Maxim Gorky wrote The Lower Depths in 1902, focusing on a group of Russia’s impoverished making do in a flophouse. With a theme of hard truth vs. comforting lies, it’s little wonder that it appealed to the director of Rashomon. Not that Kurosawa needed much encouragement in his fandom towards Russian literature.

Jean Renoir had done a version of The Lower Depths in 1936, right in the midst of a run of masterpieces, so Kurosawa had inspiration and competition. That apparently wasn’t on Kurosawa’s mind when he decided to make The Lower Depths because he thought it would be fun to film another play. Never mind that the play is often described as very dark and depressing, Kurosawa always found the individual characters interesting, and even funny to an extent, and that’s perhaps the key to interpreting the movie.

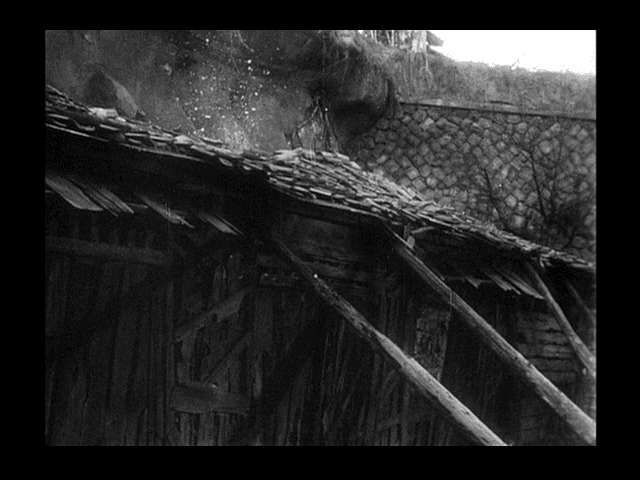

The film opens with Kurosawa doing a 360 degree pan while the title credits play as we look up to the walls of a confined ghetto. Kurosawa literalizes the setting of the film. Some peasants dump leaves into what they consider a garbage pit, and as the leaves fall we follow the leaves to the shack and courtyard that is the setting of the film.

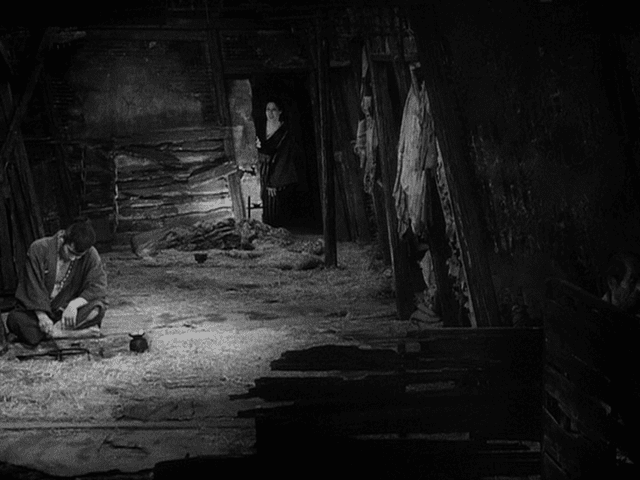

The setting is established and with a simple cut we’re introduced to the characters. And, as usual, Kurosawa uses the full frame and depth of field for his deep focus cinematography to pack the screen with information. Let’s look at a shot from the film.

In the background right, we have one of Kurosawa’s regulars Minoru Chiaki, most memorable for Heihachi in Seven Samurai, portraying a fallen ex-samurai, a character that may or may not be lying about his past to make the present more bearable. He’s not alone in that, in the mid-ground on the right is the prostitute Osen (Akemi Negishi) who also loses herself in her memory / dreams. A fact that the ex-samurai can’t stand, which is the pot calling the kettle black. In the mid-ground left is Otaki (Nijiko Kiyokawa), who isn’t so much a resident of this hovel but lives close by and is related to the landlady through marriage. She’s the only one that seems to have a career. Unlike the erstwhile tinker (Eijiro Tono), foreground left, who although he scrapes on a pot continually, seems to make no progress or have any real prospects. Perhaps he’s lying to himself about how destitute he really is. Kurosawa balances the staging so they’re all separated by some distance, which represents their position.

While this is obviously a limited set, it’s a well conceived one in many ways. All of the walls are different. There’s a doorway to a private room at the back which indicates that the resident is obviously of better means than the commoners in the main room. On the right there are a series of beds, many hidden by curtains, through which characters can enter or retreat from the scene. To the left are the doors to the outside, people can enter or exit and you can glimpse the weather through them. By changing the setup slightly or moving the camera, by panning or tracking, the backgrounds can change constantly to make the single set more cinematic.

Kurosawa understands that what’s not shown in the frame is as important as what is. In that frame above, you may notice the edge of a bed in the right foreground. In that bed is the tinker’s dying wife, Asa (Eiko Miyoshi) who announces her presence through a continual coughing / moaning. Kurosawa is implying that she has TB. By not including the tinker’s wife in the frame, Kurosawa has to track, pan, or change setup when he wants to show her.

That simple bit of staging forces the camera to be dynamic. Kurosawa doesn’t do a whole lot of cutting in the movie, but by not putting every single character and prop in a shot he keeps the camera searching for events beyond the edge. A character walking across the room and the camera panning creates a totally different composition in as natural a manner as possible. It’s a reminder that you don’t have to blow up a play to make it cinematic. Perhaps it can be seen as a precursor to the first half of High and Low where the setting is also confined.

Which is not suggesting that Kurosawa isn’t inventive in how he stages The Lower Depths. Consider, for instance, that Kurosawa introduces two characters in a vertical composition.

In the lower bunk, you have the gambler Yoshisaburo (Koji Mitsui). The gambler is probably the most cynical character in the whole film, and perhaps the most honest. When told that he’ll end up in Hell, he openly wonders how he can end up there when he’s already in Hell. When he’s caught cheating at gambling, he wonders what’s wrong with that. In the upper bunk, the actor (Kamatari Fujiwara) is a perpetually pickled sot. Fujiwara played Manzo in Seven Samurai and is part of a Kurosawa’s little repertory company of actors that’s perfectly appropriate for adapting a play like The Lower Depths. Fujiwara’s slurred line readings perhaps lose something in translation, but he’s one of the few characters that seems to change his lot.

The Lower Depths is a serious movie about the desperate lives of the downcast, but it’s not a dour movie as much of the petty squabbling, such as whose turn is it to clean up, has a comedic bent to it. These characters are so low, that there’s really no penalty to speaking their mind and there are verbal barbs at regular intervals.

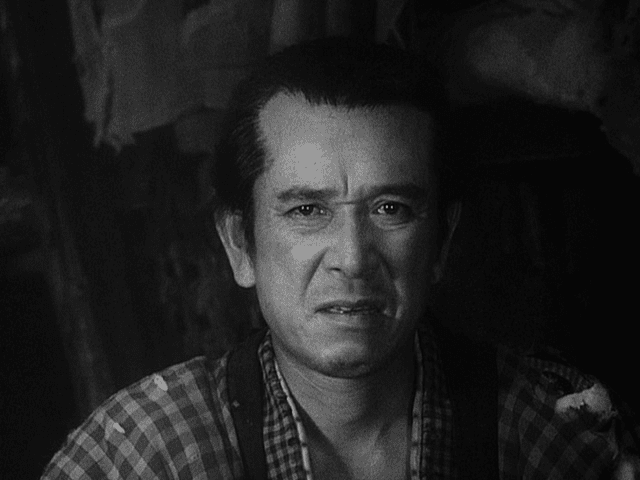

This comes out most when the landlord (Ganjiro Nakamura) comes sniffing around. Ostensibly to check on the conditions of his building, really because he suspects his wife Osugi (Isuzu Yamada) is sleeping with the thief Sutekichi (Toshiro Mifune). She is, but not at this time and anyways, the landlord is too mixed up in fencing Sutekichi’s stolen property that the question of who really is in charge and what anyone is going to do about it is relevant.

Sutekichi seems like the only person capable of picking up and moving on and up in the world of The Lower Depths. Even he is tied down by inertia. While he’s carrying on an affair with Osugi, it’s clear that he really bears a torch for her sister Okayo (Kyoko Kagawa), but won’t even say what his feelings are. Although those two seem to be the only ones unaware of the truth of the situation, which is a running theme throughout where others can see the truth much clearer than those involved. The fact that Osugi treats her sister Okayo in a cruel manner is a direct result from Sutekichi’s lack of commitment.

That’s roughly the status quo at the start of the film and it only needs an outside catalyst to get the plot, what there is of it anyways, moving. That push comes in the form of a traveling pilgrim (Bokuzen Hidari). Bokuzen Hidari had played Yohei in Seven Samurai and with his bald head, sing song speaking voice, and tendency to spout aphorisms he comes across almost as a proto-Yoda, at least in combination with Kambei from Seven Samurai. On the surface at least, because there’s more than a suggestion that the pilgrim is nothing of the sort, but almost a con man that tells everyone what they want to hear. Yet, he’s the only character that seems to come and go as he pleases, he never seems trapped by the surroundings that have overwhelmed everyone else. The rest of the characters talk about cleaning up the place, the pilgrim actually picks up a broom and starts cleaning, the fact that he’s the one character that escapes through action makes him more in line with the typical Kurosawa protagonist than all the other characters in the film, including Toshiro Mifune.

The pilgrim’s very presence seems to set what plot there is of the film in motion. The presence of Okayo in close proximity of Sutekichi when she leads the pilgrim into the room for rent, set’s off Osugi’s jealousy which leads to a burst of violence as Osugi beats Okayo.

Even in an outdoor action scene, there’s no scene where the characters are not shown confined to their circumstances. Kurosawa knows that and he uses the camera to place the audience in the same position. Walls are ever present in the film, which the deep focus cinematography helps make all the more apparent. It’s the last film Kurosawa filmed in deep focus, and Kurosawa uses it to full effect. Even more than that, Kurosawa keeps the camera on the same level as the characters and frequently lower. The vast majority of shots in the film are looking level or looking up, not looking down at the characters. Kurosawa is saying that we should identify with these characters with practically every shot.

The rest of the movie is really considering whether these characters can escape their circumstances or not, with the pilgrim making the biggest push that there’s more out there in the world. The pilgrim comforts the dying wife of the tinker by promising her there’s a better life in the next world. He encourages the actor to dry himself out, by promising him that there’s a temple out there that specializes in that. He encourages the ex-samurai and prostitute to indulge in their dreams/memories as an escape from their current circumstances. The only one that really isn’t buying it is the gambler, who accuses the pilgrim of resorting to white lies. Which the pilgrim doesn’t really deny.

Even Sutekichi gets roped in by the pilgrim. Osugi propositions Sutekichi to kill her husband, the landlord, and move in with her openly. It’s a testament to both Isuzu Yamada and Toshiro Mifune as actors that it plays out quite differently than in Throne of Blood. Isuzu Yamada was almost unearthly in Throne of Blood, here’s she’s quite human and quite fallible. Mifune and Yamada were larger than life and very theatrical in Throne of Blood, but in The Lower Depths they’re realistic, almost smaller-than-life characters. Watching The Lower Depths right after Throne of Blood is rewarding for that fact alone. Sutekichi, rightly, wants nothing to do with this plan, which is sure to fail. The pilgrim overhears the details and advises Sutekichi to run off with Okayo as anywhere else is liable to be better than current circumstances.

The murder proposition is the only real plotline in The Lower Depths. The rest is squabbling, some philosophizing, and the main characters not finding the will to leave their circumstances. It’s a testament to the script, with credit to Maxim Gorky for the story and Kurosawa for the adaptation, that the characters remain interesting and entertaining enough that the lack of a propulsive plot is never an issue. It’s also a testament to Kurosawa’s staging that the compositions on screen are always interesting. The Lower Depths is clearly based on a play, but many original movies don’t have as striking a composition as Kurosawa conjures up for a group conversation in a courtyard.

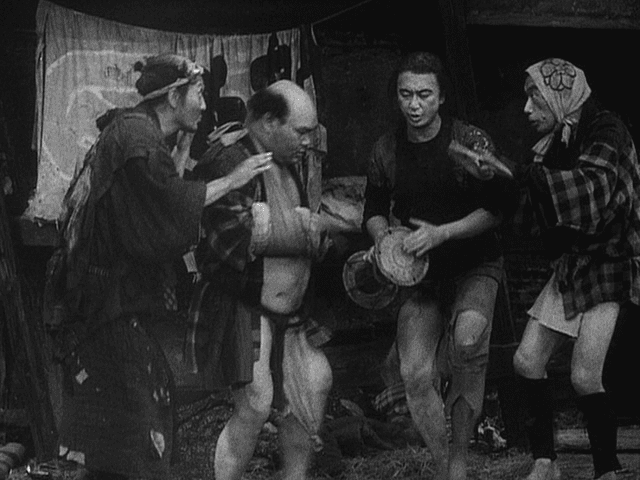

Sutekichi does make an overture to Okayo to run away that receives a mixed response. The actor tries to go sober. People try to change. But events overtake everyone and emotions boil over. Osugi goes too far in punishing Okayo, flinging a boiling kettle at her, and the result is a near riot. In that riot, Sutekichi and the landlord come to grips and in his anger Sutekichi shoves the landlord to the ground, accidentally killing him which brings an immediate stop to the violence as accusations fill the void.

The irony of the unplanned death of the landlord, signifies how little control these characters have over their fates. Sutekichi and Osugi are arrested, with the probable outcome being exile. Okayo doesn’t believe Sutekichi when he professes it was an accident, and refuses to run off with him. The result is a change of circumstance, but not at all how the characters envisioned it.

That goes for the tinker as well. His wife dies, but he has to sell his tools to pay for her funeral. The result is that he’s still stuck in poverty. The only one that gets away is the pilgrim. And that’s possibly because he was lying about his circumstances and beats a hasty retreat when the law arrives.

Yet, despite being stuck in these circumstances, it’s not all despair. There is a community of the downtrodden. A few drinks and the unfortunate are able to laugh, sing, and dance their troubles away. Life, even difficult life, isn’t all hardship and Kurosawa chooses to balance the positives with the negatives. The news of another, unexpected death brings the festivities to a stop. Even then, Kurosawa chooses to end the film on something of a punchline with the gambler looking directly into the camera, a successful breaking of the fourth wall unlike in One Wonderful Sunday, and complaining about the rotten timing rather than the tragedy of the situation. The film suddenly cuts to the end credits. It’s a bold, unexpected choice for the ending, dark and comic at the same time. The choice fairly accurately sums up the whole movie.

The Lower Depths did not perform well when released. No surprise that the audience might not have been willing to sit through a fairly bleak, albeit with a streak of black comedy, small scale movie without notable action. The Lower Depths didn’t get much in the way of positive critical response either, although the tide has turned on that. Toho had just signed Kurosawa to a three picture deal and the first two pictures, Throne of Blood and The Lower Depths, were certainly not what they were hoping for at the box office. Undoubtedly with much encouragement, Kurosawa returned to an action packed, lighter, samurai adventure film which had enormous influence the world over through its inspiration to George Lucas.

Next Time: THE HIDDEN FORTRESS (1958)