The Idiot didn’t do well, but after the international success of Rashomon it didn’t matter. Kurosawa had an unprecedented amount of clout for a Japanese director. However, he wasn’t quite satisfied that he had made his name with a period piece and explicitly said in his acceptance of the Venice Film Festival Prize that he wished it had been for a movie on contemporary Japan.

Given that wish, Kurosawa’s thoughts on mortality and purpose, and perhaps feeling a little guilty over how much of Takashi Shimura ended up on the cutting room floor, Ikiru emerged. There are no stories to tell about the making of the film, reportedly it was one of those films where everything came off without a hitch — in stark contrast to The Idiot.

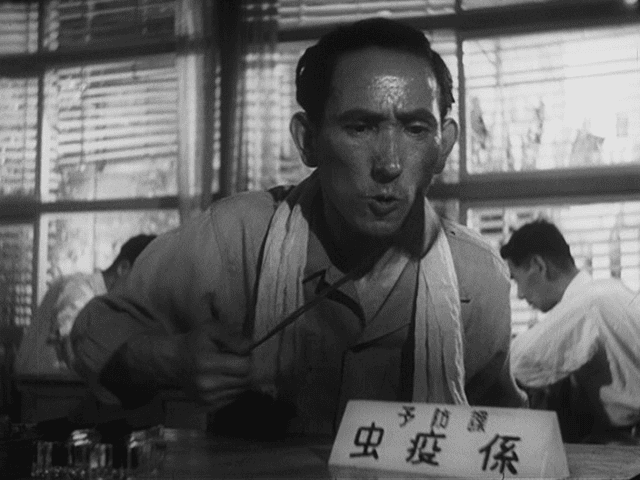

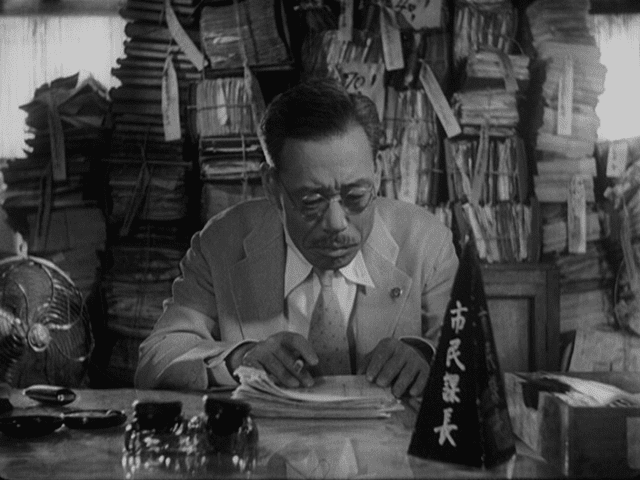

Ikiru translates literally as “to live” and the film wastes no time introducing the theme. The film opens on a shot of an x-ray with the announcement that the subject of the x-ray has no idea that he has a limited amount of time to live. We then get to see the subject of the x-ray, Watanabe (Takashi Shimura) diligently at work paper shuffling at his government job. The narration, which isn’t as somber and self serious as the subject matter would suggest, notes that Watanabe is hardly alive at present anyways.

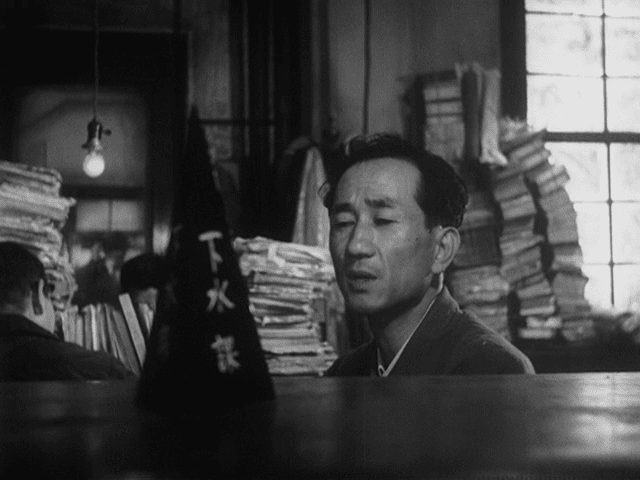

Kurosawa, unlike Ozu perhaps, isn’t content to dwell on Watanabe at present. The narration even notes that it would be tiresome to spend time with him now. Kurosawa was a filmmaker of action. After the female employee of the bureaucracy (Miki Odagiri) relates a funny joke about a worker who won’t take a vacation because he’s afraid he won’t be missed, Kurosawa quickly cuts away to a series of scenes of poor mothers who want a cesspool converted into a park. The women are given the runaround by the Tokyo bureaucracy who send them from department to department until they wind up back where they started. They berate the bureaucrats, but it gets them nowhere due to institutional indifference. While this is something that could be a throwaway, it’s also the seed to Watanabe’s redemption later.

After this world set up, the movie becomes downright intimate for a significant stretch. Watanabe doesn’t show up at the office one day, his first sick day ever. Instead we find Watanabe at the hospital where he’s about to hear the news about the x-ray that opened the movie. Kurosawa has fun with this sequence though as Watanabe never actually gets told the news by his doctor. First Watanabe runs into another patient at the hospital who gossips about a patient with stomach cancer, telling Watanabe what the symptoms of stomach cancer are and Watanabe’s growing recognition that those symptoms exactly describe his symptoms.

Then the gossip rambles on with how doctors never tell those suffering from stomach cancer that they have it and how little time they have left. Exactly describing the euphemisms doctors use to cover up the deadly diagnosis. It’s devastating to Watanabe when he hears those same euphemisms and can’t get the doctor to level with him.

It’s, of course, very good work by Takashi Shimura. More than that, the sequence is a lesson in how to sidestep clichés. We want to see Watanabe’s reaction to the news, but we don’t want to see the cliché of a doctor sitting at the desk flatly relaying the news. The doctor does indeed confirm the news to Watanabe across a desk, but the confirmation comes in the form of a denial and we’re already making leaps of logic just like the characters. The sequence serves to draw us in instead of just being served flatly to us. Moreover, it’s presented in an as exciting a manner as this type of material can be. Kurosawa uses deep focus cinematography a lot to create a significant depth of field and it makes the sequence visually dynamic. Heck, you can even see the opening x-ray in the background as Watanabe receives the news.

By this point, the movie itself has made a transition from the omniscient narrator to a much more personal and subjective point of view. Watanabe wanders out of the hospital in a daze and the soundtrack is dead silent. Until Watanabe almost steps into traffic when the sounds come blaring back to life reminding him and us that the world is still going on. Watanabe almost getting hit by moving vehicles is going to be a recurring motif of the film, reminding him, and us, that life can end suddenly and randomly regardless of our other problems. Every day could be our last day.

It’s at this point that we finally get a glimpse of Watanabe’s private life as we see his relationship with his son Mitsui (Nabuo Kaneko). Watanabe unfortunately overhears Mitsui and his wife planning on spending his money as he sits alone in the dark. There’s a gulf between father and son and Watanabe can’t bring himself to tell his son the news. Instead he returns to his room, to his prayers, and we’re treated to a terrific montage of Watanabe’s life. After the death of his wife, Watanabe dedicated himself nothing more to the betterment of his son, sacrificing his own life in the process, and yet circumstances, notably World War II, and his own lack of a life created a separation that can’t be bridged.

Watanabe stops going to the office, which leads to consternation both of his family and the workers in his office. And a terrific deep focus shot at the office depicting the astonishment of the bureaucrats at this turn of events. Although it’s not long before they start wondering who will take charge with Watanabe close to retirement.

With no respite in the past or with his family, Watanabe ventures out to drown his sorrows in drink. There he meets a novelist (Yunosuke Ito) and blurts out that he has cancer and not much time to live. Perhaps through misplaced pity, or perhaps because he senses a good story, the novelist takes Watanabe out for a night of debauchery on the town, to show Watanabe what it’s like to live and have a good time, at least in the novelist’s opinion.

What follows is one of the most acclaimed sequences of Kurosawa’s career as we’re treated to a look at contemporary Tokyo, particularly some of the more disreputable parts. The novelist’s idea of a good time involves drinking, dancing, strippers, whores, and all manner of sensation. All of those things are alien to Watanabe who manages to get his hat stolen in the tumult.

In the mid-point of this sequence they stop in a nightclub and when the piano player offers to play a song request, Watanabe asks for an old song, “Life is Brief”. Watanabe then sings along, in an old croaking voice, almost with a dirge, which brings everyone in the room down. Clearly this is a signpost that the revels they’re engaged in haven’t done much for his spirits. And it reminds everyone else that death is present.

The novelist redoubles his efforts at this point. But, ultimately it ends with Watanabe throwing up in an alley, presumably vomiting blood. The novelist has offered him sensation, which Kurosawa captures with filmmaking to match, but it’s ultimately no comfort. All that sensation passes and leaves a man tired and perhaps a little disgusted with himself, but no wiser and lacking fulfillment.

Watanabe’s return home the next morning is complicated by the office girl finding him on the street wanting approval of her resignation from the civil service. She finds the work dull because it doesn’t accomplish anything. She comes back to Watanabe’s place where he has his professional seal, fueling speculation among his son and daughter-in-law that he has a girl on the side, and they bond a bit over her nicknames for the rest of the staff and wanting to do something productive. Impulsively, after noting the holes and runs in her stockings, Watanabe decides to spend the day with her enjoying life and treating her to gifts like new stockings. Perhaps hoping her joy in life will rub off on him.

Although their relationship is viewed as something scandalous, at least by Watanabe’s son, daughter- in- law, and the workers at the office, the relationship is innocent enough from the viewer’s perspective. It’s a contrast to the debauchery of the night on the town, innocent things like going to a movie, having tea, ice skating. It’s perhaps Watanabe’s one respite. But it can’t last. The two have next to nothing in common, other than the girl perhaps likes the attention. Watanabe ends up begging for her to come out with him one last time at her job manufacturing toy rabbits. Interesting enough, her job is at a manufacturing plant making cheap windup toys, perhaps signaling Japan’s burgeoning reemergence as an industrial power. It hardly seems like a step up from a civil service position, but in the context of the times it’s a symbol of Japan producing something that’s wanted instead of merely shuffling papers around. The workplace is noisy and somewhat dirty, but it’s a symbol of Japan’s comeback.

Perhaps because he sees his last relationship slipping away, Watanabe confesses all. Watanabe likes her but wanted to learn to live, at least vicariously, through her. But, honestly, they have nothing in common.

Kurosawa uses deep focus as Watanabe and his erstwhile girlfriend have their last date. In the background of the scene, you can see the preparations of a birthday party play out and Watanabe’s girl watches women her own age prepare for a party while she’s stuck with Watanabe and all his problems. He asks what makes her so alive and her best response is that she’s now making things. And she suggests that Watanabe quit and do something else. Watanabe knows it’s too late for that, but it suddenly dawns on him what he can do. When Watanabe gets up with a renewed purpose the party participants break out in a round of singing “Happy Birthday” for their guest of honor. Kurosawa lays the seeds for this underlining of Watanabe’s breakthrough well. It doesn’t feel like simply underlining the theme but like getting the payoff for a good bit of background business that keeps the frame busy even when the main action is two people talking across a table.

“Happy Birthday” plays on the soundtrack again after Watanabe returns to the office with a renewed sense of vigor and decides that he’s going to push ahead and make a difference and get that park built. He says that before rushing out almost into traffic.

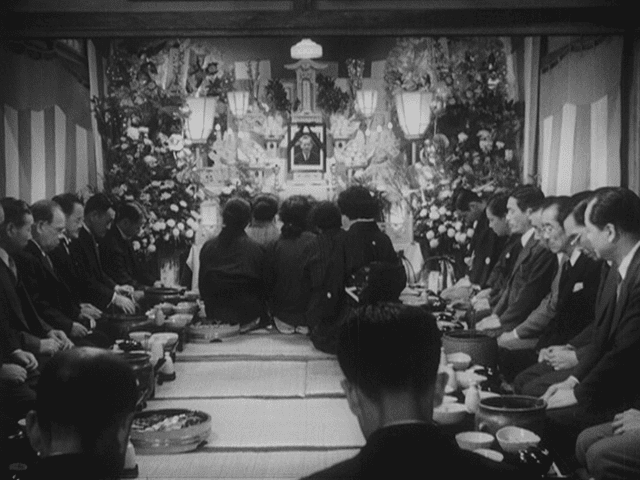

Then the film makes one of the most audacious cuts in film history, jumping ahead to the wake of Watanabe. The park is built, but we’ve no idea the first time we’ve seen the movie if the sense of purpose sustained him and gave him meaning he was looking for. Neither do his co-workers. The latter portion of the film is a puzzle to be worked out. It’s much like Citizen Kane, which Kurosawa is reported to have not seen at this point, with Watanabe’s actions late in life being told through flashbacks from multiple points of view.

It’s starts stately enough, but when the politicians and section chiefs leave the wake and the sake starts flowing, the movie really gets moving as the bureaucrats tell the story of Watanabe’s last days. The camera starts to move, the cuts are quicker, and we get to see Watanabe in action. He’s not transformed into a hero, he’s still the same old, stooped man who mumbles, but the difference is that he perseveres and won’t take no for an answer — whether it’s being a pest, begging, or standing up in the face of Yakuza toughs.

Watanabe’s park project represents Kurosawa’s awareness of the rebuilding of Japan. The cesspool was a symbol of Japan’s problems and neglect in Drunken Angel and Scandal. In Ikiru, Kurosawa literally buries the cesspool. Kurosawa wasn’t about to stop doing contemporary movies about the problems of Japan, but it’s clear that his sense of what Japan’s problems were was shifting.

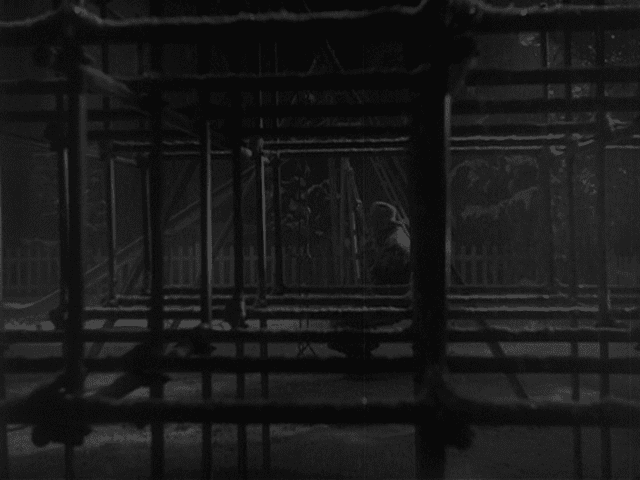

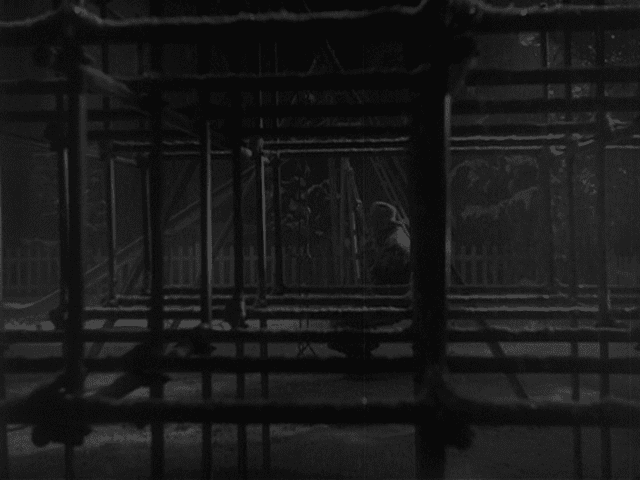

Watanabe’s arc ends with him sitting on a swing in the completed park, snow falling, while he sings “Life is Brief” again. Instead of being a dirge, it’s a song tinged with happiness. It’s undoubtedly one of Kurosawa’s most famous images and summarizes the beauty and hope that Kurosawa saw in life, even though he also knew it was difficult.

Of course, Ikiru doesn’t paint a totally rosy picture. Watanabe and his son don’t patch up their differences while he still lives. Watanabe’s office girl doesn’t come to his funeral. The politicians take all the credit for Watanabe getting the park built. And the bureaucracy goes on as usual at the office, despite drunken promises to change. But the park is built and the final shots of the film show a clerk, watching over it, perhaps being inspired. Watanabe made a difference in the end and some will learn the lesson and some will not.

Kurosawa was a director that liked to make statements and Ikiru is perhaps his finest statement on the potential of man to find meaning and overcome. It’s not necessarily that Watanabe’s solution of doing is the ultimate solution for everyone, but there’s hope that each individual can find something of lasting meaning. The world may be a dark place and the odds are against us, but if someone like Watanabe can find meaning and make a difference, then by extension we all can. It’s one of Kurosawa’s enduring masterpieces.

It’s also a knockout performance by Takashi Shimura. It’s all the more impressive to see him go from the bent, ill, sad Watanabe to Kambei, leader of men in his next Kurosawa film, a performance that couldn’t be further apart and is a wonderful display of Shimura’s range.

Ikiru was a popular and critical success, both in Japan and abroad, and is today seen, rightly, as one of Kurosawa’s greatest films. It’s the contemporary film masterpiece that he had been striving for since World War II ended. Perhaps having achieved that goal he decided on a new goal and set out to make a historic action epic on a scale he had never attempted before. The result is perhaps his most famous and acclaimed film.

Next Time: SEVEN SAMURAI (1954)