By 1950, the post-war occupation of Japan was running its course, and restrictions and censorship by the occupying authorities slackened. That was a good thing for the people of Japan as they moved towards a modern democracy. However, the rise of yellow journalism and the scandal sheet were not necessarily good things.

Kurosawa had some experience with the scandal sheets as he was once linked to actress Hideko Takamine in gossip magazines. Whether true or not, it evidently stung Kurosawa even though he never that thought much of the press. So, Scandal was Kurosawa’s protest against what he saw as a societal problem. A protest that Kurosawa felt strongly, perhaps too strongly.

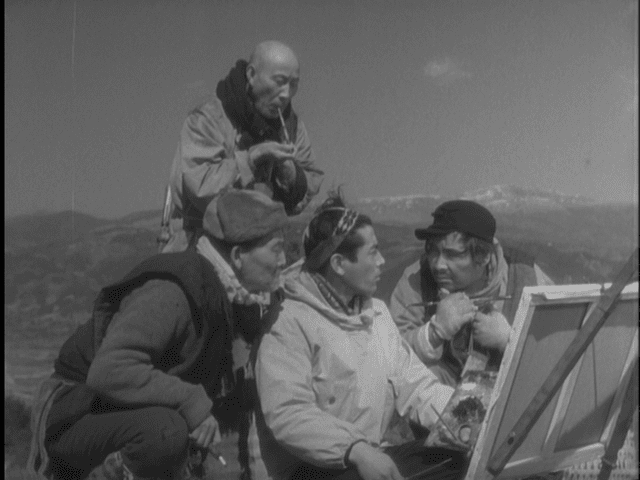

Scandal opens with our hero, Ichiro Aoe (Toshiro Mifune) creating a painting of a mountain before a group of interested, rural onlookers. It’s fairly easily to see Aoe as a stand-in for Kurosawa, a former painter himself, as he expounds on art and how he sees the world. Aoe’s mountain may be redder than what the locals see, but that’s how he sees it in his mind. In fact, the mountain may move which the locals can sort of see as they stare at the mountain. Kurosawa uses that occasion to frame these characters against the mountain in question to lead the viewer judge. It has nothing to do with the plot of the film, but it does establish character. Unfortunately, for a look at post-war Japan, the character of Aoe is a total romantic hero. He’s sensitive, principled, and this may be the best Toshiro Mifune ever looked on film.

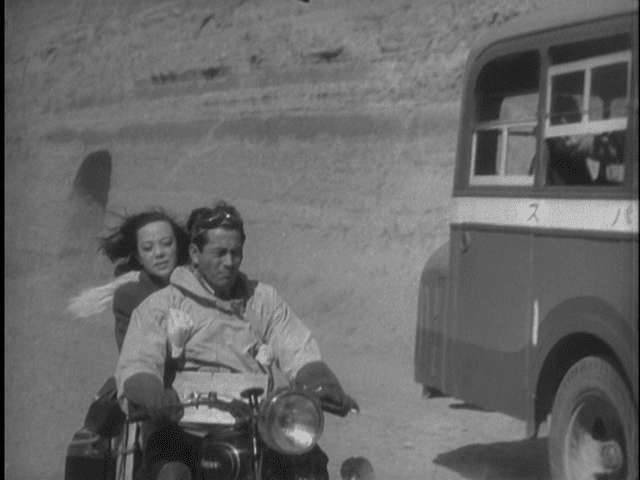

Aoe’s painting is interrupted by the arrival of Miyako Saijo (Yoshiko Yamaguchi). She’s a famous singer, and she enters the picture singing, on the vacation in the countryside. Unfortunately she’s missed the bus and it will be a long walk back to the inn. She’s too shy to ask, one gets the feeling that Kurosawa is implying that she’s a pure virgin damsel in distress, but the locals encourage Aoe to take her back on his motorcycle. So, the image is complete of the noble knight rescuing the maiden on his steed.

Along the way they pass a bus, complete with two paparazzi from the gossip magazine Amour who have been following Saijo. To them it looks like a story, whether or not there’s anything to it. When Aoe and Saijo have an innocent chat after cleaning up back at the hotel, with Aoe pointing out the local scenery, the paparazzi manage to snap a shot that looks like Aoe and Saijo are in a tender moment.

At this point, the photographers have a moment of doubt. What does the photo really prove? The editor, Asai (Shin’ichi Himori) blows off this sentiment. Asai notes that, for the most part, the famous blow off responding to the scandal sheets as beneath them. Perhaps because he’s not recognized, Asai is all the more eager to proceed with his rumor mongering. Soon, the story is everywhere.

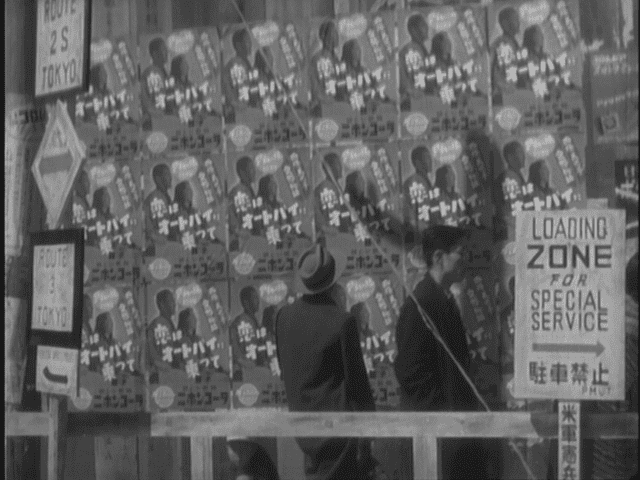

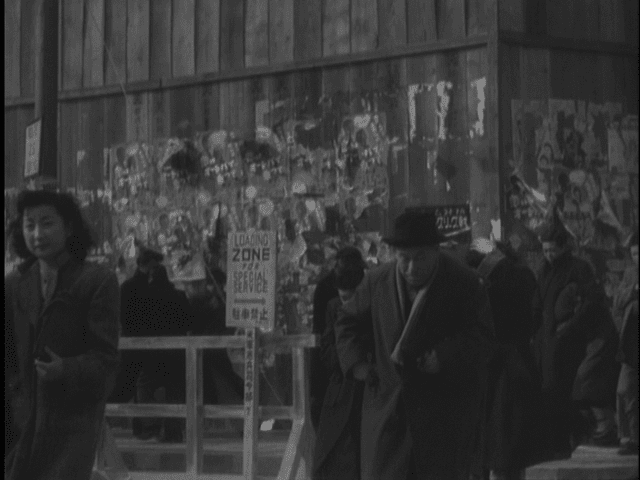

Kurosawa doesn’t delay the moment of discovery long though as Aoe ventures out of his studio clueless to the news, only to stop before the board of advertisements for his moment of discovery. Soon he arrives at the offices of Amour, his motorcycle announcing his arrival and responds with a punch to the editor. Soon a war of media words is on with Aoe threatening a lawsuit.

We check on Aoe in his studio at work with his regular model Sumie (Noriko Sengoku) as he contemplates going ahead with the lawsuit. Sengoku is a regular at this point after Drunken Angel, The Quiet Duel, and Stray Dog and does solid work as usual. There’s a thread of a subplot that’s introduced, Aoe is apparently smitten with Saijo, that’s never really followed up in the movie. But, it’s evident by Aoe no longer doing nudes and wanting to hold onto his mountain painting instead of selling it.

Whether or not our noble hero and heroine can win against the scumbag yellow journalists is the conflict that the film sets up. And, frankly, it’s setup in such black and white terms that there’s little drama left save for the trial. Compared to the scenario of something like Anatomy of a Murder with its very gray morality, Scandal is very weak dramatically at this point. Unlike The Verdict, the characters of the protagonists are beyond reproach so it’s only a matter of winning or losing, not redemption. Kurosawa had written himself into a corner and apparently he knew it as he struggled with the screenplay.

Kurosawa’s solution, rather than a page one rewrite, arrives in the film in the shape of Takashi Shimura as the lawyer Hiruta. Toshiro Mifune almost stole Drunken Angel from Shimura, but Shimura really does steal away and save Scandal. This being a Kurosawa film, Hiruta enters the film accompanied by a chill wind. Hiruta is evidently a lawyer of very modest means, but he makes a plea to represent Aoe and Saijo since he seems to truly believe in their cause. And to make money.

Aoe then makes a foolish, naïve decision and hires Hiruta. Sure, they show his research, but I’d advise everyone not to follow the Aoe method of selecting a lawyer. Aoe doesn’t check Hiruta’s references, he goes to visit Hiruta at his home, a home right by a cesspool out of Drunken Angel, and finds Hiruta gone but Hiruta’s daughter Masako (Yoko Katsuragi) is present. What Aoe finds is a very sweet girl who’s suffering from tuberculosis. Masako, with the winter/Christmas setting of the film, can very easily be called a Japanese stand-in for Tiny Tim. Aoe then goes to visit Hiruta’s rundown office and finds no evidence of Hiruta’s competency, but a picture of Hiruta’s daughter overlooking his desk. To Aoe, being a person of a good heart seems to count for more than things like competency, so Aoe selects Hiruta as his lawyer.

From a Kurosawa script, it boggles belief that one of his characters would behave in such a naïve manner. Having seemingly smart characters do stupid, illogical things is almost never a good choice in a movie and the whole second half of the movie rests on that single decision.

Fortunately, Hiruta livens up the proceedings. Hiruta goes to talk tough to Asai in the hopes of a quick settlement, but Asai quickly turns the tables on Hiruta. Before he knows it, Hiruta is borrowing money from Asai for gambling and taking a bribe to throw the case. Hiruta’s weaknesses make him interesting.

As does Hiruta’s conscience. Hiruta struggles with his weakness, hating himself for it, and that kind of legitimate drama is something that’s in short supply in the rest of the film. So as long as Shimura is on screen the movie is watchable and sometimes much more.

All of which leads up to the most memorable and manipulative part of the movie. Christmas at the Hiruta residence is kicked off by Aoe delivering a fully decked out Christmas tree on the back of his motorcycle. That’s not an image you see every day.

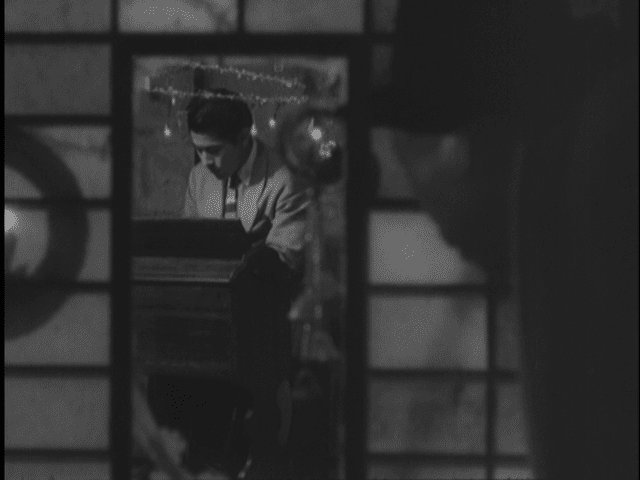

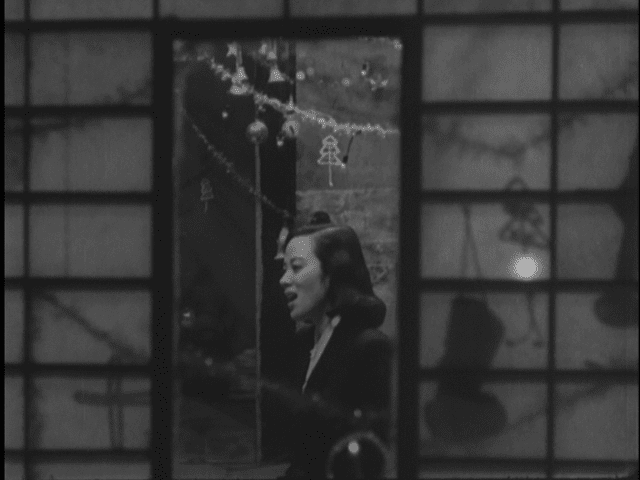

Hiruta’s out, but he arrives back to a carefully staged scene of Saijo singing “Silent Night” in Japanese, while Aoe plays an organ in the background (framed so that a halo is implied by the decorations), and Masako with her teddy bear framed like a little angel. Kurosawa selects a dolly shot down the hallway to show this scene in little snippets seen through windows as Hiruta drunkenly arrives home.

Hiruta flees, ashamed of himself, and Aoe follows. The sequence leads to a nearby bar where the patrons are drunkenly singing “Auld Lang Syne”. Hiruta joins in and resolves to be a better person in the new year. Given the time period, it’s certainly possible that this whole sequence is influenced by Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life although Capra might call Kurosawa to task for going overboard on sentimentality.

Kurosawa does cap off the whole sequence with an image that seems 100% his own. On returning to Hiruta’s residence they stop by the cesspool and see the stars reflected in the water. There’s beauty apparently in even the most humble object.

If there’s a better visual representation of Kurosawa’s ultimately hopeful view of the Japanese people being able to lift themselves out of the post-war hardships, I’m unaware of it. Kurosawa doesn’t linger long over this, there’s still a trial to proceed. And things don’t go well. Hiruta is in over his depth and has sabotaged the trial so that even when things go in his favor, the methods are called into question. Masako dies. And Asai sits there with a smug face knowing that Hiruta’s only chance of beating him is to destroy himself.

I won’t spoil the ending, but Kurosawa leaves the film on an ironic note as the last shots of the film show the tattered remains of the scandal advertisements. The characters put themselves through a trial over something that the general public ultimately will swiftly forget. It doesn’t mean that the damage wasn’t done, but that there’s very little monument to yellow journalism beyond the moment.

Scandal is very much the definition of lesser Kurosawa. There’s lots of craft on display, but the script is flawed. Kurosawa is so intent on getting his message out, worthy as it may have been, that he didn’t craft a film that was interesting dramatically, that had three dimensional, realistic characters, and that didn’t resort to blatant manipulation. No amount of fine camera work and terrific performances can be expected to cover up those problems. Unlike some of his earlier films where Kurosawa was dealing with outright censorship, he had no one but himself to blame for Scandal’s shortcomings.

I’m a third of a way through Kurosawa’s filmography and I’m going to take a two month break in order to build up my inventory. This is an appropriate point as Kurosawa’s career was about to radically change. With his next film, Kurosawa went from acclaimed Japanese director to international superstar and the most famous phase of his career began in earnest.

Next Time: RASHOMON (1950)