Although Dersu Uzala was a hit in the Soviet Union and Europe, it didn’t do much to help Kurosawa get films made in Japan despite Kurosawa’s willingness to get back to work. Kurosawa was prepping three projects, Ran, a film based on Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death”, and Kagemusha. Japan proved to be a no go for financing as the Japanese film industry wasn’t interested in financing anything expensive if there was any question of it making its money back. The Soviets weren’t interested in films with subject matter that didn’t toe the government line. Kurosawa continued developing the projects, he personally illustrated every scene of Kagemusha over the course of several years, but he believed that Kagemusha was likelier to exist as a book of prints than as a realized movie.

And then Star Wars hit in 1977 and made George Lucas a person of true influence. Kurosawa came to America looking for financing and George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola were eager to help. They signed on as producers and convinced 20th Century Fox to invest in the international rights to the picture. With international financing in place, Toho Studios was convinced that they would make their money back and signed on for the rest and Kurosawa was back in business.Not that it was all smooth sailing, the film was delayed for quite some time because of a typhoon during production. On the first day of filming, Kurosawa had a falling out with his leading man Shintaro Katsu, star of the Zatoichi films, and they had to recast on the fly. Toshiro Mifune and Kurosawa would never completely reconcile and he eventually settled on Tatsuya Nakadai. There were other troubles during the shoot, but it’s the final picture that matters. And the final picture would prove to be a triumph.

The film opens on a six minute single shot featuring trick photography of the Lord Shingen (Tatsuya Nakadai), Shingen’s brother Nobukado (Tsutomu Yamazaki), and a common thief (Tatsuya Nakadai). They’re all dressed alike and bear a resemblance to each other. Nobukado has rescued the thief from the gallows because he recognized the uncanny resemblance to Lord Shingen and thought the thief would be even more effective as a double than Nobukado. The thief laughs at Nobukado and Lord Shingen for judging him, for he judges Shingen as a killer and thief of lands. Shingen accepts that he’s done some bad things, but justifies it by the fact that Shingen is trying to unite Japan and end the civil wars. There’s a higher principle at work than is immediately apparent which inspires Shingen. The existence of a higher principle/goal is part of the theme of the film.

It’s Kurosawa’s first prologue to a film and after a short credit sequence you can see that Kurosawa is clearly energized and engaged in the material. A messenger runs through courtyards of sleeping, brightly colored soldiers to deliver news on a castle Lord Shingen is attempting to siege The cutting is fast and edgy and the images are framed well with the bright colors really popping out of the screen. It’s a strong contrast to the first scene of the movie and quickly promises that there will be excitement and spectacle to go along with the sitting and talking drama.

The news is that the water to the castle under siege has been cut. There’s some hope that the castle will quickly surrender and some doubt because of the resilience of the defenders throughout the siege. The key symbol of the defiance being a flute played in the night. With the water cut off, Lord Shingen travels to the castle to hear if the flute still plays, knowing that its silence would signal that surrender is near.

That night, the flute does play, in a beautifully shot scene by Kurosawa full of color. And the beauty of the scene is interrupted by a gunshot.

Kurosawa plays coy. The news spreads but nobody knows for certain if Shingen is dead, gravely wounded, or just fine. Thereare two lords in particular that are greatly impacted – Nobunaga Odo (Daisuke Ryu) who almost mourns the dispatching of a worthy foe, and Ieyashu Tokugawa (Masayuki Yui) who practically rejoices in the rumor.

However, Shingen is not dead, but hastily forges peace terms and returns to his kingdom, with his double being used to project that he’s still alive and well. During this march Kurosawa indulges in filmmaking of an epic scale that he hadn’t really attempted since The Hidden Fortress. He even points the camera directly at the sun, further reassuring the audience that we’re in familiar and proven hands.

The epic imagery that Kurosawa uses further advances the story which is at least partially about the power of symbols and image. Which undoubtedly is part of what attracted Kurosawa to the story in the first place.

But, it’s Lord Shingen’s double that’s unhurt. Shingen has been seriously wounded and knows it. He knows that without him as a symbol the campaign for the Shogunate is doomed. He orders his generalsg them not to pursue the Shogunate if he dies. Further, to protect his clan, he orders that his death be kept secret for three years (with the knowledge that his reputation will protect the clan) and that no oneventures outside the clan territory. Nakadai as Shingen doesn’t project the fearful image that someone like Mifune would have to make that image truly palpable, but there’s never a doubt about his understanding of the power of image. And he knows that the image will protect his clan.

Shingen’s enemies have their doubts whether all is well with Shingen. There’s a long scene of a sniper demonstrating how he can target an object, such as a fancy chair for a lord, in the dark by establishing his aim in the day with the use of a plumb line and markers. Like always, Kurosawa is good at explaining things while drawing the audience in. Process is always fascinating to watch as well as people being good at their job. The result is inevitable but surprising. It’s entirely convincing process to Shingen’s foes, and it convinces the audience that Shingen’s foes have good reason to suspect. But still they doubt the process, which isn’t true proof, as the illusion of Shingen’s double is strong.

It’s an illusion that will prove key for the rest of the movie when Shingen dies from his wound. There’s despair that there will be no way to conceal the death for long, Nobukado unveils the thief to the council of Shingen’s generals and demonstrates his commitment to carry out the charade. This being a Kurosawa film, the winds of destiny howl at the brazenness of this plan. Nobukado is so brazen, that he doesn’t even inform the thief of the fact that the Lord is dead.

There are threats to this charade from without. A trio of spies, an everyman’s Greek chorus with strong nods to The Hidden Fortress, makes the case that all evidence points to Shingen being dead. There’s really no other conclusion that makes any sense. But seeing is believing and the uncanny resemblance of Shingen’s double makes them believe in Shingen’s health. But they’re not everywhere and miss the thief falling from the horse after leading the troops into a cheering state. But, it only takes one such failure in public to shatter the illusion.

And there are the threats to the charade from within. In a long sequence, the thief breaks open a large jar thinking there is treasure stashed within. Instead he comes face to face with the corpse of Lord Shingen. With the realization of how he is being used, his confidence shatters. Nobukado ultimately gives the thief the choice of continuing in the charade, they obviously can’t threaten the double with death and expect the charade to succeed, The thiefinitially refuses to continue the charade as he believes itb serves no purpose. The generals decide that they need someone willing to die for the Takeda Clan to have the commitment to pull off the masquerade and resolve to announce Shingen’s death after a burial in Lake Suwa.

But, while observing a spectacular burial sequence on Lake Suwa, the thief changes his mind as he overhears the spies and understands what it means to all the innocents of Shingen’s clan. All of Kurosawa’s strengths as a director are again in full flower, editing, cinematography, character, and theme as the thief comes to understand just what the symbol of Shingen means to the clan. The thief comes to understand the power of symbolism and the fact that he can save lives.

There’s no turning back afterwards, although there are complications. Kurosawa took his time setting up the film. Essentially Act One takes slightly over an hour, but it’s always a fascinating hour and sets many wheels spinning. The second hour kicks off with the thief publicly accepting his role at a Noh performance, which perfectly summarizes the style of the film with its pomp and ceremony.

Kurosawa doesn’t just settle for pomp and ceremony, he litters the film with little grace notes of humor and humanity. The Lord can’t just arrive to his home, the courtyard must be swept of all footprints with an uber-serious foremen making sure the job is done right. And the ceremony itself has perils. The thief’s first challenge is to publicly accept greetings from Lord Shingen’s grandson and heir. The young child blurts out right away that the thief is not his grandfather, but, after a tense few moments, including some improvisation by the thief, is persuaded otherwise. The masquerade will be challenged from unexpected directions, children being more perceptive in some ways than adults, and it’s a caution that nothing is to be taken for granted.

Nakadai is particularly good in this section. He technically breaks character at some points, glancing to see how the audience is reacting to his impersonation and being somewhat overwhelmed with everything around him, but willing to follow through with his performance even if he’s not entirely confident in its ultimate success.

It’s just the beginning of the challenges. There’s no time off for the thief and there are plenty of everyday challenges. Despite what you may have seen in the movies, stepping into another person’s shoes is not an easy task even if you do look like them. Managing the layout of a building that you may be unfamiliar with, for example. Remembering the names of people you have never met.

At this point, Nobukado steps in to mentor the thief and they form a bond. Certainly I don’t believe it’s any coincidence that their relationship bears a resemblance to a director with his lead actor. No doubt Kurosawa had a strong hand in writing the scenes between the two and it’s likely that the relationship between Kurosawa and Mifune is partly illustrated in the film.. Along with the fact that the thief doesn’t want to be a mere puppet but an actual contributer. Nobukado also bonds with the thief by empathizing with him as he knows how difficult it was to impersonate his brother, suppressing all of his individual identity.

Nevertheless, the show must go on. And steps are made to make the impersonation more effective. The thief is instructed not to try to ride Lord Shingen’s horse, as only Lord Shingen was able to do so. And, to the thief’s chagrin, he’s instructed not to utilize the services of Lord Shingen’s concubines as his lack of battle wounds is sure to give him away. The fact that the thief chafes at the latter instruction is a running source of humor. He even goes so far as to announce his impersonation to the concubines, only for them to treat it as a joke. Sometimes a guy can’t catch a break.

Shingen’s enemies are still not completely convinced and they decide to test whether Shingen is alive or not. They attack one of Shingen’s outposts to see the reaction. The plot development is exciting enough and Kurosawa shoots it in an expressionistic style full of color. It’s a much different style than Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood, or The Hidden Fortress and just as striking. It’s the full flowering of Kurosawa’s color experiments started with Dodes’ka-den. Kurosawa started as a painter and much of Kagemusha is painting brought alive.

The tests don’t come entirely from outside the clan as Shingen’s son Katsuyuri Takeda (Kenichi Hagiwara) chafes at not being in charge of the clan, his son is the official heir, although not of age, and his father’s shadow still looms over him. Katsuyuri wants to be a great lord in his own right and feels that his father never trusted him, skipping him over not just because he was the direct descendant of one of the clan’s enemies as well as Shingen. Kurosawa stages a great reveal of Lake Suwa, using a simple dolly and pan, where Shingen is buried in the background to remind us how Katsuyuri can’t escape from his father’s presence. Unlike in Dersu Uzala, the scenery doesn’t dominate the scene and character, but exists to enhance the message.

The thief is learning exactly what Shingen stood for in the meantime. He bonds with Shingen’s grandson, understanding what Shingen intended for him. The thief also learns the meaning of Shingen’s banner, representing the three parts of his army, horsemen, lancers, and more horsemen serving the lord. “Swift as the wind, Quiet as a forest, Fierce as fire, Immovable as a mountain”, with the army color coordinated to match. Shingen represents the mountain that forms the basis of the clan and his presence strikes fear in the enemy and confidence in the soldiers. The simple saying strikes the thief deeply and will be the basis for the final actions of the film.

The knowledge manifests itself immediately as the council of Shingen’s generals forms to decide what to do about the attack on one of their outposts. The public ceremony is supposed to be merely ceremony but Katsuyuri challenges the thief to reply to his requests in an effort to expose the charade, knowing that exposure would put Katsuyuri in charge. The thief surprises everyone who thinks the game is up, but replying simply that “the mountain does not move” to extend Shingen’s influence over the clan. This improvisation infuriates Katsuyuri and makes Nobukado a proud teacher.

But the thief’s public confidence doesn’t tell the whole story. Kurosawa engages in one of his purest flights of fancy, and his first pure dream sequence, in showing the theif being haunted by the ghost of Lord Shingen. Again, Kurosawa’s style has evolved to where his film looks like a living painting. There was a time when Kurosawa was a neo-realist, but in his age he turned from that into expressionism and it reveals a whole new side to him. Kurosawa may no longer have been physically young, but his boldness was undiminished.

There are more tests from without, including the use of Takashi Shimura in his last role in a small cameo come to assess whether it is Shingen or not, and being completely taken in the process, but the main battle is within the clan and within the thief. It becomes pronounced when Katsuyori takes matters into his own hands, for his own glory, to retake the castles taken by the enemy with his own men. The decision is made that Shingen’s army will support him, against Katsuyori’s wishes, and that the thief will have to be the unmovable mountain in battle.

The battle is one of Kurosawa’s great sustained sequences. And it’s played almost off screen for suspense rather than spectacle. We don’t know what’s going on, only that groups are battling somewhere out of sight. Shots ring out on occasion, striking down men all around the thief. Sometimes the trusted men who know his secret take a bullet that could have easily have hit him. Men are laying down their lives for the image of Shingen, embodied in the thief. The thief has his doubts, but holds his chair as the image of the immovable mountain.

The image works and turns back the enemy, who ultimately wanted to know if Shingen was alive or not. It’s a triumph of nerves for the thief, and it’s a triumph of Shingen’s reputation and image. It’s one of the great cinematic statements of the power of image.

Of course it can’t last.

Too impress Shingen’s grandson, and perhaps because he’s starting to believe that he is the embodiment of Shingen, the thief attempts to ride Shingen’s horse. The power of illusion only goes so far, it doesn’t apply to nature, and the thief is thrown. And, subsequently Shingen’s concubines examine the thief and see with his lack of scars he’s an impersonator. The power of the illusion is shattered and nobody in the compound believes any more.

The thief is dismissed quickly and with no thanks and he’s responsible for the disillusionment of the entire clan. He’s not even given the privilege of saying goodbye to Shingen’s grandson. He’s an exile without identity, neither as a thief or a Lord.

And there’s nothing to prevent Katsuyori from taking control of the clan. A lifetime of living in the shadows boils over and against every bit of advice, Katsuyori determines to march against the clan’s enemies for his own glory.

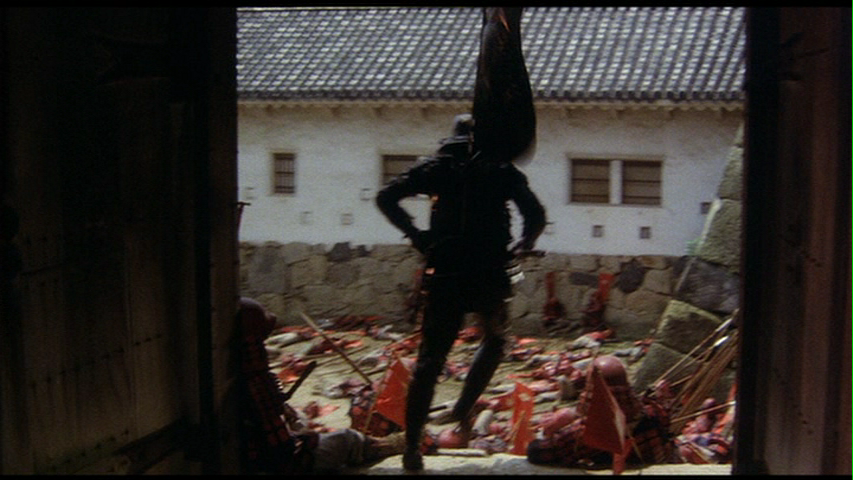

A glory that comes to a quick and bitter end. Kurosawa stages the final battle sequence by not really showing the battle, almost in a theatrical fashion. The thief has followed the clan into battle and sits between the two enemies. Katsuyuri orders his army to attack in waves and there’s recurring images. The Takeda clan’s army, first wind, then forest, then fire, charges. The enemy, behind a defensive line of fencing and barricades, fires their muskets. Katsuyuri and his generals look on in horror. And the thief looks on in horror too, becoming more and more like the ghost of Shingen with every drop of blood that’s shed. We see none of the slaughter, but we understand what’s happening all the same.

It’s not until the end when we see the last of the army charge that Kurosawa cuts to the aftermath and we see the devastation of the battle field and it’s a devastating image which Kurosawa dwells on for long minutes. Bodies litter the field. Horses dead and apparently wounded react in pain. As an image of the cost of war, this one waged for the foolishness of one man’s ego, it’s especially potent.

At this point, the thief, perhaps finally becoming Shingen, leaps forward to charge towards the enemy. It’s a futile charge of course, it’s not long before the thief is shot, but he fully becomes one with the Takeda clan and is destroyed along with the clan. A man that just wanted to save his own skin has had his identity consumed by an ideal. And he’s destroyed by it just as the clan is destroyed without that ideal to lead it.

The thief’s final actions are to try to raise the clan’s banner out of the river. Instead he’s swept away, to be forgotten by history. But, he’s also become Lord Shingen in many ways, even joining him in a watery grave.

Kagemusha is a full blown masterpiece and one of Kurosawa’s best films. It was a hit in Japan and a critical hit all over the world. In America it was nominated for two Oscars, Best Foreign Language Film and Best Art Direction, where Kurosawa’s film competed against, ironically, George Lucas’ The Empire Strikes Back. Now the question wasn’t if Kurosawa was going to make another film, but merely when.

It took a little time, but Kurosawa was going to prove that Kagemusha wasn’t a fluke or the last masterpiece left in him. Kurosawa had wanted to tackle King Lear for a while and he was finally going to get his chance, as an old man who had known hardship and failure.

It’s also where my life would finally intersect Kurosawa’s art and would change my life. It is also directly responsible for this series. But, more on that next time.

Next Time: RAN (1985)