Kurosawa had signed a three picture deal with Toho Studios and Throne of Blood and The Lower Depths were box office disappointments, so for his third movie Kurosawa turned to more commercial grounds, a big, sweeping samurai film. But The Hidden Fortress bears little similarity to Seven Samurai, and even less to Throne of Blood and Rashomon. The Hidden Fortress is a loose, sprawling film instead of the tightly controlled earlier films and to top it off it’s the first film that Kurosawa shot in widescreen.

Of course, The Hidden Fortress is probably most famous in America for being the film that inspired George Lucas to make Star Wars. But there are myriad differences too and it’s shortchanging what George Lucas brought to the table and Kurosawa’s own film to call Star Wars any sort of remake. But, I’ll play along as the setup is similar. So, with a bit of artistic license…

It’s a time of civil war. The Yamana Clan has boldly attacked the Akizuki Clan and conquered their kingdom. But all is not lost as the Akizuki General Rokurota Makabe has rescued Princess Yuki and stashed her with 200 pieces of gold in a hidden fortress. But the Yamana clan will stop at nothing to find her. Meanwhile, two peasants have come to the war trying to make a fortune.

The film truly opens with Tahei (Minoru Chiaki), on the left above, and Matashichi (Kamatari Fujiwara) as a quarreling pair on the road. They had thought to make a lot of money selling weapons in the war, but they arrived too late and were mistaken for members of the losing Akizuki clan. Their quarreling is an obvious influence on C3P0 and R2D2, although neither has the prissiness of C3P0 or any pretensions of nobility. They’re in it for the money, not the heroism. Chiaki and Fujiwara were regular actors for Kurosawa. Chiaki played the priest in Rashomon, Heihachi in Seven Samurai, and the fallen samurai in The Lower Depths, among other roles. Fujiwara played the farmer Manzo in Seven Samurai and the actor in The Lower Depths. They’ve had important parts before, but had never been so central to the narrative as they are in The Hidden Fortress. Both carry their weight in The Hidden Fortress making two unlikely characters in a historic action drama memorable and relatable despite the fact that they’re the types that get forgotten to history and they don’t carry any of the action. They’re the heart of the film, flawed and venal as they are.

Ultimately the two just want to get home to the Hayakawa province. If they can make a little money along the way, great, but they’re already disillusioned. They’ve no idea of the adventure that they’re in for. It doesn’t take long though.

Tahei and Matashichi are interrupted by a fleeing soldier being chased by Yamana soldiers on horseback. The soldier on foot is brutally struck down before Tahei and Matashichi. It’s an early reminder of the stakes and how close death is. The black clad riders with banners will be a persistent reminder of the closeness of death throughout the picture.

Tahei and Matashichi aren’t worth the effort to the horse soldiers and the two soon break up to try to get back home by themselves. Both fail and wind up captured as slave labor. But, in the midst of their imprisonment, they find each other again. While their quarreling isn’t at an end, they’ll stick to each other through thick and thin for the rest of the picture.

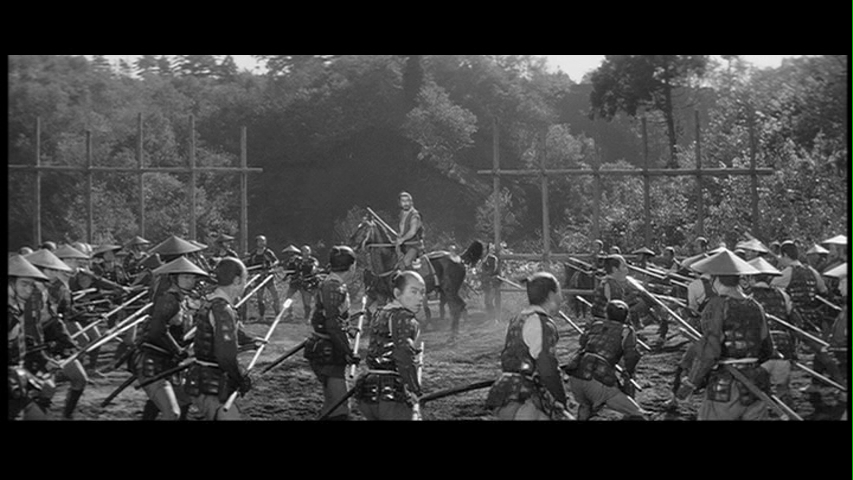

It would be a short picture if they didn’t escape. Frankly, the plot of the film could have started with the two already captured, but Kurosawa wanted to establish their relationship, their desperate straits, and the danger of the times. So, of course, they’re able to escape when the rest of the prisoners riot and attack the guards. It’s a grand cinematic gesture and ranks as one of Kurosawa’s biggest scenes ever. Punctuated, by our two protagonists fleeing into the wilderness (and stealing a pot of rice) instead of engaging in the spectacle.

Tahei and Matashichi make their way to the mountains, plotting how to get back home. And, by chance, they throw away a piece of firewood which makes a metallic ting. Investigating, they find that the piece of wood was hollow and contained a gold bar. All other considerations fade from view as they seek to discover the source of the gold and if there are more bars. At least until a mysterious and seemingly dangerous stranger (Toshiro Mifune) appears. At which point the pair retreat back to their camp.

They’re not rid of the mysterious stranger that easily as he appears at their campfire that evening. It’s at that point that Tahei and Matashichi unknowingly save their own lives as they explain how they plan to get to the Hayakawa province. Instead of heading directly to the Hayakawa / Akizuki border which is undoubtedly guarded by Yamana troops, they’ll instead head to the Yamana province first, the last place that Yamana troops would look for fleeing refugees and then make their way around the mountains to the Yamana / Hayakawa border which is undoubtedly not as well guarded. Akizuki province being represented on the map by a crescent moon and Hayakawa province by a series of three circles underline. This being Kurosawa, they illustrate this plan with a drawn map in the dirt. Mifune, still playing the mysterious stranger, recognizes the wisdom of this plan immediately, to his own amusement, and throws his hat into the ring by throwing a gold bar onto the map.

Mifune promises them that he knows where up to 200 bars of gold are and promises to split it three ways with them if they help him move it. And their own greed gets the better of Tahei and Matashichi as they struggle to move heaven and hell, climb impossible slopes, dig for no discernible reason, and do everything that they can for Mifune and the promise of a share of a great treasure. They end up doing the right thing for the wrong reasons and are a symbol of heroic scoundrels everywhere. Mifune leads them to a hidden Akizuki fortress in the mountains and immediately sets about keeping them distracted with meaningless tasks. And Mifune, who reveals himself as General Rokurota Makabe which is met by immediate disbelief by Tahei and Matashichi, and instead Mifune finds himself content to pass himself off as a common bandit, only interested in the gold, which is a motivation the two peasants can understand.

The presence of Mifune bends the narrative as he takes charge from Tahei and Matashichi. And, it’s not long before Princess Yuki (Misa Uehara) makes her presence known. But, when she does, the narrative takes a clear shape. Rokurota Makabe needs to smuggle the headstrong princess to the Hayakawa and all he really has at his disposal are the two peasants and a few horses. Disguising the princess herself is an undertaking in itself as she’s quite striking and there’s no disguising her voice and mannerisms.

And it’s not like Rokurota can trust Tahei and Matashichi with any secrets, the minute they do think they’ve identified Princess Yuki, Mataschichi runs off to town to claim the reward. Only to come back when he hears that Princess Yuki has been captured and executed, little knowing that Rokurota’s sister has taken her place and made the ultimate sacrifice to preserve the princess. A princess that seems like more trouble than she’s worth, to be honest.

A sentiment that even Princess Yuki shares when she hears the news of the sacrifice on her behalf. Who is she that someone should sacrifice for her? Is her soul any more worthy than the soul of Rokurota’s sister? Along with the peasants as central characters, it’s another example of Kurosawa subverting the typical period movie and questioning the basic tenets. It’s also the start of an arc for Princess Yuki as she must learn what type of ruler she should be to be worthy of other’s sacrifice.

It’s at that point that the journey, literal and figurative, can start. The enemy believes the princess is dead which certainly means a relaxing of the guard. There’s some fun reverse psychology business where Rokurota convinces Yuki that she must pass as a mute as she’d be instantly recognized otherwise. There’s a goodbye to some loyal retainers, including Takashi Shimura in a bit part, who again will sacrifice themselves to protect the princess. And then it’s goodbye to the hidden fortress and the start of the journey that will make up the remainder of the film.

Considering that the actual hidden fortress is only in about 20 minutes of the film, merely as a spot to set the plot in motion, the obvious question is does the title “The Hidden Fortress” have more than one meaning?

The first test is to get across a guarded river crossing into the nearest city. The discovery of the fortress which is burned to the ground ensures that they can’t turn back at the first obstacle. Tahei and Mataschichi try to run off with the gold at every opportunity and Rokurota has no Jedi mind tricks to play on the border guards, which makes the journey look impossible from the outset. But the sacrifice of a single gold bar, along with the mostly true story that he found it in the mountains, is enough for him to bluff his way through. Especially when he makes a scene when he doesn’t get his rightful reward and the officials and guards give him the bum’s rush to get him on his way. Kurosawa plays this scene for comedy including the fact that the officials are warned to be on the lookout for a man, a woman, and two peasants which follows almost immediately upon them gaining entrance and losing themselves in a city.

The first hurdle passed, Princess Yuki complicates things for Rokurota by insisting that he buy back one of her clan that has been sold as a slave and is destined for a life of prostitution. Rokurota reluctantly agrees, he is serving her after all. And that act of kindness appears to pay dividends as once on the road again, a patrol initially considers a group with two women of little concern.

However, the patrol comes back to investigate and Rokurota springs into action in one of the most exciting action sequences of Kurosawa’s, or anyone else’s, career. Rokurota kills the first two men, grabs his horse, and races off in pursuit of the two fleeing guards, cutting them down one by one as he gains on him. It’s thrilling filmmaking, clearly the inspiration of the speeder bike chase in Return of the Jedi and must have been an awe inspiring breakthrough in 1958.

The chase alone is a master class in filmmaking and many directors would have been happy to end it there. Not Kurosawa, who uses the momentum of sequence and some clever editing to show that as soon as Rokurota cuts down the last man, it’s too late to stop his horse as it barrels into a Yamana camp and he’s surrounded by soldiers in a composition that fills the whole frame. Not bad for a director who never used widescreen previously.

Surrounded, Rokurota finds himself at the mercy of Yamana commander Hyoe Takokoro (Susumo Fujita). Susumo Fujita was Kurosawa’s first leading man, and his return to working with Kurosawa, and opposite Mifune, is evidently something that Kurosawa felt needed a worthy showing. And Kurosawa delivers. Hyoe may be the enemy of the Akizuki clan, be he is also a man of honor and he accepts the challenge of a duel with the prize being Rokurota’s freedom. Coming on top of the great chase scene, it’s a cherry atop of one of the great action sequences of the 1950s. And, again maximizing the use of widescreen, they duel with spears.

Rokurota wins the duel by snapping Hyoe’s spear, giving Rokurota a reach advantage that would be impossible to overcome. But, instead of killing Hyoe, Rokurota spares him, another, in a chain of mercies. With that, Rokurota rides off to find the Princess and her not so loyal retainers.

It doesn’t do Rokurota much good as Tahei and Mataschichi naturally get them all in trouble. The duo think their being clever by joining in with a fire festival, with their load of wood, but the Yamana Clan is naturally looking for people trying to blend in. Rokurota arrives in time to help them escape the noose that they put around themselves, but dumping the wood with the gold in the fire and joining in the festivities. Festivities that just may have been on George Lucas’ mind for the Ewok village celebration at the end of Return of the Jedi. Meanwhile, Princess Yuki listens to the words of the Yamana song, dances the Yamana dance, and begins to understand what her enemies believe and sees them as plain people, rather than just the enemy. And, for the first time in the film, Princess Yuki smiles out of pure pleasure.

It’s a smile that will be short lived as they attempt to escape with the salvaged gold in the morning. Even some captured Yamana guards can’t help them escape quickly enough from the closing Yamana troops, who are given a truly ominous presence in the morning fog. Tahei and Mataschichi manage to escape, but Princess Yuki, Rokurota, and the female servant aren’t so lucky.

Captured by the Yamana, they await transport for execution in the morning. With Hyoe, evidently suffering the effects of being tortured for letting Rokurota escape, in charge of the transporting the prisoners and eventual execution. There’s no celebration on Hyoe’s part as he has the utmost respect for Rokurota. And Princess Yuki’s response is to sing the Yamana song, with understanding of how the common people live and knowing they only want to be treated with kindness and justice.

Ultimately, it’s the Princess who saves them all. Her kindness and understanding convinces Hyoe to turn on the cruel Yamana leadership and to lead a daring escape. The Princess didn’t protect herself by hiding inside a hidden fortress, but by living among the people and developing a sense of empathy and justice for those that serve. Her emerging good nature and the sense of her as a wise ruler is her fortress, hidden inside her all along.

Told in bravura fashion by Kurosawa, it’s a surprisingly gentle moral in a film filled with spectacular action and immense landscapes. The fact that the film turns on that lesson rather than force of arms is another way that Kurosawa takes the standard samurai formula and upends it in favor of something deeper.

Tahei and Mataschichi even get a reward of a single gold bar to split between them. Perhaps more than they deserve, perhaps not. Along with the bar comes a command from the Princess that they split it fairly, perhaps as a symbol of how good a ruler she will become the two argue over who will be more generous instead of their quarreling over who deserves a bigger share at the start of the movie. But all evidence is that they’ve changed for the better as well.

The Hidden Fortress was an enormous box office success in Japan, Kurosawa’s biggest to date and it ended his three picture deal with Toho on an up note and allowed him to form his own production company. And, of course, it inspired George Lucas. It’s perhaps a tad too long in getting the plot in motion, but it still remains an enormously entertaining film and an undoubted success for Kurosawa that stands the test of time.

After three films in a row that were a disappointment at the box office, the success of The Hidden Fortress gave Kurosawa the chance to turn to more contemporary concerns again. And this time, Kurosawa would deal with a Japan that had fully recovered economically and deal with his concerns of growing corruption as well as put his adoption of widescreen cinematography to a new milieu.

Next Time: THE BAD SLEEP WELL (1960)