadly poison. But, after taking it, So contemplates his life, it’s high points and low points. So remembers his late wife and children. Tanba points out that So’s memories are the only thing keeping So’s wife and children alive in this world, which snaps him back to reality and he begs Tanba for an antidote. So doesn’t cry “madadayo” (not yet), but he could have.

Positioned in the center of the film, it encompasses many of the themes of the film. Reality, fantasy, life, death, and loves (lost or otherwise). Suicide has a tradition in Japan of being an acceptable end to life, but Kurosawa provides a strong argument against it. Considering events that would transpire after the film, it’s perhaps a question that Kurosawa was struggling with.

Kurosawa immediately goes from the lightness of this scene into one of the darkest scenes of his career. Katsuku again falls asleep in a bed of artificial flowers, a really beautiful image. Only, this time her Uncle isn’t sleeping off a bender, perhaps because he didn’t get his sake delivery, and gives into his impulses and rapes her. It’s a disturbing scene, all the more so because Kurosawa leaves the actual rape to the imagination.

This darkness continues with the Beggar and his Son. Their fantasy continues and the Beggar insists that they eat the fine fish they were given without cooking it. It’s the first statement of the dangers of fantasy.

Meanwhile, Mr. Hei ignores the return of Ocho, despite her obvious desire to reconnect and Kyota, drunk again this time in the local tavern, practically brags of his sexual conquests and waxes on about the sexuality of women.

It’s at this point that Kurosawa is moving into the end game with many of the stories. Ryo’s children have been hearing the rumors that he’s not their father and are upset about it. Ryo doesn’t tells them he has doubts, he only tells them that he loves them and that he’s their father and it doesn’t matter what anyone else says. It’s fantasy and truth all wrapped together. It’s a happy conclusion of issues for Ryo and his children.

Not so happy with the Beggar and his Son who find that they’re very sick from the bad fish they ate. Where one family found solace in fantasy, another is finding danger.

Katsuko’s uncle is finding his fantasy crumbling too, with Katsuko’s aunt returning. How long can he hide what he’s done when Katsuko is clearly traumatized?

Not all is darkness, though. The police bring in the thief that’s confessed to robbing Mr. Tanba. Mr. Tanba claims that he wasn’t robbed, to the surprise of everyone. And, in a sense, he’s right as he pointed the way to the money out of charity as much as anything. Again, Tanba uses fantasy to illustrate truth.

Shima is dealing with reality in his own way too. A few office friends stop by his modest home after work and his wife treats them rudely. They speak up about it, but Shima mounts a passionate defense of her. Of what she’s sacrificed to put up with him and his ridiculous tic. Perhaps he slightly romanticizes her sacrifices, but it’s also recognizing that they’re both imperfect people. Junzaburo Bani portrays Shima with complete dignity and really sells the character so that his sincerity is never in question. It’s a small part of the film, but it’s an entirely successful part, never verging into cloying sentimentality.

Kurosawa uses one husband and wife story to cut back to Hei and Ocho, again finding common thematic elements to serve as transition elements. In the night, Ocho, in a tear filled speech, pours her heart out to Hei in an effort to break through his shell. Ocho had an affair and was caught in the act by Hei and she now apologizes with all her heart and tries to explain to the best of her ability how it happened, pleading with him to come out of his zombie-like state and forgive her. Ocho’s mother didn’t forgive her before her death and she’s living with the regrets of her past sins and looking for a way forward.

It’s a long and affecting scene played with enormous emotion by Tomoko Naraoka. Kurosawa pulls a bit of a switcheroo. The story started out about the mystery of Hei, but it turned into Ocho’s story. Hei is hurt and has turned inward, but Ocho is the one that’s doing soul searching, not just dwelling on the past. She’s the one dealing with the reality of the situation. There’s no relief for Hei.

There’s no relief for Katsuku either, who finds out she’s pregnant from the rape. And she refuses to tell her Aunt about it out of shame.

Things aren’t looking better for the Beggar and his Son. Literally, as Kurosawa engages in his most theatrical visuals of the film, with extreme colors and makeup, to emphasize the toll food poisoning is having. I tend to think that the makeup crosses the line from theatrical into garish, honestly they’d be at home in a Romero zombie movie, but the images are striking and even if the aesthetic doesn’t always work, it communicates what Kurosawa wants it to.

Tanba tries to intervene to get the Beggar to take his son to the hospital but he’s stuck in the fantasy that everything will work out fine. Fantasy doesn’t help the Beggar deal with reality, it’s an escape. Tanba diagnoses this as weakness and fear, not pride, but it’s gravely concerning to all around.

Also gravely concerning is Katsuku’s pregnancy. Her aunt Otane and uncle Kyota debate what to do, with Kyota selfishly advocating for abortion. It doesn’t get them very far when the police show up to inform them of an assault involving Katsuku. The twist being that Katsuku wasn’t the one assaulted, but that she stabbed Okabe in a clear breakdown. Otane, of course, hurries off to see Katsuku while Kyota does nothing and seemingly has no concerns.

A lot of directors would not have resisted of the melodramatic flourish of showing Katsuku’s attack on Okabe. Perhaps it would have been the smart commercial decision in the context of the late 1960s / early 1970s. But, Kurosawa was very disciplined and the film remains of a piece, with a lot of restraint in approaching the material so that Kurosawa wasn’t exploiting the lower classes as much as exploring a group of characters that happened to be lower class.

And, as the Beggar’s Son worsens, the Beggar retreats into childish fantasy about the great house they’re building.

It’s at this point that Kurosawa turns his attention to wrapping up the remaining plot threads.

Despite attempts to shift the blame to Okabe, Kyota can feel the walls closing in with the police looking very closely for Katsuku’s motive.

Ocho at last reaches the point where she acknowledges that Hei is a lost soul and a lost cause. She compares him as a dead tree to a living one, still maintaining the shape but with none of the qualities. It’s a poetic statement which links to much of Kurosawa’s filmmaking which frequently featured shots of live trees, full of leaves and blossoms, swaying in the wind, and dispersing sunlight. She doesn’t achieve the forgiveness she sought, but she does find closure.

There’s a hint that Ocho’s leaving this time finally breaks through Hei’s shell.

Okabe lives. And Kyota flees when he’s told that Katsuku wants to talk to him in front of the police, confirming for everyone his guilt.

Comically, a drunk Masuo finds his way back to his original wife Tatsu, trusting on his colors to lead him to his rightful place. With help from Hatsu he finds his way back to his bed and Hatsu is sent packing back to Yoshie.

In a nod that everything is not going to have a happy ending, the Beggar’s Son dies. It prevents the film from being overly sentimental as it mixes tragedy, and the death of a child is a tragedy in any context, into the stories of the film. The image of the dead body is a real shock scene, worthy of a horror movie even.

Okabe and Katsuku reconcile and we find out why she stabbed him. It was suicidal thoughts misdirected. But, there’s promise that they’ll continue to see each other and Katsuku will finally have someone to love her instead of abusing her.

The Beggar buries his son and loses himself in his own fantasy as he has nothing to live for in reality.

Finally, Rokuchan pulls back into his “station” at the end of the day. There’s a suggestion of cycles which will continue on. We’ve reached resolutions of the current situations for certain characters, but life continues on and there are certainly more people living in the shanty town of the dump. And there are more fantasies to be envisioned. We end with Rokuchan’s fantasies as drawings on the wall, drawings made by Kurosawa himself. There’s certainly a suggestion that there are more fantasies to see, created by Kurosawa perhaps.

There almost weren’t more of these visions to see as Dodes’ka-den was a commercial failure, even with a small budget. It’s understandable as the film is restrained and the stakes are small. Despite the vivid colors, it was out of step with the big commercial hits of the time. It was well received critically, it was even nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, but it wasn’t the comeback that Kurosawa had hoped for. And, on December 22, 1971, Kurosawa attempted suicide by slashing his arms and throat. It was reportedly a quite serious attempt.

Kurosawa survived and in Japan with its tradition of ritual suicide, it was viewed without great scandal. But, his career appeared to be over once and for all. Surprisingly, forces beyond Japan stepped in to rescue Kurosawa’s career. Even more surprisingly it wasn’t the new Hollywood that was partially inspired by Kurosawa, it was the Soviets.

Next Time: DERSU UZALA (1975)