Akira Kurosawa conceived of updating Shakespeare’s Macbeth to Japan around the same time that he was making Rashomon. Kurosawa had been a fan of Shakespeare and Macbeth was his favorite play. Kurosawa was quoted as saying “I’ve always thought that the Japanes jidai (period) film is historically uninformed. Also it never uses modern film-making techniques.” Rashomon and Seven Samurai were his Kurosawa’s first cracks at that sentiment and in alternating between modern and period films in the 1950s he settled on Throne of Blood as his next project.

Throne of Blood was intended to be a modern film in many ways with concerns about modern Japan. Ambition merely for the sake of power and wealth was a pattern of behavior that concerned Kurosawa and he saw in the rise of post-war Japan many of those old lessons being forgotten. Kurosawa was also not interested in repeating himself. Rashomon and Seven Samurai are both period pictures, but strikingly different in approach. Throne of Blood would be completely different from them both.

One of the things that strikes a viewer right away is how much a departure Throne of Blood is from Kurosawa’s established style. The somewhat atonal music that plays over the credits sequence creates a spooky mood and seems more appropriate as an overture for Japanese theater than a Kurosawa film. Even after the credits are done, Kurosawa is in no hurry to get to the plot, we’re introduced to a barren, foggy landscape with a marker over the place of a former great castle, Spider Web’s Castle. A song warning of the lessons of the upcoming story plays over this landscape. The fog gets thicker, obscuring all view, and then the fog clears revealing a messenger running up to the gates of the restored castle. Kurosawa had been assiduously working in a style where realism was stressed over almost everything else since No Regrets for Our Youth. With a castle emerging out of a fog, as we recede into history, this is almost expressionism.

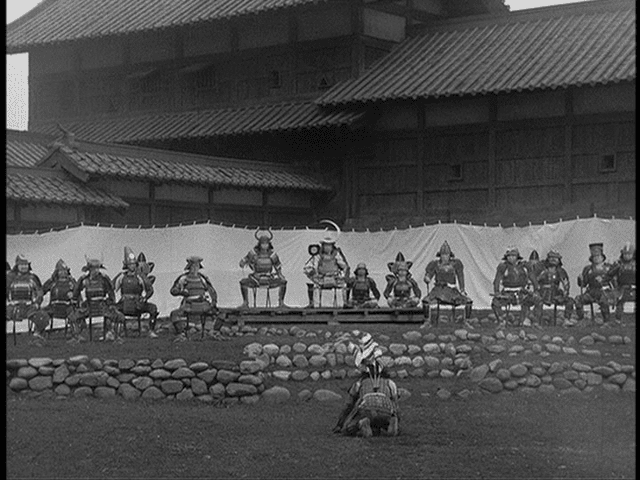

The messenger brings news of an attack on the realm to the Great Lord of the realm, seated high above with his counselors. Only the forces headed by Washizu (Toshiro Mifune) and Miki (Minoru Chiaki) stand between Spider Web’s Castle and the enemy forces and they’re outnumbered. While the setup is quickly established what’s really stunning is that Kurosawa reveals just what he intends to bring to this movie. The elaborate costumes and careful, still composition resembles nothing so much as Noh theater. Kurosawa isn’t attempting merely to transfer the setting of Macbeth from Scotland to Japan, he’s attempting to totally transform the whole play into a distinctly Japanese tradition.

Kurosawa uses messengers to imply a great battle is taking place off-screen, a very Shakespearian device. Without having to show anything more than the worry on the face of the Great Lord and his advisors, Kurosawa gets across the drama of a great battle. When all looks lost, the Great Lord’s chief general Noriyasu Odagura (Takashi Shimura) advises that they prepare for a siege and let the great Spider’s Web Forest confound their enemies. It’s at that point that news arrives that Washizu and Miki have secured victory against all odds and the movie segues into Shakespeare.

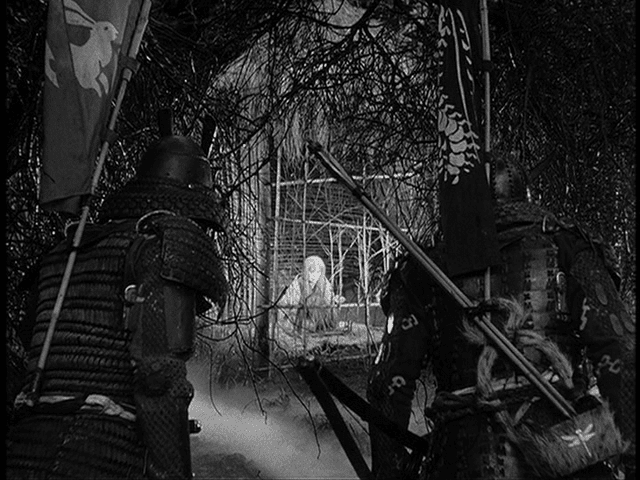

Washizu and Miki are summoned to Spider’s Web Castle and return through Spider’s Web Forest which even they find themselves going around in circles in. To Kurosawa’s great credit, the explanation of why it’s named Spider’s Web Forest is evident on the screen. Kurosawa often filmed his trees as beautiful, living creatures, swaying in the wind, and filtering sunlight. In Throne of Blood, the trees are still, often shrouded in fog, with their branches densely intertwined creating the very visual representation of a Spider’s Web. It’s a scary conception of a forest and works beautifully in the context of the film.

Although Kurosawa hasn’t been too busy with establishing the plot, he’s laid out the mise-en-scene of the film very firmly. This isn’t a film of sunlight and pleasant days. It’s a film of fog, tangled forests/webs, fog, rain, and wind. It’s one of Kurosawa’s darkest and coldest films and he’s preparing us for it right up front.

As in Macbeth, Washizu and Miki encounter a supernatural entity in the forest that provides them with a prophecy, of self fulfilling variety, that will lead to their destruction. Shakespeare’s rendition has a trio of witches. Kurosawa jettisons the western tradition and shows a distinctly Japanese spirit. The first appearance of the spirit has the spirit spinning thread, both a spider’s web and Washizu’s fate. It’s a purely Japanese conception and underscores how much Kurosawa has made the play his own movie instead of being trapped into a different tradition, a stark contrast to The Idiot.

The spirit foretells that Washizu will be promoted to Lord of the North Garrison and that Miki will be made commander of the Great Lord’s First Fortress that very night. Furthermore, the spirit foretells that ultimately Washizu will sit on the throne of Spider’s Web Castle and that Miki’s son will do the same. Since neither is the rightful heir to the throne, the implication is that they each would have to become traitors to the Great Lord. At which point the spirit vanishes in a great theatrical effect, seeming to vanish in a gust of wind, leaving Miki and Washizu among the bones of the victims of Spider’s Web Forest.

Kurosawa follows that up with Washizu and Miki galloping their horses to flee Spider’s Web Forest and its fog shrouded landscape. Obviously the implication is that they’re unsure of their way now, in more ways than one. Eventually they find their way to Spider’s Web Castle and at that point pause to consider their options. Kurosawa frames their conversation in deep focus with the fog shrouded Spider’s Web Castle looming over and between them. They lay their weapons down each pointing at each other. In many ways, the plot of the rest of the film is summarized in that single image. They can scarcely believe the prophecies and they quickly vow to keep the prophecies a secret, for fear of being branded ambitious traitors, but they want to believe the prophecies and are looking for proof that the spirit didn’t lie. A “proof” that is quickly provided when in a theatrical night time ceremony, perhaps a little reminiscent of Triumph of the Will which is perhaps Kurosawa drawing a parallel to Japan’s recent past as an ambitious world conqueror and fascist country, Washizu is promoted to Lord of the North Garrison and Miki is made commander of the First Fortress.

The film cuts forward in time to Washizu in power at the North Garrison and we meet the Lady Asaji Washizu (Isuzu Yamada) who is a striking presence. Heavily made up, she’s both a theatrical Noh representation of the Lady with perfect manners and a character that has one foot in the world of spirits. And she knows just how to play Lord Washizu, as she spins tales of how vulnerable he is if Miki were to speak about the prophecies and to prey on her own husband’s paranoia. In a playful bit from Kurosawa, a horse gallops in the background, displayed clear as day in deep focus, as a representation of Washizu’s emotions.

There are many terrific scenes in the movie, but this might just be the best. Isuzu Yamada is obviously conniving, but also unnerving and convincing. Toshiro Mifune gets to react, which he’s exceptionally good at, and make the counter-arguments, but even he can tell that he’s in a precarious circumstance. And the scene is punctuating with the Great Lord, with an armed procession, coming to visit unexpectedly. The explanation is that the Great Lord is going to launch a counter-attack, which is most certainly true, but coupled with Asaji’s arguments, there’s hardly a worse time and the audience even empathizes with Washizu’s paranoia.

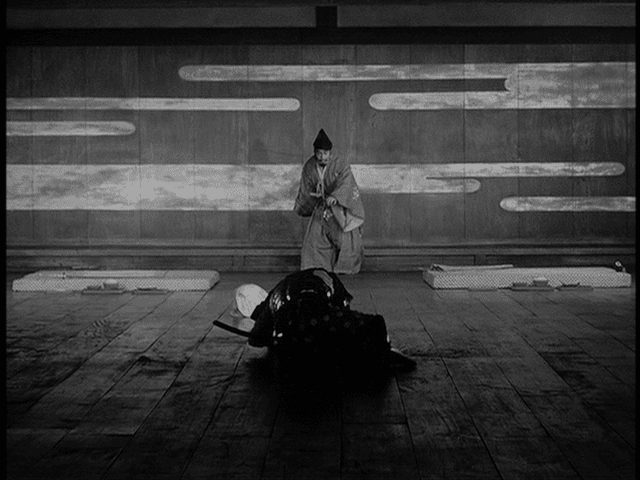

And, like Macbeth, the murder must be carried out. Not for any real reason, Washizu has no policies he wants to implement or grand visions, but simply out a sense of desperation and ambition. The whole sequence is unnerving, enhanced by Lady Asaji who moves about as gracefully as you would expect a woman of her position, with a slight swishing of her robes/slippers marking her movements. Even off screen you can hear that swishing which makes her appearance even more ghost like. Kurosawa is trying for maximum atmosphere leading up to the murder and he succeeds. The murder is off-screen, but you don’t need to see it as you can tell from Asaji’s reactions as her façade finally crumbles when her plans become frightening reality. Her horror continues right up to removing her husband’s spear from his tightly gripping hands and getting blood on her own hands.

The aftermath plays out pretty much the same as in Macbeth, but Kurosawa departs from Shakespeare by staging an extended horse chase as the Great Lord’s son along with Noriyashu flee to Spider’s Web Castle after being accused by Washizu of committing the murder. There’s no way for a horse chase to be envisioned in a satisfactory manner on stage and this is Kurosawa’s time to indulge in flawless action filmmaking. There’s added intrigue as Miki is now in charge of Spider’s Web Castle in the absence of the Great Lord and the question of whether he will offer sanctuary or side with Washizu is brought up. In the end, Miki welcomes neither the Great Lord’s son nor Washizu, driving off the son with arrows and locking the gates in front of Washizu. There’s theater to be played for the sake of the warriors inside the castle.

That theater is a great funeral procession as Washizu returns the Great Lord’s body to the castle. Kurosawa plays this sequence for all its worth. It’s a theatrical procession to be sure, an extended one at that, but Kurosawa also films it in a way that it showcases the scale of the production. They built a castle for Throne of Blood and Kurosawa makes sure it’s used to maximum effectiveness. Throne of Blood was not a cheap production and Kurosawa makes sure that the money shows up on screen.

Miki opens the gate, knowing full well the truth of the matter, and they both play their parts in fulfilling a prophecy. Washizu upholds his end of the bargain by naming Miki’s son heir to the throne. Much to the dismay of Lady Asaji, who throws a wrench into the works by declaring that she’s pregnant and Washizu is cutting off their own heir. Ambition must be followed, which results in Washizu ordering the assassination of Miki and his son. It’s only half successful as Miki’s son escapes, ensuring that Washizu has yet another enemy, and Miki’s ghost appears before Washizu at a dinner, with Washizu’s reaction ensuring that everyone knows the true nature of his rise to power. And, again, the ghost is a purely Japanese conception.

It’s the start of Washizu’s physical downfall. It’s punctuated by the first overt on-screen act of violence by Washizu as he murders the messenger reporting that Miki’s son escaped. Even Washizu seems horrified as to what he’s resorted to. This is futile violence since it doesn’t change anything except reflect that killing leads to killing.

The descent is rapid. Washizu’s child is stillborn, making the killing of Miki even more pointless. At this point, Washizu’s enemies decide to march on him and he seeks another prophecy from the forest spirit. The spirit informs him that he shall rule until Spider’s Web Forest itself marches on the Castle. Of course, anyone familiar with Macbeth knows what that means. What’s important is how Kurosawa films the sequence to bring it to life and he does a magnificent job of it. There’s pageantry of the assembled military forces, which serve as a precursor to Ran. There’s an ill omen of birds flying into the Castle while the assembled forces make mysterious preparations.

Finally the fog shrouded forest begins to move in one of Kurosawa’s most celebrated sequences. A sequence that isn’t done justice merely by showing stills of fog shrouded trees. It’s the almost dreamlike motion that makes the sequence special and must be quite spectacular on the big screen.

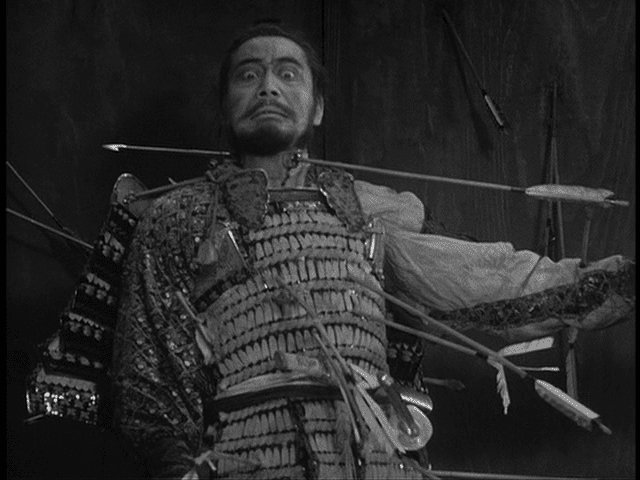

It’s at this point that Washizu’s men turn on him for their own skins. There’s no loyalty here. Nor does Washizu deserve any. There is perhaps a little empathy for Washizu as we see his fear up close. Kurosawa shows Washizu being attacked by swarms of arrows. The arrows miss Washizu narrowly, an effect achieved through the flattening effect of deep focus photography and skilled archers. Reportedly, it was still too close for Toshiro Mifune’s comfort and perhaps there’s no real acting going on by genuine fear. It’s undoubtedly effective and Kurosawa has one of the most audacious trick shots up his sleeve as Washizu’s life ends via an arrow to the neck. It’s a spectacular end to a spectacular film.

The ending of the film returns to the same fog shrouded place where the film started as the same song is heard. The ending suggests a cycle. History can and will repeat itself if you don’t learn the lessons. Throne of Blood is not meant merely as a pleasant entertainment but as a reminder of the dangers of ambition for its own sake. Murder begets murder. Betrayal begets betrayal.

Throne of Blood is a masterpiece and a reminder that even though a director may excel in one specific form, they can branch out and experiment with new ideas to great effect. The movie wasn’t a great box office success, something that must have disappointed Toho Studios considering they just signed Kurosawa to a three picture deal. But Throne of Blood was a critical success, especially outside of Japan where it was immediately hailed as one of the great adaptations of Shakespeare. Praise it still receives and deserves to this day.

Kurosawa turned his attention back to an adaptation of a play after Throne of Blood, only this time on a much smaller, more intimate scale. And, again, like The Idiot, with Russian source material, but this time determined to make it work with Toshiro Mifune as his centerpiece star.

Next Time: THE LOWER DEPTHS (1957)